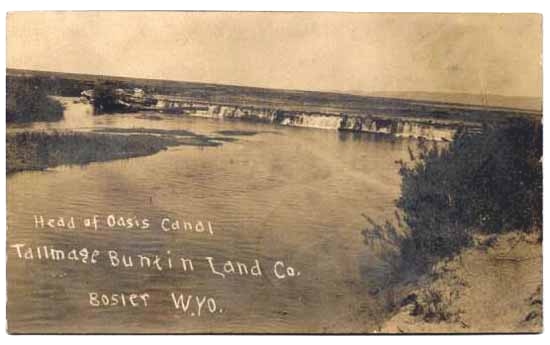

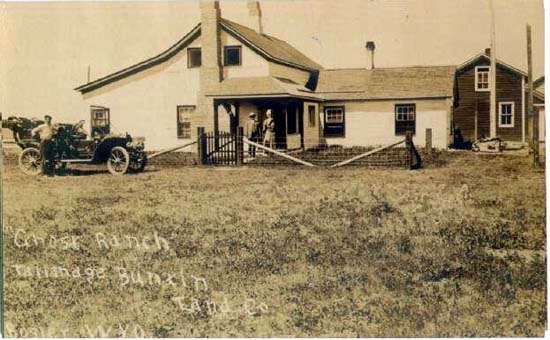

Promotional Postcard, Tallmadge & Buntin Land Co., Laramie

Valley Municipal Irrigation District.

With the passage of the Desert Land Act, otherwise known as the

Carey Act in 1894, devlopers throughout the state began the promotion of

large scale irrigation and land sale projects. The Carey Act was named after its

author, Wyoming Senator Joseph M. Carey. Many of today's cities such as Cody, Powell, and Wheatland are

as a result of those projects. In most instances, the projects might be deemed to have

been a success. The City's were founded, the settlers came, lots were sold and the

cities became prosperous. Almost uniformly, however, the private developers such as William

F. Cody, the developer of Cody, and the Wyoming Improvement Company, the developer of Wheatland

lost money. One project which was less than successful on all accounts was that of the

Tallmadge & Buntin Land Company and its attempts to develope the area around Bosler.

Laramie River and Irrigation Ditches, Tallmadge & Buntin Land Co., 1908.

The Carey Act provided that a million acres of federal land would be conveyed to

certain western states which could, in turn, convey 160 acre parcels to individuals upon the

completion of satisfactory irrigation which had been approved by the state engineer.

The cost of providing the irrigation would be assessable

against the parcels as a first lien. Thus, over time, private companies organized for the

purpose of constructing the irrigation systems would be reimbursed for the

cost of construction and the companies would then make money from the sale of the water. In order to

finance the construction, bonds secured by the assessments could be sold and the bonds

paid back from the moneys received from the assessments. Making money to pay

back the cost of providing the irrigation was dependent upon enough persons buying from

the state the 160 acres parcels at fifty cents an acre and agreeing to pay the

assessments.

Laramie Development Company Irrigation Ditch, approx. 1910

Irrigation in Albany County began in 1879 with the formation of the

Pioneer Canal Company. Commencing about 1908, The Tallmadge and Buntin Land Company controled by

Daniel C. Buntin of Nashville, Tennessee and E. R. Buntin of Chicago, began the promotion of small farms

which would be sold to potential farmers from the Midwest.

Financing was obtained from a

Nashville bank controlled by Buntin's father-in-law. Thus, success was dependent upon promotion of

applications for Carey Act lands. If insufficient land were sold, or if purchasers subsequently

defaulted, there would be inadequate cash to pay the bonds. The State assumed

no obligation to guarantee the bonds.

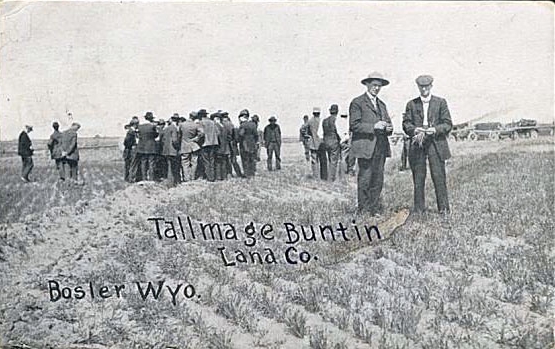

Tallmadge and Buntin Land Company promotional postcard, approx. 1908.

Note mispelling, "Tallmage." Tallmadge and Buntin's promotion promised bounteous crops produced through

irrigation. Promotional postcards were circulated throughout the midwest and excursion trains

brought in the potential buyers. Such promotions were no different than that carried out promoting

other parts of the state. Thus, as an example, the Eden Irrigation and Land Company

was formed in 1907 for the purpose of developing some 800,000 acres north of Rock Springs.

