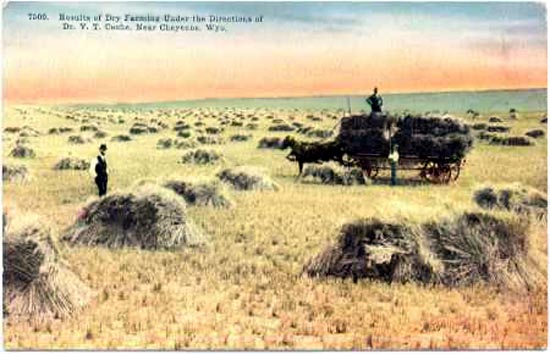

"Results of Dry Farming Under The Direction of Dr. V. T. Cooke, Near Cheyenne, Wyo.," 1906

And at the same time as developers were promoting irrigation, other efforts at bringing prosperity to

the state were made by the promise of agricultural development using

"dry farming." In 1906, John L. Cowan published his Dry Farming -- The Hope of the West, A Method of Producing Bountiful Crops Without

Irrigation in Semi-Arid Regions. Thus, Gov. B. B. Brooks chaired a Dry Farming Congress in Cheyenne in 1909. Notwithstanding, that

a snow storm reduced expected attendance, some 500 delegates were present. The following

year, another congress was held in Spokane under the chairmanship of Wyoming Congressman Frank

W. Mondell. Congressman Mondell had, himself, successfully utilized dry farming methods near Newcastle for five years.

Indeed, Professor of Botony and later president of the University of

Wyoming Aven Nelson joined the band wagon. In 1911, Dr. Nelson told an assemblage in

Cheyenne that with farming as the "backbone of our prosperity," the state might attain a population as much as

"two millions of people." There were some naysayers such as Bill Nye, publisher of Laramie Daily Boomerang, who earlier wrote,

Unless the yield this fall of most agates and prickly pears should be unusually large,

the agricultural export will be far below preceeding years, and

there may be actual suffering. I do not wish to discourage those who might

wish to come to this place but the soil is quite course, and the agriculturist,

before he can even begin with any prospect of sucess, must run his farm

through a stamp-mill in order to make it sufficiently mellow.

Dry Farming Exhibit, Wyoming State Fair, Douglas, 1908

Dry Farming Exhibit, Wyoming State Fair, Douglas, 1908

The historical premise for dry farming was explained by a Utah proponent Dr.

John A. Widstoe in his Dry-Farming, A System of Agriculture for Countries Under Low Rainfall, The

Macmillan Company, New York, 1920:

The great nations of antiquity lived and prospered in arid and semiarid

countries. In the more or less rainless regions of China, Mesopotamia,

Palestine, Egypt, Mexico, and Peru, the greatest cities and the mightiest

peoples flourished in ancient days. Of the great civilizations of history

only that of Europe has rooted in a humid climate. As Hilgard has suggested,

history teaches that a high civilization goes hand in hand with a soil that

thirsts for water. To-day, current events point to the arid and semiarid

regions as the chief dependence of our modern civilization.

In view of these facts it may be inferred that dry-farming is an ancient

practice. It is improbable that intelligent men and women could live in

Mesopotamia, for example, for thousands of years without discovering methods

whereby the fertile soils could be made to produce crops in a small degree

at least without irrigation. True, the low development of implements for

soil culture makes it fairly certain that dry-farming in those days was

practiced only with infinite labor and patience; and that the great ancient

nations found it much easier to construct great irrigation systems which

would make crops certain with a minimum of soil tillage, than so thoroughly

to till the soil with imperfect implements as to produce certain yields

without irrigation. Thus is explained the fact that the historians of

antiquity speak at length of the wonderful irrigation systems, but refer to

other forms of agriculture in a most casual manner. While the absence of

agricultural machinery makes it very doubtful whether dry-farming was

practiced extensively in olden days, yet there can be little doubt of the

high antiquity of the practice.

