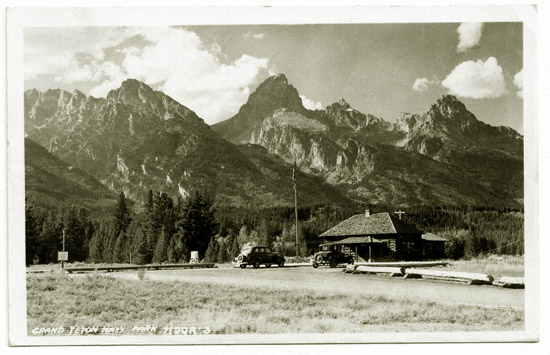

Teton National Park Headquarters, approx. 1936. In

background Grand Teton.

Grand Teton, as the highest of the Tetons, dominates the range. Just as the clouds coming from the west

oft obscure the peak, the mountain has been veiled in a dispute which has lasted more than 100 years. The

controversy centers on disputed claims as to who first scaled the peak.

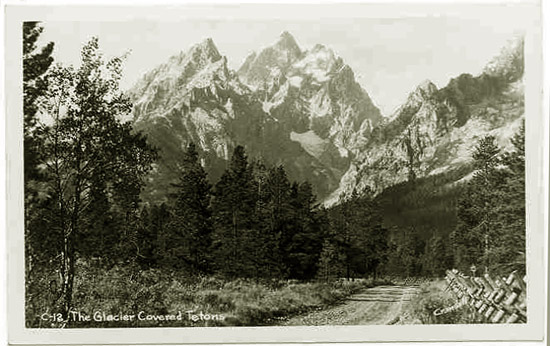

Grand Teton. Photo by Harrison "Hank" Crandall.

From 1872 until 1898, it was generally accepted that two members of Hayden's 1872 expedition, Nathaniel P. Langford (1832-1911)

and James Stevenson (1840-1888) had been the first to ascend the peak on July 29, 1872.

Stevenson had earlir participated in G. K. Warren's and W. F. Raynolds expeditions. Subsequently, he became of

managing director of the Geological Survey of the Territories and later served with the

Bureau of Ethnology in the American Southwest. Langford later became the first superintendent (unpaid) of Yellowstone

National Park. In June, 1873, an account of the climb was published in

Scribner's Magazine under the title The Ascent of Mount Hayden. The article was

accompanied by illustrations which sprang from the imagination of the magazine's artists. The effort by

Langford to rename the mountain after the expedition's leader was ultimately unsuccessful. The mountains were named by

early French-speaking trappers after portions of female anatomy. Langford failed to see the

resemblance of the mountains. The name is, perhaps,

more descriptive as viewed from the Idaho side where the mountains take on a gentler more rounded appearance.

In his diary, Langford described the ascent. On the climb, Langford and Stevenson were accompanied by

17 year-old Sidford Frederick Hamp (1855-1919) and 17 year-old Charles Langford Spencer (1855-1941).

Hamp was a nephew of William Blackmore, a prominent British investor who provided major funding for

the expedition including the equipment used by Wm. Henry Jackson. Spencer was Langford's nephew.

Langford wrote in his diary that upon reaching the upper saddle, Hamp

"though it best not to attempt to go

farther and as it was not decreed best to leave him alone on the narrow

bench we were then on, Mr. Spencer decided to remain with him, while Capt. S and the

writer made one more attempt to scale the rock confronting us. A rope which the

writer had brought with him proved of great service now, and throwing it over

a slight projection above our heads, the writer, supported and steadied as well as hoisted by

Capt. Stevenson below, drew himself up till he

could firmly plant his fingers in a crevice in the flat surface of the

rock; and then, with his feet supported by Capt. S's shoulder, clambered to the

top. Capt. S preferred to trust himself to his staff rather then the rope. I thrust one end

down to him, which he, with this aid,

grasped firmly and climbed to the top.

Here our progress again seemed effectually barred by a vast

field of ice overlying the smooth shelving rock, which rose at an angle of 70 to 75 degrees. Only at wide

intervals of space did this rock come in contract with this ice covering, and

a single misstep would have been instantly fatal, hurling

us thousands of feet down the jagged sides of the mountain.

