|

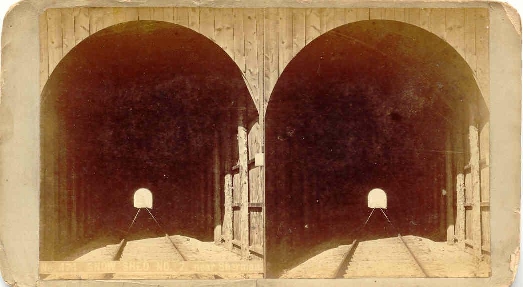

Snowshed, Sherman Hill, Stereograph by

Charles Weitfle

From the beginning of the railroad, difficulties with snow was a major problem. Pictured to the lower

right is a photo of a locomotive stuck in the snow. The photo, itself, is mislabeled and was

taken in March of 1869. Passengers included some dignitaries on their way to

Washington for President Grant's inaugural. the solution, adopted from almost the beginning was the

construction of snow sheds.

In January 1872, Susan B. Anthony travelled across the continent by train. After a stop in

Laramie, on January 1, she boarded the train to Cheyenne. With the snow on Sherman Hill, the train took five days including over a day

stopped in a snow tunnel. Miss Anthony wrote:

January 2. —Still stationary. The railroad company has supplied the passengers

with dried fish and crackers. Mrs. Sargent and I have made tea and

carried it throughout the train to the nursing mothers. It is the best we can

do. Five days out from Ogden! This is indeed a fearful ordeal, fastened

here in a snowbank, midway of the continent at the top of the Rocky mountains.

They are melting snow for the boilers and for drinking water. A train

loaded with coal is behind us, so there is no danger of our suffering from

cold.

* * * *

The train had

moved up to Dale Creek bridge and drawn into a long snow-shed. Here we

remained all night and, with the rarified air and the smoke from the engine,

were almost suffocated, while the wind blew so furiously we could not venture

to open the doors.

* * * *

January 4.—Morning found us still at Sherman and we did not move till 1 P. M.

There is another train ahead of us, and here we are, four passenger trains

pushing on for Cheyenne. The people from the different ones visit among

each other. Half-way to Granite Canyon the snowplow got off the track and

one wheel broke, so a dead standstill for hours. Reached Granite Canyon at

dark, a whole day getting there from Sherman, and remained over night.

January 5.—Bright and beautiful. Reached Cheyenne at 11:30 A. M

The Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz in his

Listy z podozy do Ameryki, "Letters and Portraits from America," Gazeta Polska, 1876, described

the snowshed on Sherman Hill:

We were approaching Cheyenne, a station in Wyoming, but before

reaching it we rode through the first snowshed, which was more than

a mile long. these snowsheds are extremely long galleries covered by a roof to protect the railroad

tracks from snowdirfts. I had heard so many tales and so much wonder about them that

I admit complete disappointment. It is true that these

galleries are very long, but also that they are nailed together of planks and

beams in the crudest manner. The beams are held together by nails -- in the roof

a multitude of holes -- in a word, the whole thing was built the way we used

to build houses a few decades ago. Although construction of this type can be

absolutely adequate, in no case does it warrant being regarded as the

eighth wonder of the world.

Sienkiewicz is today remembered as the author of Quo Vadis.

Train Stuck in Snow on Laramie Plains, 1869, photo by

C. R. Savage

As noted above, the caption on the photo is in error. The photo was actually taken in 1869, and was

apparently used as a later stock photo for a news story in 1887. Charles Weitfle (1836-1921), came to the

United States at age 13. He served as a photographer for the Union Army. In 1878,

he established a studio in Central City, Colo. and later had a studio in Denver. In 1883, his Denver Studio

burned, destroying approximately 1,000 plates. He then established a tent

studio in Cheyenne and also maintain a studio in Rawlins. About 1887-1889, Weitfle moved to

Granite County, Mont. and later to Phillipsburg. His son, Paul Weitfle, was also a

photographer in Colorado and New Mexico, but the two were estranged. [The writer gratefully acknowledes the

assistance of Paul Weitfle III for information concerning his great-grandfather.]

