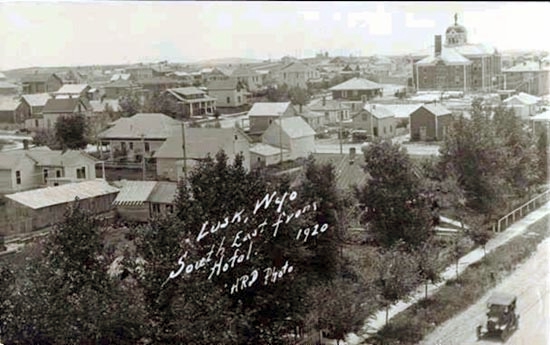

Looking Southeast from Hotel, 1920. Photo by

H. R. Daniels.

H. R. Daniels was a jeweler from Douglas.

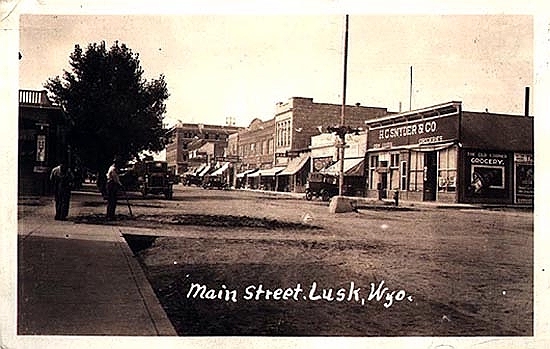

H. C. Snyder's store, Main Street, 1924.

Harry C. Snyder and his wife, Mary V. Snyder, arrived in the area before the

turn of the century. Snyder, in addition to his support for

the formation of Niobrara County, was a member of the Good Roads Club. He, additionally, among other things, donated the land upon which

St. Leo's Catholic Church was constructed. Mrs. Snyder served as

Grand Worthy Matron in the Order of the Eastern Star.

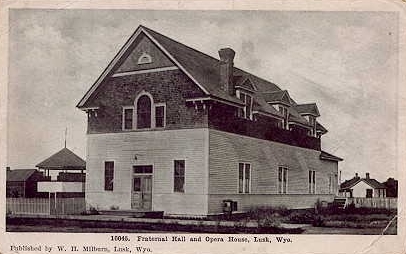

Lusk fraternal hall and opera house. The building later burned.

Lusk was founded in 1886, the year before

the discontinuance of the Cheyenne-Deadwood Stage Line discussed on a

previous page. A settlement had originally been located

a few miles west near the Silver Cliff Mine. When the railroad came in 1886, Frank S. Lusk (1857-1930),

a local rancher, owned the land upon which the town was to be located.