Hestitating before abandoning the effort when so near the summit, and

hesitating alike to hazard our lives but encouraged by our two young

frineds at our feet, we made a final attempt to pass this

ice barrier. We were standing just at the point

of junction of the sheet of ice with the rocky side of the

mountain and laying fast hold upon the projecting points of rock upon the sides, we broke with

blows of our feet the edges of the ice for steps and thus rose slowly, step by step, till we passed the ice sheet,

a distance of 175 feet. From the top, looking down the

crevice between the iced and rocks, the sight, bringing forcibly to our

realization our peril had the ice sheet given way, was appalling.

From this point the surface was more broken and not more

difficult to ascent then below the ice, and, clambering over the

granite fragments, at 3 p.m., tired and hungry, after 9 hours of hard effort, we reached the

summitt * * *."

Franklin Spalding

Franklin Spalding

|

On August 11, 1898, a team under the

auspices of the Rocky Mountain Alpine Club and consisting of

the Reverend Franklin Spencer Spalding, (1865-1914) an Episcopal priest; William Octavius "Billy" Owen (1859-1947) an

engineer and surveyor; and Jackson Hole ranchers Frank L. Petersen (1860-1929)

and John S. "Jack" Shive (1862-1950) ascended the mountain. The Reverend Spalding had previously climbed a number of 14,000 ft. peaks in Colorado.

Previously, Owen had twice unsuccessfully attempted the climb of Grand Teton. Twice he was bested by the mountain.

The Reverend Spalding described the climb:

"Naturally, the north side of any large and supposedly

inaccessible peak is supposed to be the hardest climb.

But the Matterhorn is climbed most easily by the north

side, so was the Grand Teton. We decided to stick to

the north, and cautiously made our way along our gallery

until the man in front suddenly drew back with the

remark that it ended in a precipice that shot sheer down

for 3000 feet.

"Below the gallery and jutting out from the wall of rock

were two large slabs, probably six feet in length, which had

been sprung out from the main wall by the action of the ice

and rain. Behind those, after lowering ourselves to them,

we crawled along a distance of twenty feet, which brought

us to a little ledge under an overhanging rock. The ledge

was so narrow that we were forced to crawl on our stomachs.

"

The consciousness that a fall would land us 3000 feet

below gave us a decidedly creepy sensation. We had to

dig our fingers in the rough granite in places to pull ourselves

along. We encouraged each other by keeping up a

natural conversation, but it was with an inward feeling of

relief that we left the ledge and came to a sort of niche with

a small overhanging rock. Over this we threw a rope —

an action that required a cool and steady hand and a keen

eye. We pulled ourselves up and out over this 3000 feet

of space and continued up on the niche to about 50 feet.

It was so narrow that we had to use our feet, elbows and

knees. All of the rock was slippery and we could not go

too carefully. When we reached the top we went on another

gallery for a distance of nearly 200 feet to the west;

then up another ice niche, in which we were forced to cut

five steps. It was sixty feet high and led on to a ridge.

We followed a snow ridge for 200 feet, and then over the

sharp, jagged, eruptive rocks, so noticeable above the

timber-line, clambered with a shout to the top. We had

been climbing for eleven hours. It was a grand sight, one

of the grandest on earth." As quoted from the

Cheyenne Republican by John Howard Melish Franklin spenser Spalding,

Man and Bishop, The Macmillan Company, New Yok, 1917.

. . . .

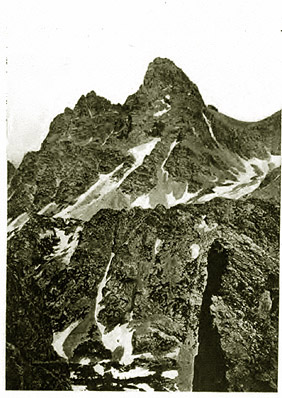

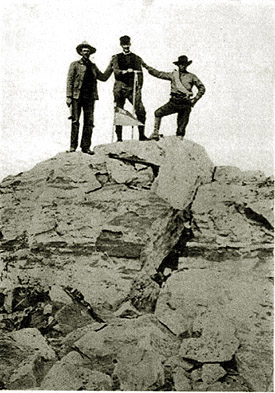

Left, Summit of Grand Teton;

Right, L to R. John S. Shive, Franklin S. Spalding, Frank L. Petersen. Photo by Wm. O. Owen.

Almost immediately, Owen embarked on a campaign denouncing Langford as a fraud. Letters were published

in George Bird Grinnell's Forest and Stream in which Owen referred to Langford as

a "pseudo-mountaineer" "a man, who by his own

confession, published by himself, has, by pulling on the end of a rope, ushered more men

into the presence of their maker than accompanied him in his alleged ascent of the

Tetons," a newspaper "mountaineer and mosquito finder," who could "manifestly manufacture lies much faster than

I have either time or inclination to refute," and as a "modern Munchausen."