Snow has remained a problem. The winter of 1916-1917 was especially bad. In

late January, 1917, traffic on the road between Hanna and Laramie was interdicted by snow drifts

which the rotaries were unable to clear. The January 29 issue of the Laramie Boomerang reported that

the previous night fourteen dead engines were brought into the yard from

Rock River, most out of coal and all out of water. The paper continued:

It was reported at noon today that the plows, assisted by laborers, had

cleared one track long enough to get one train through to Hanna. However, the

tracks were drifted again shortly afterwards and two snow plows were

working to get another train through. Eastbound trains, however, are almost

hopelessly marooned. there has not been a regular passenger train from the west

since early Saturday morning and there is no telling when one will

get through. The drifting lets up at times for about an hour, but just about the

time a train is to be piloted through the wind comes up again and does

away with all the previous work.

Train Stuck in Snow, Rock River, January 1917

[Writer's note: The Daily Boomerang is probably the only newspaper named after a

mule. In first publisher, Edgar Wilson "Bill" Nye (1850-1896), founded the

paper in 1881, and named the paper after his mule "Boomerang." Two versions are given for

the naming of the mule: (a) the mule would follow Nye into a bar and would be shooed out. However,

the mule would return "like a boomerang;" and (b) the mule would leave its stable and

disappear for a few days, but would return "like a boomerang."]

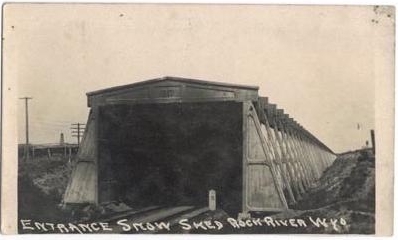

Snowshed at Rock River

Snowshed at Rock River

Note date over portal to snowshed, 1917. As a result of the difficulties in

1917, the Railroad established a plant at Rock River for making precast panels for

snowsheds. Prior to that time, snowsheds were constructed on an as needed basis, thus,

perhaps explaining the crude construction observed by Henryk Sienkiewicz. The plant

at Rock River is now gone.

Of course, it is possible that writers were impressed with the early snowsheds, because they were less than

impressed with the scenery. Robert Louis Stevenson in his Across the Plains, Chattus & Windus, London, 1892), describes

the scenery near Sherman Hill:

To cross such a plain is to grow homesick for the mountains. I longed for the

Black Hills of Wyoming, which I knew we were soon to enter, like an ice-bound

whaler for the spring. Alas! and it was a worse country than the other. All

Sunday and Monday we travelled through these sad mountains, or over the

main ridge of the Rockies, which is a fair match to them for misery of

aspect. Hour after hour it was the same unhomely and unkindly world about

our onward path; tumbled boulders, cliffs that drearily imitate the shape

of monuments and fortifications - how drearily, how tamely, none can tell

who has not seen them; not a tree, not a patch of sward, not one shapely

or commanding mountain form; sage-brush, eternal sage- brush; over all,

the same weariful and gloomy colouring, grays warming into brown, grays

darkening towards black; and for sole sign of life, here and there a few

fleeing antelopes; here and there, but at incredible intervals, a creek

running in a canon. The plains have a grandeur of their own; but here there

is nothing but a contorted smallness. Except for the air, which was light

and stimulating, there was not one good circumstance in that God- forsaken

land.

Two other aspects of the Pacific Railroad attracted the attention of the early writers,

Palace Cars, Hotel Cars, and dining facilities.

Interior Palace Car, 1877

A Palace Car was a premium service

offered by the Railroad. The cars featured plush carpeting, individual gas lamps for

the passengers, and at night, as illustrated in the next engraving, individual fold down berths.

Socializing, as illustrated in the above engraving, was conducted in the Parlor Car.

Palace Car, 1877. Left by night, right by day

Even more luxurious was the Hotel Car. In 1877, Mrs. Frank Leslie wrote in her husband's

newspaper:

You may have seen some of the sketches printed in our paper of the Pullman

Hotel Car in which we traveled. They really have the luxurious feeling of

home. Seats of plush velvet furnish the spacious living room. One party

can rent a hotel car to traverse the entire grade for a mere $120! A

well-equipped kitchen allowed us our meals cooked and served on board.

