The text of the ad was composed by Ned Jordan (1882-1958), president of Jordan Motor Car Company.

on a train crossing the Laramie Plains. He was inspired by the sight of a girl on a horse racing the train. Between Laramie and Bosler the Lincoln

Highway, now US 30, parallels the Union Pacific and was the apparent scene depicted. Fred Cole (1893-1967),

the artist, also did illustrations for other auto manufacturers. "Somewhere West of Laramie" is regarded as having

changed the whole nature of automobile advertising. Until then crossing the continent by

motorcar was an illustration of the reliability of the cars. Another ad for the Jordan Victoria composed by

Jordan and illustrated by Cole entitled "In the Middle of the Night" drew the ire of the New York Society for the Supression of Vice. To see the

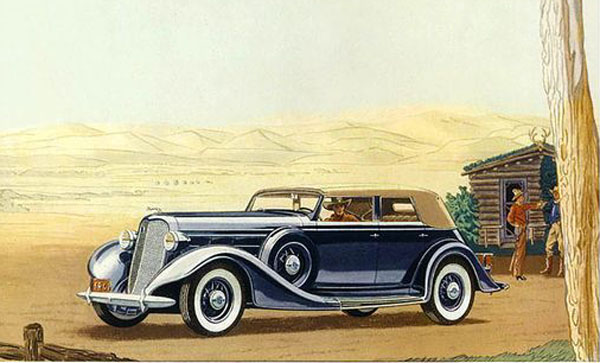

offending advertisement Click here. During the 1930's automobile advertisement often

seemingly evoked in the reader subconscience images they might want to project of being a robust man of the west. An examble might be a

1940 advertisment for a Lincoln LeBaron Convertible Sedan, a vhicle that in

2018 dollars cost an amount equal to approximately $133,300.

1940 Illustration for a Lincoln LeBaron Convertble Sedan .

The text of the advertisement advised, "An owner's demands upon Lincolns are varied and

unique. In his motor car, a cowboy travels daily to a sheepcamp miles across the

sage brush."

1940 Illustration for a Lincoln-Zephyr.

"The Lincoln-Zephyr Approaches A Ranch In Wyoming."

As previously indicated prior to World War I, the roads in the Amrican West were abysmal.

In 1907, a Paris newspaper, Le Matin,

sponsored an automobile race from Pekin to Paris. As a result of the race's success, an

around the world race was sponsored the next year by the Le Matin and the

New York Times. As originally envisioned, the entrants would proceed from New York to the west coast of the United States,

north to Alaska, across the ice to Siberia, and onwards to Paris. In the actual race, the

cars were shipped by steamer to Russia via Japan and the Alaska leg was skipped. On Lincoln's

Birthday, 1908, an estimated 250,000 gathered in Times Square to see the

six entrants off, each car had a driver and several on-board mechanics. Entering the race were a Thomas Flyer (U.S), a Zust (It.),

a Protos (Ger.), a De Dion (Fr.), a Motobloc (Fr.), and a Sizaire-Naudin (Fr.). The

Sizaire-Naudin broke down before reaching Albany, N.Y. Near Chicago, the Thomas was bogged down in

snowdrifts, some as high as 30 feet. In one instance it took ten horses to pull out the Thomas. The Motobloc broke down in

Omaha and was shipped to Seattle by train resulting in its disqualification. In Grand Island, Neb., the

De Dion was delayed by two days because of a broken shaft. It made up for lost time

by making the 6 miles from Gibbon to Shelton in only 9 minutes. In the countryside the

going was slow because of the frequent gumbo quality of the roads. In towns schools would be let out so students

could witness the vehicles and their pilot cars fly by at the astounding speed of 25 mph.

When Cheyenne received word received that the

Thomas was first in crossing Nebraska, the Industrial Club made plans for its arrival.

When the vehicle reached Pine Bluffs, Cheyenne would be notified by telegraph. Twenty automobilist with their machines

decorated with flags from the

Capitol Garage would head east

to meet the Thomas at Archer. When the Thomas and the accompanying entourage reached a point four miles east of

Cheyenne, the City would again be notified by telegraph and all of the steam whistles in the city

would be sounded. That night March 8, there was a banquet at the Industrial Club.