Kearney quotes Tunis as an example of the possible extent of dry-farming

in early historical days. Tunis is under an average rainfall of about nine

inches, and there are no evidences of irrigation having been practiced

there, yet at El Djem are the ruins of an amphitheater large enough to

accommodate sixty thousand persons, and in an area of one hundred square

miles there were fifteen towns and forty-five villages. The country,

therefore, must have been densely populated. In the seventh century,

according to the Roman records, there were two million five hundred

thousand acres of olive trees growing in Tunis and cultivated without

irrigation. That these stupendous groves yielded well is indicated by the

statement that, under the Caesar's Tunis was taxed three hundred thousand

gallons of olive oil annually. The production of oil was so great that from

one town it was piped to the nearest shipping port. This historical fact is

borne out by the present revival of olive culture in Tunis, mentioned in

Chapter XII.

Moreover, many of the primitive peoples of to-day, the Chinese, Hindus,

Mexicans, and the American Indians, are cultivating large areas of land by

dry-farm methods, often highly perfected, which have been developed

generations ago, and have been handed down to the present day. Martin

relates that the Tarahumari Indians of northern Chihuahua, who are among

the most thriving aboriginal tribes of northern Mexico, till the soil by

dry-farm methods and succeed in raising annually large quantities of corn

and other crops. A crop failure among them is very uncommon. The early

American explorers, especially the Catholic fathers, found occasional

tribes in various parts of America cultivating the soil successfully

without irrigation. All this points to the high antiquity of agriculture

without irrigation in arid and semiarid countries.

Dry Farming corn, near Laramie, 1906

The Agricultural Experiment Station confidently predicted that with dry farming one-fourth

the state could be profitably farmed on a regular basis and that half of the remainder of the state

could be profitably farmed without irrigation in a majority of seasons. Dry farming rested on the

premise that with deep plowing and harrowing of the soil after rain, that the

water would be stored for use of the crops. The problem, according to the "experts" such as

Dr. V. T. Cooke, was not lack of

rain, but with evaporation. Dr. Cooke was brought in from Oregon by Cheyenne businessmen to

promote the benefits of dry farming.

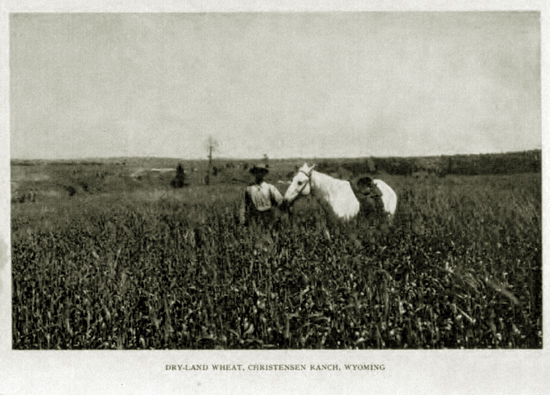

Dry Farming wheat Christensen Ranch, 1906.

The enthusiasm for dry farming was in partial reaction to a paper on the subject written by the

State Engineer Clarence J. Johnston. John L. Cowan explained:

[T]he members of the Young Men's Club of Cheyenne, Wyoming, listened to the

reading of a paper on the subject of dry farming by State Engineer Clarence J. Johnston. A project was at

once set on foot for the opening of a demonstration farm on waste lands near the city, supposed to be

entirely worthless without irrigation. The farm was put in charge of

Mr. F. C. Herman of the Irrigation and Drainage Bureau of the United States Department of

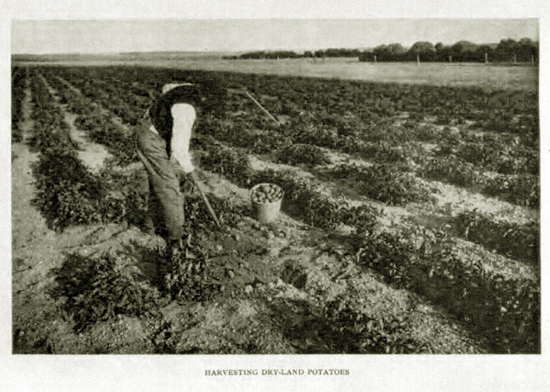

Agriculture. Last season record breaking crops of corn, otatoes, peas, oats, and garden

vegetables were grown on those "waste" lands. Winter wheat, rye, alfalfa, and barley were

also sown. Within ten days the grain was ten inches high, covering with a perfect carpet of green

the land that had been considered incapable of raising anything.