An ingenious system for running water has been installed; 20-gallon tanks

hang suspended from the ceiling of the kitchen.

Not mentioned in the newspaper was that the excursion in actuality cost a wee bit more than

$120.00. Although the hotel car was furnished by the railroad for free in exchange for

the publicity in the paper, the trip cost some $15,000.00. The hotel car, itself,

came equipped with a chef "of ebon color, and proportions suggesting a liberal sampling of the good

things he prepares." The meals were described by Mrs. Leslie in her 1877 book,

California: a pleasure trip from Gotham to the Golden Gate, as being "Delmonican

in * * * nature and style, consisting of soup, fish, entrees, roast meat and

vegetables, followed by the conventional dessert and the essential spoonful of

black coffee." The only sour note was, perhaps, the howling of the prairie

wolves, as the car passed through the countryside at the incredible speed of

20 miles per hour.

Meals, however, were not available on board for mere mortals traveling in the

Palace Cars or ordinary coaches. Meals were available in dining rooms established by

the Union Pacific in its hotels along the track. These facilities received mixed

reviews. Henry Williams wrote:

"Meals -- The trains of the Union Pacific Railroad are arranged so as to

stop at excellent stations, at convenient hours, for meals. The only

disarrangement is at Laramie, which seems to be unfortunate to passengers from

either direction. To travelers from the East it furnishes a very early supper, just after dinner at

Cheyenne, and to those from the West, it gives a very late breakfast, just before

dinner; but there is no other place for an eating-station, except at this point. At

Medicine Bow near Laramie, there is a little booth where the Western train coming

east about 7 A. M., often stops ten minutes for hot coffee, sandwiches -- an excellent convenience.

Usually all the eating-houses on both the Pacific Railroads are very excellent indeed. The keepers

have to maintain their cullinary excellence under great disadvantages, especially west of

Sidney, as all food but meats must be brough from a great distance.

Travelers need to make no preparations for eating on the cars, as meals at all dining-halls are

excellent, and food of great variety is nicely served; buffalo meat, antelope steak, tongue of all

kinds, and always the best of beefsteak. Laramie possesses the reputation of the best

steak on the Pacific Railroad. Sidney makes a specialty, occasionally, of

antelope steak. At Evanson you will see the lively antics of the Chinese

waiters, probably your first sight of them. Also they usually have nice mountain

fish. At Green River you will always get nice biscuit; at Grand Island they give all

you can possibly eat; it has a good name for its bountiful supplies."

Some diners complained that the antelope steak at Sidney was just another term for a very tough

beef steak. The facilities themselves were not operated by the Railroad, but by

concessionaires under lease. The principal operator was the Kitchen Brothers of Omaha. Charles W. Kitchen had primary

responsibility for the operation of the brothers' hotels in Wyoming, including the

Thornburg House in Laramie City, the Maxwell House in Rawlins, the Desert House in Green River City, and

the Mountain Trout House in Evanston. James B. Kitchen was responsible for the operation of the

Pacific House in St. Joseph, Mo. and Richard ran the company's properties in Omaha. The pride of the

company was the elegant Paxton House in Omaha which replaced Omaha's imposing Grand Central hotel which the brothers took

over after a foreclosure. The Paxton House was sold by Kitchen Brother in 1930. On September 24, 1878, a week before the scheduled grand re-opening of the Grand

Central, a careless workman left a burning candle in the newly constructed elevator shaft. In the resulting

confligration, the edifice was completely destroyed with five firemen losing their lives.

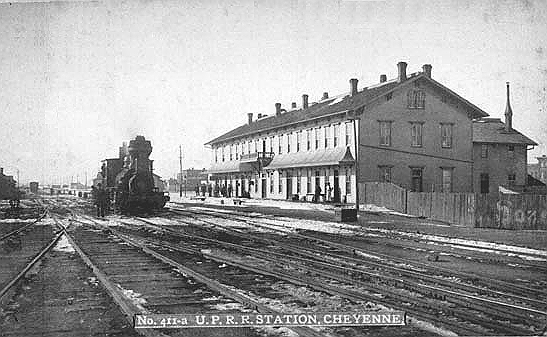

Union Pacific Depot and Hotel, Cheyenne, approx. 1880, photo by

Charles Weitfle, courtesy of Paul Weitfle, III.

