Col. Cody and the Wild West show saluting Her Majesty, the Queen, 1887.

As observed on the preceeding page, initially Cody's Wild West show included in addition to Buck Taylor, Doc Carver and

Capt. A. H. Bogardus. Soon with regard to Doc. Carver, there was a falling out, with Doc Carver organizing his own

"Original Wild West." In April, 1884, both shows were appearing in St. Louis with the result that the two sides battled it out in Court Room No. 2.

Col. Cody's lawyers brought an action for an injunction to restrain Doc. Carver from using the term "Wild West" to

describe his show. Additionally, Col. Cody had the sheriff seize, under a writ of

replevin, the Indian ponies, wild steer and "untamed stage coach" belonging to

Doc. Carver. Doc, with the assistance of Charles Green, was able to post a bond which permitted the show

to go on. To make matters worse, however, Cody's cowboys were staying in the Southern Hotel, while

Doc. Carver was in the St. James across the street. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch described the situation:

The Cody cow-boys gathered on the sidewalk west of the Southern hotel, were discussing the situation in the

beautiful vernacular of the southwestern plains, when word was brought that the injunction papers had been

served upon Dr. Carver, who thereafter had gone to the St. James hotel. The knowledge that the leading

gentleman of the other combination was available right across the road caused a commotion among the

Cody adherents, and their leading spirit, Buck Taylor, the king of the cowboys, at once expressed a determination to call upon Carver. Taylor is a very big and

muscular six-footer, whose fighting powers and personal beauty are gretly enhanced by the red shirt and embroidered sombero which he weats, and when the newsboys and

bootblacks who had gathered to simply look at the wild Westerners, discovered that there was a prospect of the

enactment in real life of a dime novel episode, they held their breath and excitedly awaited the gory denouement. Buck Taylor's determination to hunt Carver in

the St. James rodunda was no sooner announced than he made a start to cross the street, but Col. Prentis Ingram [Sic.}, Mr. Cody's manager,

Fred. Matthews, the Rocky Mountain stage driver, and Bill Wolcott, the press agent, leaped upon him and begged him to

desist from his fell purpose. The king of the cow boys was finally induced to abandon his raid upon the St. James, and the

atmosphere was relieved of its sanquinary streaks.

With Cody's flair for showmanship, Buffalo Bill's Wild West was an immediate

success. The show included within its ranks, cowboys, Indians (including Sitting Bull in 1885), Annie

Oakley (1884 through 1901 season), the Deadwood Stage, and a menagerie of horses, bison and other animals. The show performed

throughout the world including before Queen Victoria, King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, and

Kaiser Wilhelm. Indeed, Queen Victoria's first public appearance following the death of

Prince Albert, was at the show. The show provided recreations of the famous battles fought in various

wars. By 1901, the show was at its peak and the money was pouring in faster than

Cody could spend it.

Advertisement for Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders, 1901

In October the Wild West performed in Charlotte, North Carolina. A crowd estimated at 12,000 greeted the show. About midnight, Col. Cody's

train pulled out of Charlotte, heading for its next performance in Danville, Virginia. Danville was to be the final performance of the season

before the great show went into winter quarters. The railroad was a single

track system. On single track systems, railroads depended upon a system of schedules and orders to ensure two trains heading in opposite

directions safely passed each other. The train having lesser priority would be side tracked while the priority train

passed. The orders indicating the prioties and where side tracked trains were to wait were written on onion skin

paper, thus their name "flimsies." On the morning in question, Col. Cody's north bound train, made up of three sections, had prioity over

a south bound freight. Orders were given to the engineer of the freight for him to wait on a siding near Lexington. At about 3:00 a.m., the north bound

train passed and the engineer of the freight

slowly advanced the throttle and pulled his train out onto the main line. It is unknown whether the railroad

telegrapher failed to alert stations upline that Col. Cody's train was in multiple sections or the freight engineer misread the flimsy. In any event,

the freight was pulled out after the first section has passed. The engineer was unaware that ahead of him, speeding northbound at

twenty-five miles an hour, were the second and third sections of Col. Cody's train. The second section bore stock cars holding

110 of Cody's horses, including his favorite saddle horse, "Old Pap" as well as the star ring horse, "Old Eagle." Also in the second section

were the Deadwood Coach mules and Col. Cody's private car. Among the pasengers was Annie Oakley, the show's

star shootist.