Owen's argument that Langford failed to reach the top was based on the failure of Langford and

Stevenson to build a monument or leave a flag on the top, the absence of tin cans along the route,

Langford's account of finding mosquitos and mountain goat tracks near the top, and an affidavit from an

illiterate packer claiming that Stevenson and Langford failed to reach the top. The affidavit was apparently

authored by Owen himself. Langford duly noted of the affidavit,

"the voice is Jacob's voice, but the hands are the hands of

Esau." (Genesis 27: 22)

Owen wrote Grinnell that he would end the debate as one not worthy of the time. "It is," he wrote,

"a waste of lather to shave an ass." Notwithstanding Stevenson's death in 1888 and Langford's death in 1911,

Owen continued to get lathered up over the issue. It became almost an obsession that Langford's claim should be interred with him.

The boyish-looking, five-foot and slight of frame Billy Owen was not without political influence. He had served as the

State Auditor and thus was an ex offico member of many of the State's boards and Commissions. He took his campaign to the

Legislative Halls in Cheyenne. He secured legislative recognition of his claim that he was first. That, however,

was not good enough. In 1929, Owen finally drove the wooden stake into Langford's claim. As we all know, legislative

bodies have members who believe that they, and they alone, have a direct telegraph line to Ultimate

Truth. Federal congressmen, as an example, have the amazing ability to legislate, in addition to the laws of man, the laws

of physics and nature. Thus, in 1929, by Joint Resolution No. 3, the issue was decided once and for all. The Legislature

directed that a twenty-pound bronze plaque be installed at the very peak of Grand Teton. There, at dawn, the early morning

sunrise would be reflected off its gleaming surface to proclaim to all the world that Billy Owen was the first to ascend the

great peak.

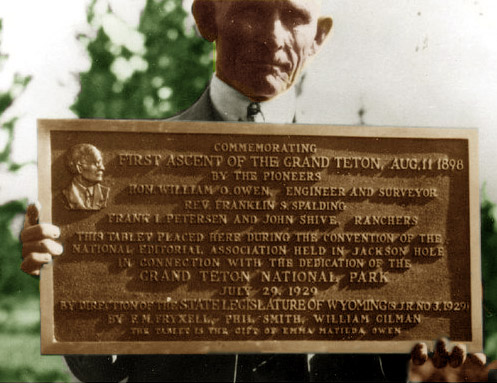

William O. Owen holding plaque, July 29, 1929.

COMMEMORATING

FIRST ASCENT OF THIS GRAND TETON, AUG. 11, 1898

BY THE PIONEERS

HON. WILLIAM O. OWEN, ENGINEER AND SURVEYOR

REV. FRANKLIN S. SPALDING

FRANK L. PETERSEN AND JOHN SHIVE, RANCHERS

THIS TABLET PLACED HERE DURING THE CONVENTION OF THE

NATIONAL EDITORIAL ASSOCIATION HELD IN JACKSON HOLE

IN CONNECTION WITH THE DEDICATION OF THE

GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK

JULY 29, 1929

BY DIRECTION OF THE STATE LEGISLATURE OF WYOMING, JR NO 3, 1929

BY F. M. FRYXELL, PHIL SMITH, WILLIAM GILMAN

THE TABLET IS THE GIFT OF EMMA MATILDA OWEN

The plaque, paid for by Owen and his wife, featured a profile bas relief of Owen. Notwithstanding that

the Reverend Spalding was first to the top, led the way on the final assualt, and actually tossed the rope which

assisted the others in completing the climb, Spalding got second billing. But then he had committed the

ultimate sin, he had supported the Stevenson and Langford claim. He had joined Stevenson and Langford in their ascent to a

Higher Place. At 9:00 p.m. on September 25, 1914, Spalding, then a missionary bishop, left his house to post a letter at a

mail box on South Temple Street, Salt Lake City. He was struck and killed by a speeding motor car driving on the wrong

side of the street. The last words of the letter about to be mailed, "* * * [N]ot a cloud in the

sky. Best love to all." His obituary in the New York Times made no mention of the climb of

Grand Teton. If controversy swirled about Spalding, it was his practice of preaching, in addition to the

Gospel According to Mark, the gospel according to Marx. He called it "Christian Socialism."