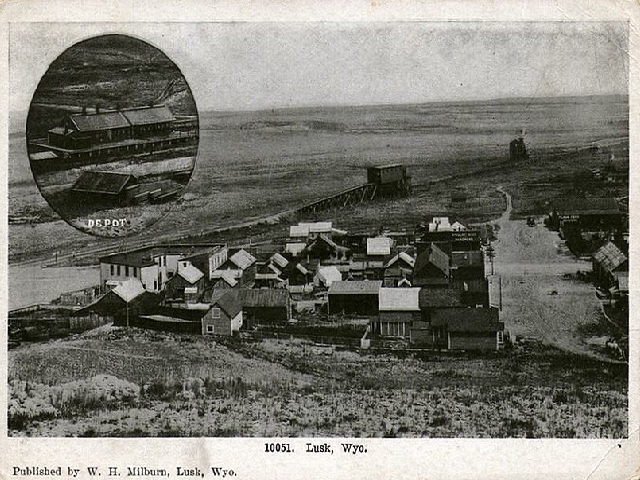

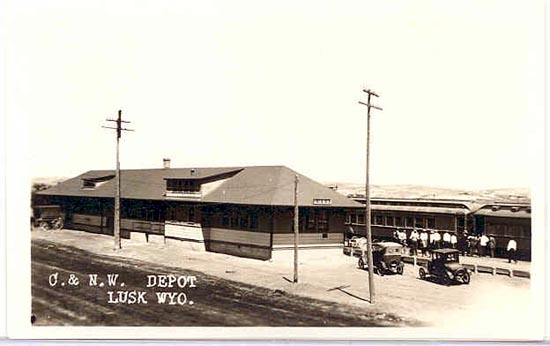

Lusk, circa 1918, looking east

On left is the Northwestern Hotel. The broad street running away from

the viewer is present day East 2nd Street. The depot was rebuilt in 1919. The Water tank was moved at that time from its original location.

Lusk Depot, approx. 1920

Henry Lusk came west at age 19 and entered the

cattle business in Colorado, but in 1880 moved his operations, the Western Live Stock Company, to

Node fifteen miles east of present-day Lusk. He later acquired land near the stage station at

Running Water. About 1884, Luke Voorhees, manager of the Cheyenne & Black Hill Express Company, applied for

a post office and named it after Lusk. Henry Lusk, however, acted as the first

postmaster. Henry Lusk became a railroad contractor and by 1910 had sold his real estate interests

in the area off to Tom Bell, L. J. Lohlein, and Harry Snyder and had moved to

Missoula, Montana, where he owned a bank.

For technical legal reasons when the railroad came, the right-of-way was required to be

owned by a corporation incorporated within the Territory. Since the only post office along the route of

the railroad was at Lusk, the town was born as the legal headquarters for the

Wyoming Central Railway which leased the line to the Fremont, Elkhorn & Missouri Valley Railway.

The Wyoming Central and The Fremont, Elkhorn & Missouri Valley were

consolidated in 1891. The railroad was purchased by the Chicago & Northwestern in 1903.

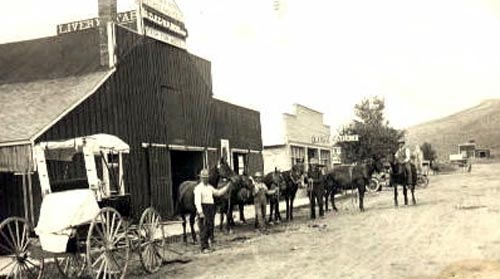

Livery, undated.

Note motorcar behind horses.

As with many "end of the line" towns, Lusk was

during its formative years a tad rough, Professor Larson referring to it as a

"miniature" hell on wheels, "without vigilantes." (Larson, 2nd ed, revised, p. 160.) An early example is the

tale of an individual known as the "stranger," and referred to by Justice Cole of the

Territorial Supreme Court simply as the "deceased." On October 9, 1886, the Stranger arrived in

town and booked his horse into Reddington's livery and then proceeded to imbibe at several of

the town's watering holes. At Johnny Owens' establishment, the Stranger apparently attempted to

impress one of the girls with the information that he was a horse thief and part of a gang camped about

four miles out of town. The girl imparted this information to Town Marshal Charles Trumbull who took the

Stranger into custody and convened a posse to capture the gang suspected of rustling horses in Johnson County.

When the gang could not be found, Trumble commenced to whip the Stranger and

threated to hang him from the water tank unless he would reveal the location of the

gang. At this point, the Stranger sobered up, revealed that the story of the gang was a josh, that his horse

was in the livery with a correct brand. When the Stranger's story checked

out, Johnny Owens urged Trumble to release the Stranger, couldn't Trumble tell that the

Stranger was only drunk? There then followed, apparently as a form of apology for the Stranger's

mistreatment, a tour of the town's drinking establishments with the tour ending at

Whittaker's Saloon. By then,

Trumble was quite drunk and asked the Stranger if he was friend or an enemy. After the

Stranger gave a somewhat noncommittal answer, in the words of Justice Cole:

Trumble drew a revolver, and pointed it at the deceased, working the hammer

back and forth, and again repeated his question and the deceased said: "I will have

to be a friend to you now." Trumble then told the deceased he was a coward, again raised

his pistol, and asked if he was a friend. The deceased said: "Do you want the truth? Well,

Charley, I don't like you."