Coming around a bend, the freight engineer spotted the headlight of the on-coming northbound train, too late to apply the breaks.

The freight enginer and his fireman leaped from their on-rushing locomotive and disappeared into the darkness, not to be seen

again. Killed in the collision were 92 of Cody's specially trained horse including "Old Pap." Found on top of one of the

wrecked engines was the mangled body of "Old Eagle." All six of the Deadwood Coach mules perished. Alegedly injured was

Annie Oakley. She later blamed the train wreck for her hair turning white. She retired from the show. Cody estimated his loss to be over $60,000.00, in

addition to $10,000 in lost receipts at Danville. It took over a year before the Wild West could go back on the road, but it was not the same.

The train wreck occurred when Col. Cody was deep into money commitments in the development of

Cody, Wyoming. That, his generosity to friends and the fact that

his business sense was less than his showmanship, resulted in increasing debt. Indeed,

Cody presaged the future when he once commented to his partner and the manager of the Wild West Show,

Nate Salsbury:

"When you die it will be said of you, 'Here lies Nate Salsbury, who made a million dollars in the show business and kept it.'

But when I die people will say, 'Here lies Bill Cody, who made a

million dollars in the show business and distributed it among friends.'"

In addition to investments in livery stables and hotels in Sheridan and Cody, Wyoming, he invested in oil companies,

irrigation companies,

a film production company, and herbal remedies ("White Beaver's Laugh Cream, the

Great Lung Healer"). By 1908, the show had merged with Pawnee Bill's show owned by Gordon

W. Lillie (1860-1942). The show was owned one-third by Cody, one-third by

Lillie, and one-third by James Bailey's widow.

Left to Right, Charles J. "Buffalo" Jones, Gordon W. "Pawnee Bill" Lillie, Wm. F. Cody.

Left to Right, Charles J. "Buffalo" Jones, Gordon W. "Pawnee Bill" Lillie, Wm. F. Cody.

Charles Jesse "Buffalo" Jones (1844-1919), although at one time a buffalo hunter, became famous for

preservation of the American bison. One of the founders of Garden City, Kansas, Jones was

appointed as a game warden in Yellowstone Park by Theodore Roosevelt. While serving as warden, Jones was required

to take care of a grizzly that was making a nuisance of himself by rading tourist camps and stealing food. Jones punished the

bear by roping him about one of his hind legs and suspending the bear from the limb of

a tree. He then administered corporal punishment by "caning" the miscreant ursine with a bean pole.

Jones devoted the rest of his life to preservation of animals. He was featured in Zane Grey's

Last of the Plainsmen.

Gordon W. Lillie was orignally a teacher in Oklahoma, and was employed by Cody as

an interpreter for Pawnee Indians appearing in the Wild West show. Lillie left the show to

form his own show.

Cody's debts continued to grow and Cody was forced into a series of "farewell appearances."

Cody borrowed $20,000 from Harry Heye Tammen, publisher of the Denver Post to cover the

cost of printing posters. Forewarned is forearmed. Perhaps, Cody should have been wary of

trusting someone who published a postcard bearing the motto: "Live everyday so that you can look

every man in the eye and tell him to go to _______."

When the show was performing in Denver, Tammen had the show seized by the Sheriff and sold

at a Sheriff's sale. Tammen then, holding the debt over Cody's head, forced Cody to

appear in a circus owned by Tammen. Judge W. L. Walls of Cody, Wyoming, noted that in the last two years

of his life, Cody lost between $140,000.00 and $200,000.00.

Wm. F. Cody at grave of James B. "Wild Bill"

Hickok, 1906

Although Cody was ultimately able to disengage

himself from Tammen's clutches and the circus, an increasingly arthritic Buffalo Bill was

required to continue to appear in various shows, including Miller's 101. In the

end Cody was so weak that he could no longer mount his great white horse McKinley and had to ride before

the crowds in a carriage.

Buffalo Bill, 1913

The above photo was taken in Cody on the

occasion of the visit of the 1913 visit of Albert, Prince of Monaco.