It advertised in national magazines:

A PUBLIC LAND OPENING----UNDER THE CAREY ACT----IRRIGATED LANDS----

----EDEN VALLEY, SOUTHERN WYOMING----

----150,000 ACRES----50 CENTS PER ACRE----

$20.00 DOWN HOLDS VALUABLE FARM IN DISTRICT NUMBER TWO. WATER ASSESSMENT

$30.00 PER ACRE PAYABLE IN 10 YEARS. IMMENSE IRRIGATION SYSTEM NOW BEING

COMPLETED. STATE FULLY PROTECTS YOUR INVESTMENT. WRITE TODAY ENCLOSING 4

CENTS IN STAMPS FOR PAMPHLET AND OFFICIAL MAP CONTAINING FULL PARTICULARS

AS TO FILING FOR JUNE OPENING. FILINGS MADE WITH OUT LEAVING HOME.

ROBERT LEMON, COMMISSIONER,

431 SCARRITT BLDG.,

KANSAS CITY, MO.

Other promotional material for Eden Valley compared climatic conditions as

approaching "hot house conditions to a remarkable degree."

The state, of course, did not fully protect the investment. Bonds used to

finance the project defaulted in 1927.

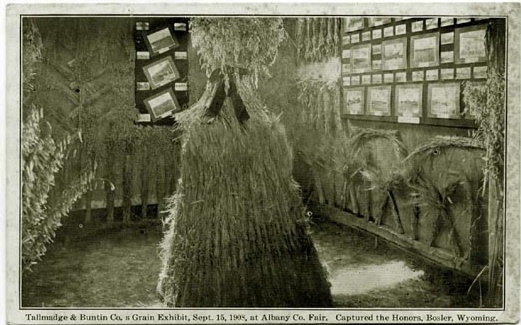

Promotional Postcard, displaying oat crop, Tallmadge and Buntin Co.

Buyers were promised that fortunes could be made from the farms. Thus, Professor

Larson noted that Tallmadge and Buntin excursionists came singing:

"The Excursion train came around the bend,

Goodby, my lover, goodbye.

All loaded down with Kansas men,

Goodby, my lover, goodbye.

We're going west to buy some land,

Goodby, my lover, goodbye.

They say they have water and don't need rain,

Goodby, my lover, goodbye.

They'll make all rich who ride this train,

We'll all buy land and settle down,

Goodby, my lover, goodbye"

Bosler 18 miles north of Laramie was promoted as a "banana belt." Considering Bosler's elevation of

7,080 feet above sea level, the claim might be regarded as somewhat exaggerated. In one instance,

disappointed settlers arrived in the midst of a raging blizzard. Skeptics, such as

the editor of the Lander Mountaineer, derided the claims suggesting that the

company might wish to plant figs, dates, and peanuts.

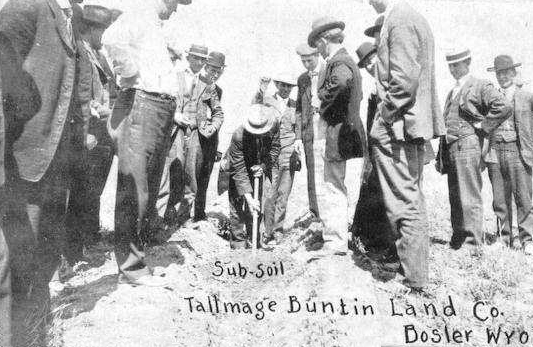

Promotional Postcard, Tallmadge and Buntin

Company

Prior to the Albany County projects, Buntin had made his reputation as the

developer of the "Arcade" in Nashville in

1902. The Arcade was a two-story enclosed shopping mall inspired by the Galleria Vittorio Emmanuele in Milan, Italy.

It is still in operation. Buntin's professional training, however, was as a lawyer, although he never practiced law.

Buntin was also involved in real estate for the Sante Fe Railroad near Amarillo. Previously Buntin and

E. R. Tallmadge were partners in the acquisition and sale of timber options in the Queen Charlotte Islands of

British Columbia. In 1909, allegations were made in several lawsuits in Illinois

that the Canadian acreage and timber cruises were fraudulently exaggerated.

Tallmadge and Buntin Land Company exhibit at Albany County Fair, 1908

In 1910 there was a drought. Buntin's company did not have a primary

allocation of water, but a secondary allocation of flood water which was to be

funnelled through Sodergreen Lake to a reservoir where it would be stored.

Thus, with the drought there was inadequate water for all of Buntin's projects. Few of the settlers brought in

by Tallmadge and Buntin remained.

Tallmadge and Buntin Land Company, approx. 1910

Buntin continued his interest in irrigation and in 1914 applied for permission to construct an

additional reservoir. Even with an extension of time, construction never

commenced. With $1,250,000 owed to his father-in-law's bank and a constant need to infuse

more money in the project for maintenance when moneys from the assessments were

short, Buntin must have felt like the man who went for a ride on the back of a tiger. About 1917, Buntin

moved from Chicago, where he was then living, to Laramie inorder to personally manage the situation.

In 1921, he failed to pay taxes due on some of his lands. Assessments for irrigation

were unpaid, indeed, some were owed as far back as 1905. In early 1922, Buntin returned to his family home in Nashville.

On Wednesday, January 18, 1922, shortly after 1:00 in the afternoon, Daniel Buntin, age 48, committed

suicide. His death was attributed to despondency over an "incurable malady."