Dry Farming Potatoes, 1906.

With numerous books and magazine articles being written, publicity given by dry farming congresses,

reports from agrricultural experiment stations, and promotion by railroads, a wave of homesteading

spread across the northern plains, the Dakotas,

Montana, and Wyoming. The railroads, of course, needed a population to serve and were to a great

extent a real estate sales operation. Brochures were distributed across eastern Europe and the

immigrants came. In some areas, derision greated the new settlers. The 160 acres was, in many instances,

too small for effective dry farming. In some areas the new dryfarm settlers were called "honyockers,"

pronounced "hawnyawkers," drerived from the German huhn jäger, hen hunter, a chicken chaser.

In her 1912 novel, The Lady Doc, Cody writer Caroline Lockhart described the coming of the homesteaders to her

fictional town of "Crowheart":

They came in prairie schooners, travel-stained and

weary, their horses thin and jaded from the long,

heavy pull across the sandy trail of the sagebrush

desert. With funds barely sufficient for horse feed

and a few weeks' provisions, they came without definite

knowledge of conditions or plans. A rumor

had reached them back there in Minnesota or Iowa,

Nebraska or Missouri, of the opportunities in this new

country and, anyway, they wanted to move—where

was not a matter of great moment. Others came by

rail, all bearing the earmarks of straitened circumstances,

and few of them with any but the most

vague ideas as to what they had come for beyond the

universal expectation of getting rich, somehow, somewhere,

some time. They were poor alike, and the first

efforts of the head of each household were spent in

the construction of a place of shelter for himself and

family. The makeshifts of poverty were seldom if

ever the subject of ridicule or comment, for most

had a sympathetic understanding of the emergencies

which made them necessary. Kindness, helpfulness,

good-fellowship were in the air.

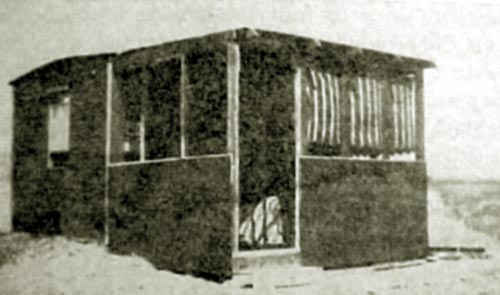

Dry Farm Cabin, 1912

As noted with regard to the Tallmadge and

Buntin Land Co. on the preceding page, a drought hit the state in 1910. A worse droght hit beginning about

1920 leading to the Dust Bowl. Dry Farming generally

needs a minimum of 15 inches of rain a year. Thus, the promotions of dry farming

turned to dust with the drought, and the state marked a substantial decline in

acreage devoted to dry farming. The impact of the end of dry farming may be illustrated by what transpired on the

Chugwater Flats and Iowa Flats on the plateau to the east of Chugwater. The two communities blended together with

Cugwater Flats being primarily in Platte County and Iowa Flats primarily in Goshen County. Beginning in 1911, Iowa Flats was also referred to as

"Iowa Center" becasue of the name after a post office was established in 1911.

Because of confidence in a change of climate that made dry farming

farming in such an area feasible, the area was opened to homesteading in 1908.

Iowa Flats Advertisement.

Beginning in 1909 many farmers from Iowa were attracted by glowing reports to Iowa Flats, so called as a result of the number

persons from Iowa who settled in the area. Foremost among them was former Iowa school teacher Robert A.Kletzing.

Mr. Kletzing published a pamphlet extolling the vitues of Iowa Flats. Additionally, glowing letters were published in various

Iowa newspapers.One such letter published in the Ottunwa Tri-Weekly Courier on September 2, 1911:

I am located on a homestead thirteen miles east of

Chug-Water and like it fine. We have a delightful climate.

