|

Administration Building, 1880's

The Administration Building was constructed in 1885 of a lime grout. As shown in

the next photo, the building is now in ruins. The building

in addition to housing the post adjutant's office, contained a library, school, and an

auditorium. Life on isolated posts in the West could be monotonous. Libraries and auditoriums provided

an opportunity for self-created entertainment. Elizabeth Custer in Boots & Saddle: Or Life in Dakota

With General Custer made note of such self-entertainment at Fort LIncoln:

The soldiers asked the general's permission to put up a place in which they could have

entertainments, and he gave them every assistance he could. They prepared the lumber in

the saw-mill that belonged to the post. The building was an ungainly looking structure,

but large enough to hold them all. The unseasoned cottonwood warped even while the house

was being built, but by patching and lining with old torn tents, they managed to keep out

the storm. The scenery was painted on condemned canvas stretched on a frame-work, and was

lifted on and off as the plays required. The footlights in front of the rude stage were

tallow-candles that smoked and sputtered inside the clumsily cobbled casing of tin.

The seats were narrow benches, without backs. The officers and ladies were always invited

to take the front row at every new performance, and after they entered, the house filled

up with soldiers. Some of the enlisted men played very well, and used great ingenuity in

getting up their costumes. The general accepted every invitation, and enjoyed it all

greatly. The clog-dancing and negro character songs between the acts were excellent.

Indeed, we sometimes had professionals, who, having been stranded in the States, had enlisted.

Anson Mills as a young captain describes in his 1918 biography

My Story being assigned in the 1870's to Fort D. A. Russell near Cheyenne. There he discovered that he had been

appointed as the "permanent chairman" of a committee. It was the first time that he had ever been

asked to asked to be the permanent chair of an Army panel. Unfortunately, it was the entertainment committee charged with putting on

monthly activities. Three young lieutenants were designated to plan and to assign roles for the first play,

Samuel Warren's tragic-comedy Ten Thousand a Year. The junior officers had their revenge. Captain

Mills found himself playing the lead of Tittlebat Titmouse, a draper's assistant who comes into

a fortune though the use of documents forged by his lawyers. Titmouse takes a seat in

Parliament, but is blackmailed by the lawyers. Thus, Mills discovered himself on stage in knee

breeches, cane, and wig made of angora wool. The significance of the wig is that Tidmouse's hair is

described as a "crop of busy, carrotty hair." In one scene from the novel upon which the play was based,

Tidmouse dreams of having black hair and, thus, goes to a chemist's shop for hair dye. Warren wrote,

"Titmouse bought the specific, hurried home, read with

delight the remarkable testimonials on the wrapper, and that night

rubbed the stuff into his hair, whisters, and

eyebrows with all the energy of hope." Warren continues:

"He could not sleep for several hours. He dreamed a rapturous dream, --that he bowed to

a gentleman with coal-black hair, whom he fancied he had

seen before, and suddenly discovered that he was only

looking at himself in a glass. This

woke him. Up he jumped, and in a

trice was standing before his little glass.

Horrid! He almost dropped down dead! His hair was perfectly green!--there was no

mistake about it. He stood staring in the

glass in speechless horror, his eyes and

mouth distended to the utmost, for several minutes. Then

he threw himelf on the bed, and felt

fainting. Up he presently jumped again,

rubbed his hair desperately and wildly about, again looking

into the glass; there it was, rougher than before;

but eyebrows, whiskers, and head, all were, if

anything, of a more vivid and brillant green."

[Writer's notes: It has been suggested that Warren's novel should be read by students of the law. See

"Samuel Warren: A Victorian Law and Literature Practitioner,"

C. R. B. Dunlop,

Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature, Vol. 12, No. 2

(Autumn - Winter, 2000) , pp. 265-291. The question may be asked whether in light of the

forgery or the blackmail of the client, whether the work is to be read in

conjunction with the classes on evidence or classes on ethics. Warren, himself, was a

lawyer. He served in Parliament and was appointed to a "mastership in lunacy." As noted by the 1911

edition of the Encylopedia Britannica, Warren was "a determined opponent of the rising school of

medical alienists who were more and more in favour of reducing certain forms of

crime to a state of aberration which should not be punished outside of asylums."]