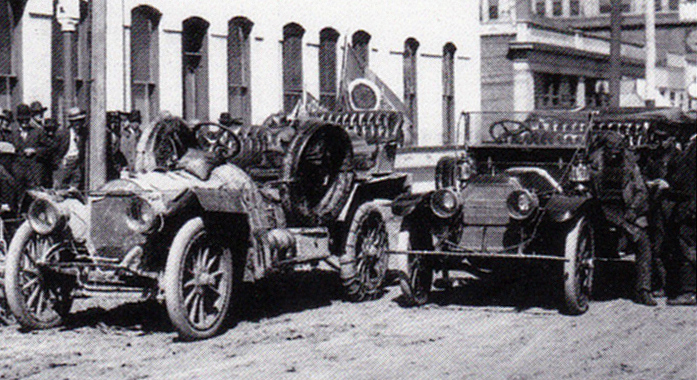

Thomas with pilot car in fromt of Capitol Ave entrance to the

Interocean Hotel, March 1908.

As indicated by the chains on the tires of the vehicle, roads were not very good. See closeup next photo. In the background of the photo is the

Cheyenne Opera House.

Closeup of the Thomas showing chains the rear wheels. The chains were not for snow but for the mud.

Note the number of spare tires on the vehicle.

On March 12th the Zust arrived in Cheyenne. Again, the Industrial Club hosted a banquet for the crew of the

Italian Car. The car laid over for a day for repairs. In the meantime the

Thomas had reached Granger where it met snow.

Zust, location unidentified.

Four miles west of Granger, the Zust ran into problems. It was delayed was delayed by twenty hours freeing the vehicle

from mud in a washout. Block and tackle borrowed from the railroad had to be used. Further on

near Spring Valley about 14 miles southeast of Evanston they ran out of gasoline. Even though Spring Valley was an oil

field, there was no gasoline to be had. Fuel was required to be shipped in from

Evanston.

Spring Valley, Wyoming, 1907.

Additionally, the Zust, lost traction in the snow.

A pack of about fifty wolves circled the car. In the snow

the machine was unable outrun the pack. The car's horn and, which failed to

spotlight was unable to frighten the animals away.

The crew of the car fired rifles and killed a few of the worlves. Some of the

surviving wolves started eating some of the dead.

Other wolves kept up the attach on the car. Finally just before ammunition ran out,

remaining wolves ran away.

Illustration by Edward Patrick Kinsella, (London) Penny Illustrated Paper and

Illustrated Times, March 28, 1908. Wolves attacking Zust, near Spring Valley Wyoming.

The Penny Illustrated Paper was published between 1861-1913). Kinsella (1874-1936) was a well-known artist and illustrator famous

for among other things his illustrations of cricket.

.

Good sometimes comes out of bad. Local

trappers the next day gathered some twenty pelts and collected $200 in bounty. See

Motor Age, March 26, 1908, p. 18 and New York Times, "Italian on Zust Kill 20 Wolves,"

March 21, 1908. For discussion of wolfers and bounties, see Wolfers.

Entrant into Great Race, west of Cheyenne, with Studebaker pilot car foreground, March 1908.

The above scene appears to be somewhere between Buford Station and Tie Siding. The road is not atypical. Montague

Roberts, the Thomas driver, described some roads as being tracks of

"fresh cooked molasses candy." The vehicles of the "Great Race" were not, however, the first

to traverse the continent. In 1903, George Wyman drove from San Francisco to New York on

a motorbike. Near Telephone Canyon, he got stuck in the gumbo and had to

secure a team of horses to pull the 90 pound bike out of the mire. Indeed,

the mire was so thick that the bike was stuck bolt upright and did not fall over. Wyman described

the mud:

Down at the bottom I struck gumbo mud, and it stuck me. Gumbo is the mud

they use in plastering the crevices of log houses. It has the consistency

of stale mucilage and when dry is as hard as flint. It sticks better than

most friends and puts mucilage to shame. When you step in it on a grassy

spot and lift your foot the grass comes up by the roots. My wheel stood

alone in the gumbo whenever I wanted to rest, and that was pretty often.

Every time I shoved the bicycle ahead a length I had to clean the mud off

the wheels before they would turn over again. I kept this up until finally

I reached a place where I could not move the bicycle another foot.

It sunk into the gluey muck so that I could not shove it either forward or

backward.

In 1909, Alice Huyler Ramsey, the 22-year old president of the

Women's Motoring Club of New York, followed the same route in a Maxwell-Briscoe. In

Cheyenne she engaged the services of a pilot car to guide her to Laramie. The pilot car

got stuck and had to be pulled out with the Maxwell.