Also excelent water which is reached at a depth of

100 feet. Out of the 365 days in the year, we have

330 days of sunshine. Our storms, while

severe, last only a few hours. The early return of the sun

soon dries the surface and thus we are bored but little with mud and dampness. In th summer

we enjoy cool breezes from the mountains which lessens the heat of

the day and makes the nights suitable for sleeping.

Land of Promise.

In connection with climate one thinks of

water. This part of Wyoming is blessed with an abundance of pure spring and

vein water. A year ago there were only fifteen shacks here,

now there are 375 familes with homes and improvements. Every one here

seems to be satisfied with the prospects.

Nearly all are breaking the prairie sod and planning for an early

planting in the spring. Those who put in crops early last sping had very good results depite a shortage of rain this past

summer. To show the faith settlers there have of the changes of this country, there

are three steam and gasoline engines and plows within a radius of eight miles.

Have church and School.

Sometimes lack of schools and churches are a drawback in a new country.

We are well provided with both here. There are but a few children that are not within three mils of a school house here. There is one

central church, a fine building and a salaried minister. In conjunction with this,

Sunday school is held in various places.

Leave Cattle Business.

There are many catle and sheep ranches here. One firm has been running

25,000 head of cattle and sheep on this range and are now shipping all of them and going into the sheep

business. The reason for this is because the homestead settlers are taking up the

range. this firm shipped 4,000 head from

Chug-Water Wednesday and Thursday of last week. The firm has now 100,000 head of sheep and are

planning to increase it to more than

200,000. A large number of antelope

about in this region and there are also many of the moaning but harmless coyotes.

I have 150+ acres and twenty acres broke at the cost of $3 per acre. School sections are selling from $13 to $17 per acre.

Potatoes are selling at $1.16 per 100 pounds. Nearly all of the settlers are from Iowa and the country around here is known as Iowa Flats.

Charles Bacon.

Kletzing in his promotional booklet so as to reasure the reader of plentiful water including a photograph of

Frank Marsh's property with what purportedly depicted a spring coming out of the side of a hill next to a spring house.

Purported Spring on Frank Marsh's property.

Although Kletzing referred to Marsh's property as being southeast of Iowa Flats, in the context in which given

it might be regarded as misleading. Marsh's land was in Meriden about 18 miles away and about 500 feet

lower in elevation. About the time of the book, Marsh lived at Wyncote, now a ghost town located near

Torrington. Nor was Frank Marsh a recent homesteader. He was a partner with Jess Yoder in the

Yoder-Marsh Cattle Co.

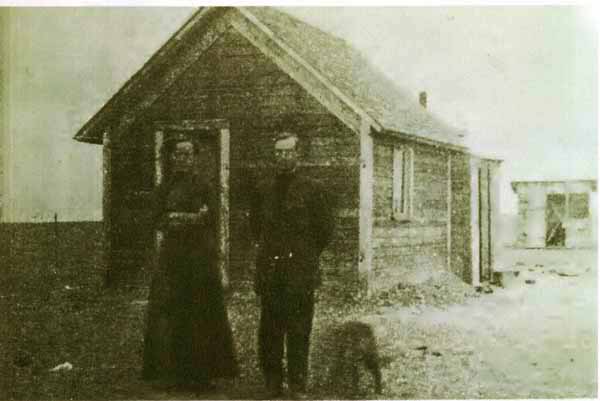

Charles and Belle Downing in front of homestead. Mrs. Downing also taught in the Iowa Center School.

The small cabin in the back was Downing's original homestead cabin. It was described in his "Recollections" as:

It was

"* * * a shack ten feet square with two windows. The

door, made from the extra lumber, faced south. The roof slanted

to the north and the floor was made of shiplap boards six inches

wide. There was no foundation, just runners on small pieces of

prairie stone; and it was unpainted. A drop side cot; a three-

legged, wood-burning stove; a table built from two-by-fours; and a

kerosene lamp completed the furnishings.

Music this page: Yodeling Slim Clark singing "Little Old Sod Shanty."

Next page: Iowa and Chugwater Flats continued.

|