Administration Building, 2001, photo by Geoff Dobson

Other buildings which are now in ruins include the officers'

quarters depicted in the next photographs

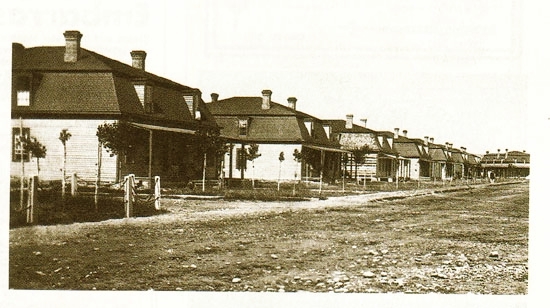

Officers' Quarters, 1880's

The above buildings were also constructed of lime grout. The three buildings consisted of

two duplexes plus the commanding officer's quarters. Only the commanding officer's quarters

had inside plumbing. Each was constructed in accordance with a standard Army design utilized

elsewhere in the west, the only difference being materials. Compare with

view of officers' quarters at Fort Keogh below. Each side of the duplexes contained 1,250 sq. ft with sitting

room, parlor, dining room, and kitchen. The second floor had two or three bedrooms.

Officers' Quarters, Fort Keogh, Mont., undated

The Officers' Quarters at Fort Keogh were built of wood, while the buildings at

Ft. Laramie were of lime grout, a locally produced cement.

Officers' Quarters, 2001, photo by Geoff Dobson

Beyond the Officers' Quarters is "Old Bedlam."

The concrete houses were constructed in 1881 as additions to older, smaller structures.

Infantry Barracks, undated

At the left is the Infantry Barracks, constructed in 1867, located at the

northeast side of the Parade Grounds. The frame building housed three companies. In the center

of the photo is the "New" Guardhouse built in 1876 in response to complaints by the

post surgeon as to conditions in the old guardhouse. At the right hand side of the

photo is another infantry barracks constructed in 1866. Only foundations are left of the

two barracks buildings.

Infantry Barracks, 2001, photo by Geoff Dobson

In the foreground on the opposite side of the road, are the

foundations of the Infantry Barracks depicted at the left in the upper photo. In the distance on

the right is the Cavalry Barracks constructed in 1874. In the center of the photo on the hill are the

ruins of the post hospital, close-up on preceding page. At the left is the Sutler's Store, also

depicted on the preceding page.

To the left of the Sutler's Store is the Lt. Colonel's Quarters, now referred

to as the "Burt House" constructed in 1884 and named after Lt. Col. Andrew Burt, stationed at

Ft. Laramie twice. Burt also served as commander of Ft. C. F. Smith constructed to

protect the Bozeman Trail and also participated in the Battle of the Rosebud. The Burt House is noted for having housed the largest colony of bats at the fort. At one

time as many as 3,000 bats made their home in the house. Unfortunately, bat urine is highly acidic and

caused extensive damage to the house. The Park Service has now "bat proofed" and restored the structure. the Cavalry Barracks constructed in 1874. In the center of the photo on the hill are the

ruins of the post hospital, close-up on preceding page. At the left is the Sutler's Store, also

depicted on the preceding page.

To the left of the Sutler's Store is the Lt. Colonel's Quarters, now referred

to as the "Burt House" constructed in 1884 and named after Lt. Col. Andrew Burt, stationed at

Ft. Laramie twice. Burt also served as commander of Ft. C. F. Smith constructed to

protect the Bozeman Trail and also participated in the Battle of the Rosebud. The Burt House is noted for having housed the largest colony of bats at the fort. At one

time as many as 3,000 bats made their home in the house. Unfortunately, bat urine is highly acidic and

caused extensive damage to the house. The Park Service has now "bat proofed" and restored the structure.

Upper Left, "Burt House," photo by Geoff Dobson.

|