It is doubtful that the rushed diners in the Cheyenne hotel had time to make note of the mounted heads of large game overlooking the

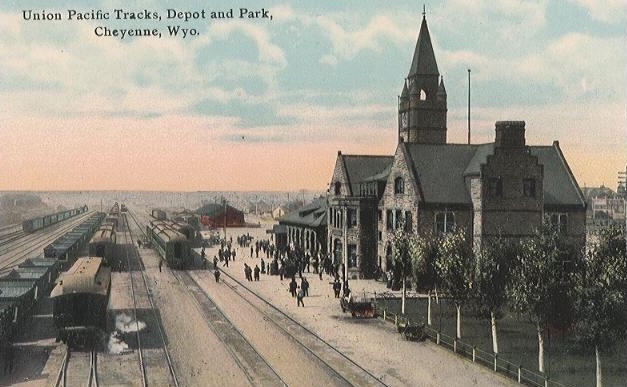

dining room from above.

The Cheyenne station was replaced in 1886 by the one pictured at the botton of the page designed by noted Boston and

Kansas City architects Van Brundt & Howe after a style promoted by Henry Hobbs

Richardson. The new terminal was one of four commissioned by Railroad President Charles Adams. The others

were the terminals in Omaha, Ogden, and Portland.

What, however, was not described by Williams was the scene at the railway station as the train paused to take on

water and coal; for the stop was only twenty minutes. The hordes of passengers scurried out of the

cars and into the station, placing their orders, and frequently having but five or fewer minutes in which

to devour the meal before the train departed. Indeed, there was the accusation that the food was

deliberately late since it was paid for when ordered. Thus, if the passenger did not have

time to eat his meal, it could be sold to passengers on the next train. Mrs. Leslie observed:

Generally, the stops to fuel and water the

locomotive are only 20 minutes long. What with having to clamber through

the ravenous crowd to first obtain one's meal, and then devouring the scant

victuals in one breath as they must, I'm sure every one of them suffers

terrible indigestion.

Owen Wister in his Lin McLean also described the waitresses and the effects of the haste with which the

meal was devoured in the twenty minute stop:

If you have made your trans-Missouri journeys only since the new era of

dining-cars, there is a quantity of things you have come too late for,

and will never know. Three times a day in the brave days of old you

sprang from your scarce-halted car at the summons of a gong. You

discerned by instinct the right direction, and, passing steadily through

doorways, had taken, before you knew it, one of some sixty chairs in a

room of tables and catsup bottles. Behind the chairs, standing attention,

a platoon of Amazons, thick-wristed, pink-and-blue, began immediately a

swift chant. It hymned the total bill-of-fare at a blow. In this

inexpressible ceremony the name of every dish went hurtling into the

next, telescoped to shapelessness. Moreover, if you stopped your Amazon

in the middle, it dislocated her, and she merely went back and took a

fresh start. The chant was always the same, but you never learned it. As

soon as it began, your mind snapped shut like the upper berth in a

Pullman. You must have uttered appropriate words--even a parrot will--for

next you were eating things--pie, ham, hot cakes--as fast as you could.

Twenty minutes of swallowing, and all aboard for Ogden, with your

pile-driven stomach dumb with amazement. The Strasburg goose is not

dieted with greater velocity, and "biscuit-shooter" is a grand word.

Writer's notes: "Strasburg goose," a goose which has been force fed to fatten its

liver; "bisquit shooter," a waitress.

The prices at the eating houses and hotels, like those in the captive eating facilities

in modern airports, also may have left something to be desired. An examination of the expense account for

a special federal agent, John T. Wallace, for August and September 1886,

reflects that dinner at Sidney cost $.75, his hotel bill in Cheyenne

(apparently including meals) was $5.65 (higher than his fees of $5.00 per day and much

higher than the average wage for a cowboy, which was slightly over $1.00 per day. It reminds the writer of a time

years ago when he was sent to Washington on business. The amount allowed on the writer's expense

account would allow him to either sleep in the hotel, or eat, but not both.), breakfast at Green River was $.75, and the hotel

in Evanston (apparently including breakfast and supper) was $3.75. In Denver,

Special Agent Wallace took the street car to the St. James Hotel. The fare was $.05, but the return to the

depot was by omnibus and cost $.25. The St. James' bill was $3.00.

