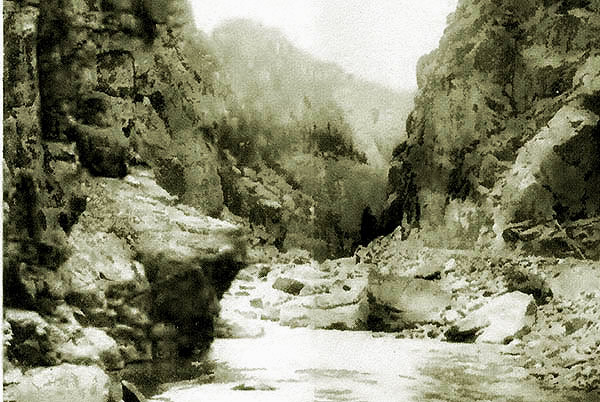

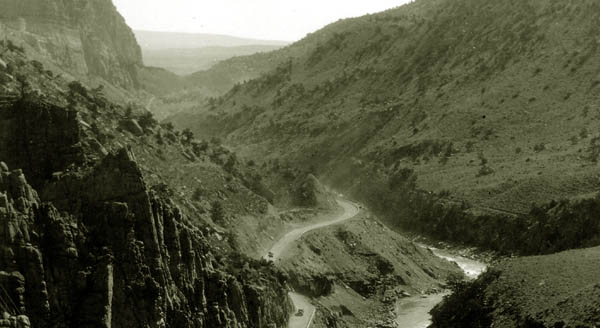

Cody Road in Shoshone Canyon,1909.

Even after completion of the New Cody Road following construction of the reservoir, the

road above the reservoir was not realy suitable for motor cars until 1916. Tourists visiting the park used pack trains

or spring wagons. The schedule published by the Burlington Railroad for visiting the Park from Cody entailed leaving Cody at 8:00 a.m., arriving at Wapiti at 4:00 p.m.

The next day one would arrive at Pahaska at 1:00 p.m. and finally the next day arrive at Sylvan Lake in the Park at noon.

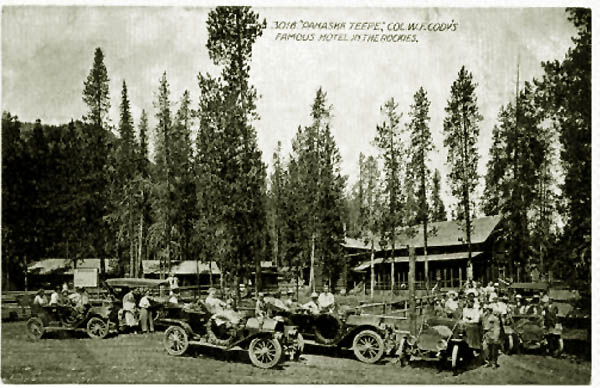

Pahaska Teepee, approx. 1920.

In anticipation of a road from Cody to Yellowstone, Colonel Cody selected

the location for Pahaska in 1901 selected the site for the Pahaska Teepee. It was 1 1/2 miles from the

entrance to Yellowstone Park at the confluence of the North Fork of the Shoshone and Middle Creek.

Pahaska was an Indian name for Cody (see Buffalo Bill).

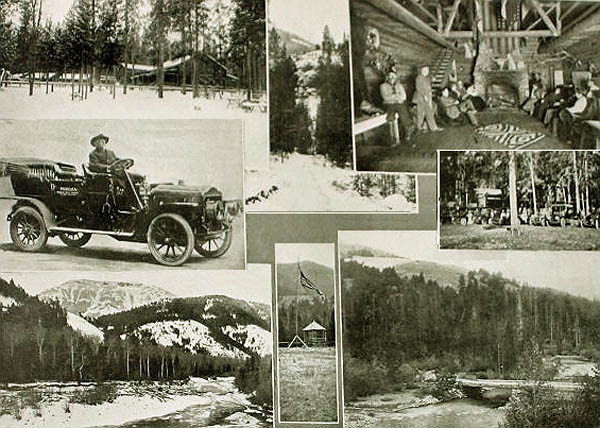

Photo Montage of Pahaska Teepee, approx. 1911, by A. G. Lucier.

Photo Montage of Pahaska Teepee, approx. 1911, by A. G. Lucier.