Whereupon, Charley Trumble shot the Stranger dead. Charley was convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to

hang. Trumble

appealed on the basis that the judge gave an erroneous instruction as to malice. He also argued that the

conviction was fatally flawed in that Trumble was indicted by the Grand Jury for murdering one

Charley Miley. No one really knew who the Stranger was. Thus, the allegata

was inconsistent with the probata and, in legal contemplation, Trumble was not guilty. We all know that a legal contemplation is a

serious thing [Apologies to Sir Wm. Gilbert, The Gondoliers, 1889, "A legal fiction is a serious thing."] The

argument simply was Trumble was charged with killing Charley Miley. Even though the prosecution

proved that there was a dead body on the floor of Whittaker's and that Trumble did it,

, the prosecution did not

prove that the body was that of Charley Miley as charged.

Various witnesses admitted that they really did not know who the Stranger was, he being referred to at the

trial as Charley Miley, the "Prisoner," Gilliand, "Red Bill," "Gunny Sack Bill," and

Pete Gilmore. The Supreme Court did not buy the argument. The Court could not ignore the fact that all agreed that

Trumbull did the dirty deed.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court did agree that the judge's instruction to the

jury as to malice was defective and remanded for a new trial. Trumble pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was

sentenced to six years at Laramie with three years credit for time served.

Lusk, undated

Johnny Owens, in whose establishment the fatal adventures of the Stranger commenced, was one of Wyoming’s more interesting characters.

He came up the Trail from Texas prior to 1870. Owens operated a ranch at Chug Springs outside of Bordeaux.

In the 1880’s, he took over operation of the Hog Ranch at Fort Laramie. By 1886, the good times at Fort Laramie beginning to wind down.

With the coming of the railroad, Lusk, became the hot town. Thus,

Johnny opened his establishment in Lusk. With the extension of the

railroad to Casper, Lusk cooled down. In 1890, Owens moved on to Newcastle.

There, Johnny opened a dancehall and saloon locally

referred to as the “House of Blazes.” Legend in Newcastle is that the name referred to the number of gunfights which broke out within the saloon.

Whether the same is true or not is in reality unknown. The term “House of Blazes” was commonly used in the mid-Nineteenth Century to refer to a

saloon or other establishment with a reputation as a “hellhole.” In San Francisco one such facility was

operated by a Madam Johanna Schriffin. On one occasion a policeman had the temerity to follow

a thief into Madam Johanna’s establishment. Before the officer of the law could escape, the inmates and customers

had relieved him of his handcuffs, pistol, cap, and blackjack.

In the Hell’s Kitchen area of New York, another House of Blazes allegedly received its name because drunken patrons

would be set on fire for the amusement of the damsels within.

In New York another House of Blazes at 5 Batavia Street was a flop house Extraordinaire. The proprietor would fit

in each room some 12 guests in a 13 x 13 space, half in three bunks and half on the floor.

But then, the proprietor only charged a nickel a night for a spot.

Not withstanding Johnny Owens' ownership of the House of Blazes, or maybe because of it, Owens was elected as

sheriff of Weston County in 1892.

Main Street, 1920's.

During its "Hell on Wheels" days, the shooting of the Stranger was not the only shooting in Lusk. Four months later, Deputy Sheriff Charles

S. Gunn was shot to death in Jim Waters' Saloon by Bill McCoy. At the time Lusk was in Laramie County and, therefore, McCoy was taken to

Cheyenne for trial. He was found guilty of first degree murder and sentenced by Judge Samuel T. Corn to hang. He escaped from the

jail by filing through the bars with a hacksaw blade that had been concealed in the soles of another inmate's shoes. This, however,

was not the first time that McCoy had averted the hangman's noose by an escape. Unknown to Wyoming lawmen McCoy's real name was

Dan Bogan. Bogan when he had been drinking tended to become belligerent. Indeed, his belligerency when drinking is what got him in trouble with

Deputy Gunn. The two earlier had a confrontation in the Cleveland Brothers' Saloon.