But the tragedy did not end. Buntin's only son, Thomas, became increasingly despondent and

turned to alcohol. He was dependent upon his grandfather for his employment as the manager of an

insurance agency owned by the grandfather and upon his mother for a monthly allowance. He took out

two $25,000 term life insurance policies. Tom Buntin's problem was summed up by

Grafton Green of the Tennessee Supreme Court:

Young Buntin * * * knew how his father's life had been

ended and frequently talked about it, justifying his father's act.

It seems that the young man occupied the room in which his father had

committed suicide and that there was a hole in the wall made by the bullet

that killed his father. This hole was pointed out at times by young Buntin

to visitors in his home.

* * *[T]he young man talked to

others about committing suicide and ending his troubles. This talk,

while not taken seriously by some of the witnesses, seems to have

impressed others. Buntin's wife said that she woke up in the night on one

occasion, found him up in the room with a pistol in his hand, and took it

away from him after a struggle, during which the pistol was discharged.

Another witness noticed a pistol in Buntin's office when the latter was

talking about suicide and this witness made Buntin give him the pistol.

Dr. Burch, who was Buntin's friend as well as his physician, was

apprehensive that the young man would kill himself and took precautions

accordingly on at least one occasion.

On September 24, 1934, Tom Buntin left his wife with $1.50, got in his car at his usual time to proceed to his office

in Nashville. He dropped his car off for repairs. The car was never picked up.

As far as was known the younger Buntin had little money

with him. On September 26, Tom Buntin's uncle and grandfather each received mail from

St. Louis which contained a typewritten will signed by Tom Buntin. Shortly thereafter

it was discovered that the insurance agency was insolvent and in debt by

$70,000.00. Investigations in St. Louis failed to find any sign of Tom. Six weeks later

a stenographer formerly employed by Tom Buntin mysteriously disappeared. Even though

the stenographer had available some $37,000.00, no calls upon the funds were ever made.

A friend of Tom's, although not positive, thought he may have had seen young Buntin in the doorway of a hotel lobby in Lima, Peru.

The friend attempted to follow the man, but the man was lost in the street.

Further investigation in Lima found a taxi driver, a bartender, and a doorman each of whom allegedly recognized a photograph

of young Buntin as a person that each had served. Otherwise, the investigation proved fruitless. The insurance company upon which

the two policies had been issued spent upward to $100,000.00 investigating the disappearance of

young Tom Buntin without success.

After seven years in 1941, a Tennessee court determined that

Buntin, more likely than not, had committed suicide and that the disappearance of

the stenographer was coincidental.

Twelve years later and 19 years following the disappearance of Tom Buntin, a young investigative reporter for

The Nashville Tennessean solved the mystery. Tom Buntin was found in Beaumont, Texas, living under an assumed name and working as

a salesman. Thomas C. Buntin died in the 1960's still living under his assumed name. His mother,

the widow of Daniel C. Buntin, died in 1971 at age 93.

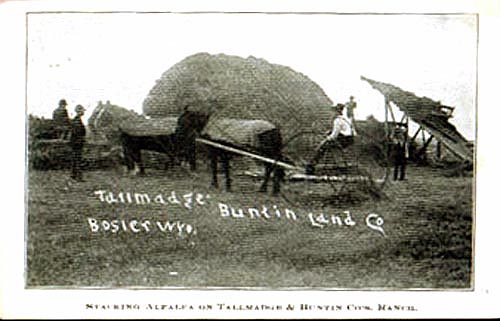

Stacking alfala harvest, Tallmadge and Buntin Land Co. Ranch, 1908

The device to the right of the alfalfa pile is a Mormon haystacker. In front of the stack is a hay rake. For more on

haystackers and hayrakes, see next page.

For more information as to Buntin see Laramie Rivers Co. v. Watson, 69 Wyo. 333, 241 P. 2d 1080 (1952);

Riedesel v. Towne, 66 Wyo. 160, 206 P. 2d 747 (1949); Caldwell v. Roach, 44 Wyo. 319,

12 P. 2d 376 (1932); New York Life Ins. Co. v. Nashville Trust Co.,

178 Tenn. 437, 159 S. W. 2d 2d 81 (1942); New York Life Ins. Co. v. Nashville Trust Co., 200 Tenn 513,

292 S.W. 2d 749 (1956).

It should not be taken that Wyoming was the only area in which there were failed agricultural projects. In New Mexico a B. H. Tallmadge

appeared upon the scene promising to bring prosperity to the area around Portales through irrigation. He ultimately

was indicted for fraud and departed the scene. In Colorado, B. H. Tallmadge began the promotion of irrigated

farm sites east of Pueblo and again disappeared. In Wisconsin in 1915, B. H. Tallmadge again appeared promoting

a drainage project which would make the area an onion capital. The promotion was carried out with

promotional post cards showing bounteous crops of onions, pamphlets, and excursion tours. Tallmadge again disappeared from

the scene with the project reverting back to a marsh. There are some indications that E. R. Tallmadge may have ended up in Canada.

Next page: dry farming.

|