The automobile is a White steamer used to bring guests to the hotel from

Cody. The steam-powered automobile would leave daily from the Irma at

noon and would arrive at the Pahaska in time for dinner. The automobiles

were introduced in 1909 at the urging of Jake Schwoob, manager of the Cody

Trading Company who was an early automobile enthusiast. Indeed,

when registration plates were introduced in the state, Schwoob was

honored by having license plate number 1.

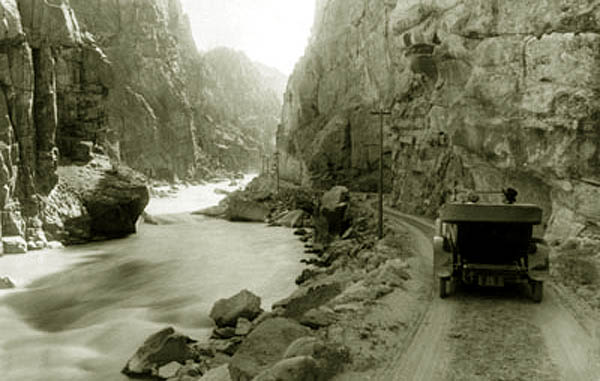

Cody Road in Shoshone Canyon, undated.

Although the Northrn Pacific and the Burlington showed

interest in utilzing the Cody Road as an additional route into the Park, there was no great incentive to improve the road

above the dam. Plans for improvement to the road were put on hold with the United State entry into World War I and the nationalization of the railroads by the

Wilson Administration. Not withstanding that the park was not open to automobiles until 1916, two automobiles ventured up to

Sylvan Pass in 1914.

Two automobiles at Sylvan Pass, July 1914.

During the fiscal year 1917-1918, the road was hardly open at all, first due to a flood washing away

the road, secondly snow, and finally in 1918, all money for maintenance was cut off.

In 1919, the Department ofthe Interior reported as to the Cody Road:

"The eastern entrance, or Cody Road, was also badly damaged both within the park and through the national forest east

of the park, which road is also maintained and improved by this department.

Not less than 12 serious washouts occurred, some of which were several

hundred feet in length, and all of which required rock or timber revetment

to prevent the Shoshone River from again washing out these pieces of road.

Considerable damage was also done to the new steel bridges recently erected, as the abutments were badly undermined and settled and the approaches were washed out.

In 1920, the Department reported that dangerous stretches on the Cody Road must be graveled.

It also recommended that the work of parapet construction should be vigorously continued until every point on the road system that is

dangerous on account of steep slopes below the highway is made safe.

Not withstanding the danger,

several cars ventured up the Cody Road as far as the Holm Lodge located near

Gunbarrel Creek about seven miles from the eastern entrance to the park. In 1912, Aron Holm purchased a Stanley Motor Wagon from the Stanley Motor Carrage Company.

He subseqently purchased three more vehicles from

Stanley which were used for transportation of tourists to and from the Lodge. From the lodge the tourists were transpoted to and through

the Park by horse-dawn vehicles and then returned to Cody in the cars. Additionally, Col. Cody acquired a White Steamer for transportation to his

Pahaska lodge to the east of the Holm Lodge. As indicated, the Government forced park concessionaires to consolidate and on April 29, 1915, the Holm

Transportation Company went into bankruptcy. It was, however, able to finish out the season.

Three of Holm's steam powered cars at Gunbarrel Creek.

Holm Transportation Company Stanley Steamers at Gunbarrel Creek.

Even after the end of the war, the road east of the Dam provided adventure to tourists coming up

from Cody in motor busses. The road in Shoshone Canyon was one-lane, with sharp curves perched on narrow ledges with minimal

"parapets" above

the Shoshone River. The tunnels also provided interest to the intrepid motorist. Indeed, the Cody Road at that time brings to mind El Camino de la Muerta connecting La Paz to

the Amazonian protion of Bolivia. The writer's youngest son, always adventuresome,took the Road of Death back to

civilization following some time in the Amazonian jungle. When the writer visited the Amazonian jungle, a fellow

member of the writer's party, himself from the South of India, warned against consuming anything

except bottled beer. "Dangerous, Dangerous" he commented. The road was like the food in the Amazon, "Dangerous, Dangerous."

Cody Road looking east, approx.

1926.