In 1881 in Hamilton, Texas, Bogan had been drinking with a

friend, Davy Kemp. Bogan got into a confrontation with F.A. "Doll"Smith when Bogan refused to move his horse which

was blocking Smith's wagon parked near Cropper's store. Words led to a physical fight which led to some five shots being fired in the direction

of Smith. Smith did not attempt to fire his gun. The fifth shot hit its mark. Within minutes Smith was dead. Bogan and Kemp were charged

with murder in the first degree, a capital offense. Upon conviction Bogan and Kemp exited the courthouse by leaping out the

window. Kemp broke his leg in the leap and was recaptured. On an appeal, Kemp v. State, 11 Texas Court of Appeals, 174 (1881), the court held that Kemp was only

helping Bogan and, therefore, he did not have the necessary degree of malice to warrant hanging. Later,

Kemp was pardoned and became a sheriff in New Mexico. Bogan made good his escape, changed his name to W. A. Gatlin and continued his adventures in the

area of Tascosa, Texas. Tascosa, at the time, was where the cattle trail leading to Caldwell, Kansas, crossed the Canadian. Thus, it was amply supplied

with saloons. In 1886, Tascosa was the scene of the "Big Fight," a glorious five-minute shoot-out which started when Ed King, an L S cowboy, and

Lem Woodruff, a part-time bartender and former L S. Cowboy, vied for the affection of Sally Emory, apparently a lady of loose virtue. Four, including Ed King, were killed. Lem Woodruff and a cowboy,

John B. Gough, "the Catfish Kid" were severely wounded. The Catfish Kid received his sobriquet as a result of the perceived

resemblance of his eys to those of a fish.

After Bogan's escape from the Cheyenne jail, a posse was organized by Laramie County sheriff Seth Sharpless; Albany County Deputy Sheriff

Malcolm Campbell; former Albany County sheriff and Wyoming Stock Growers Association Chief of

Detectives Nathaniel K. Boswell; and stock detective Frank Canton. The posse suspected that Bogan may have taken refuge on the Keeline

ranch outside of Lusk. Unbeknownst to his fellow members of the possee, Canton, himself, was wanted under a different name in

Texas. See Johnson County War. There may have been good reason for their suspicions of Keeline involvement. Reputedly many, if not all, of the

range riders for the Keeline had notches on their guns and were wanted in Texas. The posse was unsuccessful.

Prosecuter Walter Stoll, who later

prosecuted Tom Horn, called in the Pinkertons who assigned Charles Siringo to the case. Siringo, pretending to be a wanted outlaw himself,

gained the confidence of the Keeline riders but learned that Bogan had already taken off for Utah on the Keeline foreman's, favorite horse. From Utah,

Bogan returned to Tascosa stopping off on the way at Los Portales Lake to see Woodruff whom Bogan had known from when the two

participated in a cowboy strke. From there, Bogan travelled to

to New Orleans and then sailed to Argentina. Unknown at the time, but learned later, was that the Keeline foreman, Tom Hall, was

himself, wanted in Texas for murder under his real name of John "Tom" Nichols. Years later it was learned that Hall arranged for the hacksaw blade to be

sneaked into the Cheyenne jail and that he had arranged for the gettaway horse outside the jail. Hall ultimately moved to

Price, Utah, where he ran a saloon under his real name. Nichols, had a brother William M. "Mid" Nichols who at one time

ran a saloon in Baggs, Wyoming. In Baggs, Mid Nichols helped conceal Butch Cassidy. Later Mid moved to Pioche, Nevada, where he also

operated a saloon. Siringo suspected that Bogan changed his name once again and returned to the

United States.

Next page: Lusk Continued.

|