Buffalo Bill, with Albert, Prince of Monoco, 1913

Prince Albert had come to

Wyoming on the invitation of the artist A. A. Anderson (1847-1940) who owned the Pallette Ranch on the

Greybull River. The two had known each other from when Anderson was studying art in

Paris. In Paris, Anderson was the founder of the American Art Club on Boulevard Montparnasse.

Anderson was appointed by President Roosevelt as the first superintendent of the

Yellowstone Forest Reserve after Col. Anderson removed

"rustlers, convicts and desperados" from Jackson Hole. In addition to being a personal friend of

President Roosevelt, Anderson was a friend of Col. Cody. Anderson designed the main lodge building for

Pahaska, Cody's hunting lodge on the Cody Road to Yellowstone. Anderson, however, because of his

stand relating to grazing in the Forest Reserve, was not especially well liked by woolgrowers. The

Meeteetse News commented,

"Mr. Anderson can by a single stroke of his diamond-bedecked hand put out of

existence that noble animal that clothes his unclean body." The reference to "unclean body" is perhaps an

allusion to rumored activities in his two-story cabin near present-day Anderson Creek.

It has been alleged that Anderson had models who posed

au naturale. Needless to say, Anderson took

offense and sued, ultimately obtaining an apology. Nevertheless, the rumors live on in the

names of Eleanor, Betty and Vivian Creeks which supposedly bear the names of three of

the models. Supposed activities within the cabin also gave rise to the name of nearby Warhouse Creek.

Early cartographers, in a moment of politcal correctness, allegedly cleaned up the name of the

creek. Certainly, Anderson's lifestyle would not endear himself to local sheepherders. In Europe, Anderson

gadded about the Mediterranean in his steam-powered yacht. The rainbow colors of his pallette found

their way into his attire. In Venice he appeared attired in a black cape lined with crimsom satin.

A damask scarf made with gold threaded fabric and a slouch hat with tassels completed his outfit.

Writer Charles Warren Stoddard was besmitten by Anderson with Stoddard having visions of the two sailing off

together in the steam yacht. But then Stoddard was frequently besmitten by other men. His alternative life was such

that it would have brought shame to writers such as Oscar Wilde. The only thing that came of the

vision were voyages in a gondola through the canals of Venice where the two talked of literature, an invitation to dinner for Stoddard and his

companion, Francis Davis Millet, at the Danielli, and later a visit to Anderson's Paris home. The home reminded

Stoddard of the Arabian Nights.

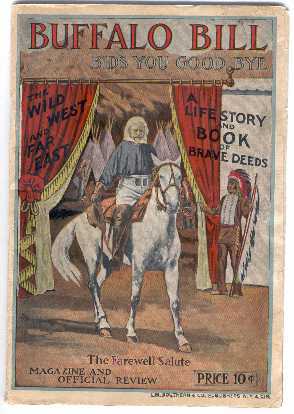

Cover, Souvenir Program, Cody's Farewell Tour, 1910

Cover, Souvenir Program, Cody's Farewell Tour, 1910

On January 10, 1917, in debt and pennyless, Cody died at the home of

his youngest sister, May Cody Decker, in Denver. The day before his death he was

baptised as a Roman Catholic. Condolences cames from all over the world, including messages from

President Wilson and King George V and Queen Mary. None, however,

were more poignant

than that received from Pine Ridge:

Pine Ridge, SD

January 12, 1917

The Oglala Sioux Indians of Pine Ridge, South Dakota, in council assembled,

resolve that expression of deepest sympathy be extended by their committee

in behalf of all the Oglalas, to the wife, relatives, and friends of the

late William F. Cody for the loss they have suffered; that these people

who have endured may know that the Oglalas found in Buffalo Bill a warm

and lasting friend; that our hearts are sad from the heavy burden of his

passing, lightening only in the belief of our meeting before the presence

of our Wakan Tanka in the great hunting ground.

Attest:

Chief Jack Red Cloud

He was buried at public expense on Lookout Mountain in Golden. There, a grave marker was placed by his brother Elks to honor his memory.

Small bronz markers were also placed by the Masonic Order and by the Grand Army of the Republic.