In 1920 Chicago physician Theodore Bacmeister drove the road in his Franklin car. The road was such that Dr. Bacmeister though

that it might turn one's hair

white. He wrote of his adventures in the Clinique, Vol. 42,p. 58, "Westward Ho, via Automobile":

Climbing from Cody into the Yellowstone National Park via Sylvan Pass

the autoist gets his first taste of real mountain driving. Also, he puts

his motor to its first real test as a hillclimber! Mountain-driving is

wholly a matter of education. One acquires a taste for it only after due

experience and successive thrills. Unfortunate indeed is that tourist whose

initiation into this perilous but exhilarating pasttime is the drive

in the Park "bus" over the road now under discussion. The drivers of these

huge yellow cars are thoroughly competent, safe and sane—otherwise they

had been dead long since—but they are young, lusty, and always in a hurry,

and the way they push up and down these hills is quite enough to turn a

"first-trip" passenger white-haired. It is nothing short of refined cruelty

to jounce a bunch of "tenderfeet" over this road and many a man is forever

cured of any thought or ambition which he may have for mountain touring

by these thoughtless youths on this really safe and wonderful drive.

One should acquire the taste for mountain travel by degrees—as one acquires

the taste for olives, a bite one day and then two bites the second day!

It is well to start in with the eastern hills and mountains and tackle the

"rough stuff" of the west only after a thorough tryout in the less

fearsome places. Our education began in Illinois and Wisconsin, was

continued in the Berkshires, the White and the Green mountains, and

finally polished off in the Rockies. I might add that the climax of all

mountain driving came to us in the far famed Kootenai Canyon in northern

Idaho. The twelve miles of this road, built along the edge of the cliff,

somewhere between the sky and the foaming river, will thrill the hardiest

auto-hobo and will send a tenderfoot to the hospital with nervous

prostration!

After dipping over the edge of the cliff at Cody and dropping sharply

down to cross the river, the road begins the long, steady climb through

Shoshone Canyon, past the great dam—- which is hung six thousand feet above

sea level—through the Shoshone National Forest Preserve, with its beautiful

timber,tossing mountain streams and weird rock formations (each with its

appropriate name marked for the traveler whose imagination lacks

somewhat), past Buffalo Bill's old hunting lodge, Pehaska Tepee

(now a most popular resort), to the boundary of the Park.

Here one makes his peace with the Rangers, pays his fee of $7.50, and

enters that greatest of all the world's playgrounds, Yellowstone National

Park.

Touring Car rounding curve on Cody Road, approx.

1926.

Tunnel on Cody Road east of the Dam Hill, approx.

1926.

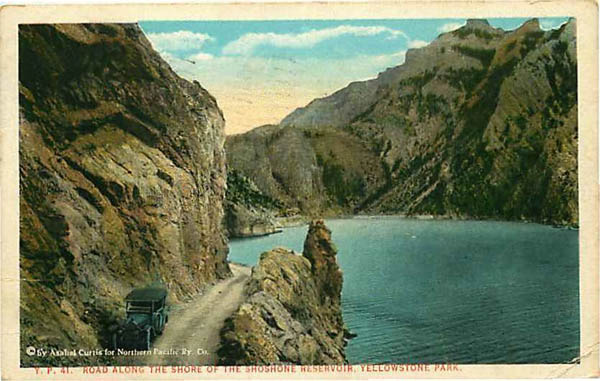

Motorcar parked in lay-by on the drive along northside of

Reservoir. Photo by Anahel Curtis, approx. 1924.

Anahel Curtis (1874-1941) was a well known Seattle photographer. He was not, however, as famous as his brother

Edward Curtis famous for his photographs of American Indians. Anahel Curtis was at one time

a parther of his brother but the two separated over an alleged dispute over credit for photographs. In 1922, he was appointed as

the "official" photographer for the Northern Pacific Railroad. About 1924 he did a series of photographs of Yellowstone for the

Railroad which were used in books, brouchures, postcards, and menu cards for the railroad. Most of the postcards and books were published

by Bloom Brothers of Minneapolis. Up until 1916, F. J. Haynes had been the offcial photographer for the

railroad. In 1916, however, the National Park made Haynes the exclusive photographer for the park. This resulted in a dispute

with the Park which was not resolved until 1930 when Bloom Brothers gave up publication of

Yellowstone photographs.

View of Resevoir

Next Page: Cody Road Continued.