Thus it was that on July 29, 1929, the leading lights of Wyoming gathered at the foot of Grand Teton. Governor

Emerson, Wm. H. Jackson, Horace Albright, and Dr. Hebard were all there. Billy gave a speech. Frank Petersen and John Shive also came. The plaque, covered by

a flag loaned for the occasion by Dr. Hebard, was unveiled. Fritiof "Doc" Fryxell, Phil Smith, and William Gilman wrapped the

plaque in burlap and ascended the mountain for its installation. Apparently unheeded was that some unknown person with a

delicious sense of irony had arranged for the ceremony to be held on the anniversary of Stevenson and

Langford's climb.

Charles F. Kieffer

Charles F. Kieffer

|

But like Banquo's ghost, Langford's claim kept reappearing. First, following Owen's death evidence was found in his

own papers, that there had been an earlier climb on Sept. 10, 1893, by a young army assistant surgeon, 1st Lt. Charles F. Kieffer, and two other.

Dr. Kieffer was on temporary duty at Fort Yellowstone. Later, he served in Cuba, the Phillipines and at

Fort D. A. Russell. He is remembered today for his work on tropical diseases, the use of aspirin, and

study of truamatic injuries. The ultimate destruction of Owen's claim to have been first, however, occurred in 1968 when

diary of Sidford Hamp was found. Hamp was selected to particpate in the Hayden expedition over a number of other applicants including a nephew of

President Grant. On his way to Montana, Hamp's stage was robbed by two

road agents. After they had finished robbing the passengers, the road agents passed around a bottle of whiskey. Hamp confessed to

his mother that he took a swig because he was cold. Hamp wrote in his diary of the climb, “Spender

[Charles Spencer] and I stoped [sic] on a ledge and rested whilst the other two [Stevenson and Langford] got to the top.”

Thus, Langford's claim that he and Stevenson had climbed Grand Teton was vindicated.

The final death knell to the Owen claim occured in 1977. A person or persons unknown stole the

plaque. It has never been recovered or replaced.

Intriguingly, however, Langford, himself, suggested that

there were others before him. He based that on the presence a short distance below the

summit of the "Enclosure," a stone structure which appeared to be of great antiquity. Langford believed that it may be been

constructed by ancient Indians. Others have suggested that it may have been a former messenger for the

Hudson's Bay Company operating out of Fort Hall, Michaud LeClaire. Whether, Stevenson and Langford, the Spalding party,

ancient Indians, or LeClaire were the first matters, in the Grand Scheme of things, not. It was a tremendous feat.

As stated by Spalding in a letter to Langford, "Whether I was first or thousandth, the climb was worthwhile."

The mountain was not climbed after Spalding-Owen climb for another twenty-five years until 1923.

In short succession, it was climed on August 23 by a party of Quin Blackburn, David DeDeLap, and Andy DePirro from Montana, followed two days

later by a party led by Albert Russell Elingwood and Eleanor Davis. Davis, a well respected mountain climber and

physical education instructor, thus became the first woman to climb Grand Teton. A year later,

a local homesteader, Geraldine A. Lucas, age 59, made the climb becoming the second woman to ascent the peak.

Lucas (1866-1938) came to the Jackson Hole in 1912 from the Bronx where she had been a school teacher. She had two brothers who had already

settled in the Hole, Lee Lucas and Woods Lucas. Although born in Iowa, Lucas was reared in Nebraska and attended Oberlin College in Ohio.

Census information from New York indicates that she was a widow, although other sources indicate that she

had been divorced and legally changed her and her son Russell's name back to her maiden surname of Lucas.

In 1913, she had a small cabin contrcted at the base of Grand Teton. Bureau of Land Managemen records indicate that she

made a cash entry in 1914, proved up her homestead in 1922 and acquired additional property under the

Desert Land Act in 1927. Until her death in 1938, she remained a thorn in the side of the

Rockefeller interests then engaged in buying the valley, refusing all pressures to sell.

Geraldine Lucas Homestead, Jackson Hole, 1992. Library of Congress Photo.

The small cabin to the right was occuppied by Mrs. Lucas. The most distant cabin was constructed by

Mrs. Lucas for her son Russell. It was rarely used as Russell was in the Coast Guard and visited about

once a year. After Mrs. Lucas's death it was ultimately used as a summer home for an agent for the

Rockefellers.

Next page, Grand Tetons continued.

|