Nor did Mrs. Leslie, as she supped on oyster soup, turkey, antelope steaks, quail, triffle with ice cream and cafe noir,

describe the conditions on the Union Pacific "emigrant cars." Robert Louis Stevenson took the emigrant cars and noted

that the Union Pacific cars

in which we had been cooped for more than ninety hours had begun to stink abominably.

Several yards away, as we returned, let us say from dinner, our nostrils were assailed by

rancid air. I have stood on a platform while the whole train was shunting; and as the

dwelling-cars drew near, there would come a whiff of pure menagerie, only a little sourer,

as from men instead of monkeys. I think we are human only in virtue of open windows. Without

fresh air, you only require a bad heart, and a remarkable command of the Queen's English,

to become such another as Dean Swift; a kind of leering, human goat, leaping and wagging

your scut on mountains of offence. I do my best to keep my head the other way, and look

for the human rather than the bestial in this Yahoo-like business of the emigrant train.

But one thing I must say, the car of the Chinese was notably the least offensive.

Dean Swift (1667-1745) was an Englist satirist.

Inerior, Emigrant Car.

Emigrant Cars were hooked to slow moving local freights which would have to give way for faster moving

express passenger and stock trains. Thus, the time to cross the continent was somewhat uncertain. The seats were

made of wooden slats. Over every two seats were overhanging shelves. The shelves would be supported by chains from

the ceiling. Getting on the overhead wooden shelves required a degree of contorsion. Sleeping as the coach swayed over the uneven tracks

added to the adventure of the westerward journey.

Stevenson's educated nose was not the only one to notice the aroma of the Union Pacific emigrant cars. Charles Merritt in

1885 observed:

During the years of '82-83, the writer was in the employ of the U. P. R. R., and his run

was between Cheyenne and Laramie, in Wyoming Territory. The cars containing the emigrants

were sent over the division attached to one of the regular freight trains, and the boys of our

crew always felt bad when it was our turn to convey the "pilgrims" over our run.

The herculean aroma that emanates from an emigrant car is peculiar to itself, and can be

found nowhere else. To say that it is something like a mixture of Limburger cheese, garlic,

and a bovine in an advanced state of decomposition, is but a faint comparison, but will give

the reader a vague and shadowy idea of what it resembles.

When the wind was favorable we could smell the coming emigrant train while it was yet afar

off, and it is a noticeable fact that the vegetation on either side of the track is dead, while

cattle, sheep and even skunks, have been discovered defunct near the line of the road with no

traces of violence upon their bodies. Their demise can only be attributed to the deadly

emigrant car odor. Even after a car had stood in the yard a week, and received a thorough

scrubbing and ventillating, the fragrance was as robust as ever.

The writer remembers seeing a tough looking tramp crawl out of a box-car, just ahead of

the emigrant cars, one cold night in December, when we had to stop to pack a hot box, and

after showing strong symptoms of sea-sickness, he inquired how far it was to the nearest

station. Being informed that it was only five miles he said : "Well, I'm glad of that, but

if it was 500 miles, I would rather walk and get fresh air than to ride any further where I

was."

Individuals from every nation are to be found traveling "emigrant." Swarthy Spaniards,

chattering Chinese, burly Germans, dusky Mexicans, Indians, and in fact, representatives from

all parts of the globe. Even the dude can be met with occasionally, and he never fails to ask

the train men the cause of "that beastly odah don't ye know." Of course a great many well

educated, cleanly and respectable persons travel in this manner, but they are in the minority,

and usually arrive at the end of their journey with their nasal appendages elevated about

five degrees above their proper position.

As quoted in IX, Fireman's Magazine, 1885, p. 460.

Union Pacific Depot, Cheyenne, 1910

More railroad photos are on the Laramie, Encampment, Rawlins, and Green River Pages.

|