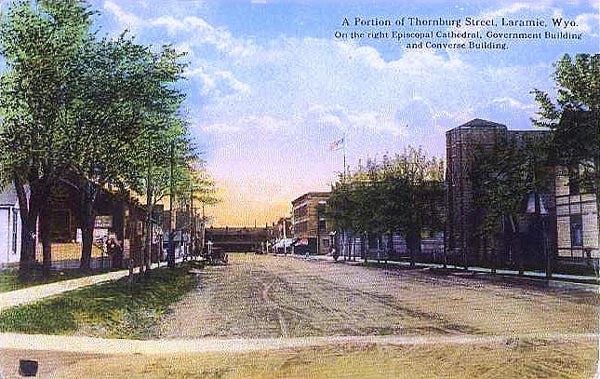

Automobilists, Thornburg Ave., Laramie, 1911, looking west.

Automobilists, Thornburg Ave., Laramie, 1911, looking west.

The cars in the Great Race would generally

follow roads paralleling the railroad. Onward through Wyoming the cars progressed along a route that

later became the Lincoln Highway and later U.S. 30 to Salt Lake City. In Salt Lake City, the Protos broke down and

was shipped by train to Seattle for the repairs. The remaining vehicles proceeded on to

San Francisco and then shipped to Seattle. From Seattle the cars were shipped by Steamer to

Kyoto and from there to Vladivostok, where the cars resumed their trek across Siberia following the

Trans-Siberia Railroad to St. Petersburg. The first to reach Boulevard Poissoniere [Fishwife Boulevard] in Paris was the Protos on July 26, followed by

the Thomas on July 30, and the Zust on Sept. 17. The Thomas was, however, declared to be the winner with the Protos being penalized by

30 days for taking the train to Seattle.

The following year, 1909, M. Robert Guggenheim, heir to the Guggenheim fortune, sponsored another race from

New York to Seattle, ostensibly to assist the "good roads" movement. Entrants were two factory sponsored Fords, a factory Acme,

a factory Shawmut, a Stearns owned by Oscar Stolp who drove notwithstanding the opposition of the

Stearns Motor Company, and an Italia owned by Guggenheim. Guggenheim did not drive himself, but

instead hired a professional crew. Guggenheim proceeded on to Seattle where, among other things, he received

a speeding ticket for driving a high-powered automobile. In the east, speed limits were strictly enforced and the

cars were limited to various speeds of less than 20 mph. As an example, between Syracuse and

Buffalo, N.Y., the speed limit was 15 mph. West of St. Louis, however, there were no speed limits.

Thornburg Ave., Laramie, 1910

On June 1, five of the entrants were off, following a lead escort of New York policemen on bicycles, all the way to the

city limits. The Stearns followed four days later, but perhaps proving the wisdom of

Stearns' opposition to the race, broke down only 24 miles out of the city.

The Fords weighed only one-fourth the weight of the other cars and had been stripped of all excess weight, including

windshields, back seats, and tops. Indeed, they consisted of little more

than a chassis and seats. While the other cars had a crew of three or four, the Fords relied on

local dealers for maintenance and as guides and, thus, bore only a driver and relief driver, saving even

more weight. Indeed, the Fords were so light that when they got stuck, the drivers merely picked the cars

up and put boards under the wheels, while the others would require horses to pull them out of

the mire. Local Ford dealers acted as guides for the Fords, while the Acme, the Shawmut, and

the Italia were repeatedly delayed by getting lost on the unmarked roads. Ford apparently left nothing to chance.

The drivers of the Acme and the Shawmut complained bitterly that Ford had, among other things, bribed

a ferry operator to delay the Shawmut and had illegally changed an engine

and made other repairs to the Fords. In Wyoming and Utah, the Shawmut and the Fords ran neck and neck.

On June 23, Ford No. 2 arrived in Seattle, followed 17 hours later by the Shawmut, and the next day by the

other Ford, and a week later by the Acme. Guggenheim's Italia dropped out in Cheyenne. Ford immediately started an

a publicity campaign advertising that its winnimg vehicle was a "standard stock car and exact duplicate" of Model T's

available at local dealers. Five months later, unpublicized, the Ford was disqualified because of rule violations and

the Shawmut declared the winner. Years later

a mechanic for Ford admitted that an overeager local Ford dealer may have changed the engine when the mechanic wasn't looking.

Music this page: "Somewhere in Old Wyoming' as recorded for Victor by Joe Green's Orchestra, 1930.

Next: Bosler and Rock River.