Col. Cody had been intitiated into the

San Francisco Elks Lodge in 1877, but transferred his membership to Omaha Lodge No. 39 in 1897. When the Grand Lodge met

in Salt Lake City, Cody served as grand marshal for the opening parade. In 1916, Cody visited the

Elks National Home in Bedford, Virginia, and took the residents of the home to the show then playing in

Roanoke and shared a camp meal with

his brother Elks. It was not uncommon for Cody to open the show or provide refreshment to

those less fortunate. At the Chicago Columbian Exposition, when the fair declined a request by

the Chicago mayor that there be a children's day for the needy, Cody declared a "Waif's Day" at the

Wild West show and provided free train tickets, admission and ice cream to 16,000 Chicago children. Shortly after Cody's death,

his Congressional Medal of Honor was revoked, supposedly on the basis that, as

a civilian, he was ineligible. The family refused to return the medal.

Cody's name was restored to the list of Medal of Honor

recepients in 1989. The medal is on display in the William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody museuem in Cody.

Cody Grave, Golden,

Colorado, photo by Bob Betts

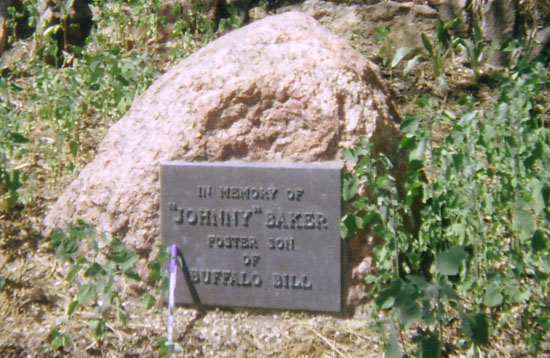

Near the grave, a protege of Cody, Johnny Baker, established a small museum. Baker is remembered at the

museum by a modest rock and plaque set alongside a path leading to a view of telecommunication towers and a transmitter building.

Memorial Stone for Johnny Baker, Lookout Mountain, Colorado.

Size of stone is denoted by

ballpoint pen leaning against plaque. Photo by Geoff Dobson

Cody's will indicated that it was his desire to be buried on Cedar Mountain near Cody, Wyoming.

The Denver Post, published by Tammen who still had a financial interest

in the remnants of the Wild West show, indicated that it was Cody's

oral desire to be buried on Lookout Maintain

overlooking Golden, a desire denied by Cody's friend Zane Gray. Upon his

death, Cody's body lay in state at the Colorado State House. The Wyoming Legislature adjourned all business.

On January 15, Cody's remains were

escorted by silk top-hatted officers of Denver Elks Lodge No. 17 to the Lodge building at the corner of 14th and California where

funeral services were conducted. The caisson was followed by Col. Cody's favorite horse, McKinley, escorted by members of the

National Order of Cowboy Rangers. The Cowboy Rangers wore the red bandanas

of their order. As the casket was lifted from the caisson and carried into the Lodge

building, McKinley seemed restless and attempted to break free from the Cowboy Ranger holding the

horse as if to follow the casket into the Lodge. As the great doors of the

Lodge building closed, McKinley whinnied, broke free and ran to the caisson.

Sniffing and whinnying yet again, the great white horse circled the caisson. The

Cowboy Ranger grabbed McKinley's reins. As McKinley was quietly led away, the horse turned his

head and stared at the doors of the Lodge building through which the casket of his master

had disappeared.

On January 15, Cody's remains were

escorted by silk top-hatted officers of Denver Elks Lodge No. 17 to the Lodge building at the corner of 14th and California where

funeral services were conducted. The caisson was followed by Col. Cody's favorite horse, McKinley, escorted by members of the

National Order of Cowboy Rangers. The Cowboy Rangers wore the red bandanas

of their order. As the casket was lifted from the caisson and carried into the Lodge

building, McKinley seemed restless and attempted to break free from the Cowboy Ranger holding the

horse as if to follow the casket into the Lodge. As the great doors of the

Lodge building closed, McKinley whinnied, broke free and ran to the caisson.

Sniffing and whinnying yet again, the great white horse circled the caisson. The

Cowboy Ranger grabbed McKinley's reins. As McKinley was quietly led away, the horse turned his

head and stared at the doors of the Lodge building through which the casket of his master

had disappeared.

Across the front of the Lodge Room there was a bank of floral tributes from across the nation and from

abroad. The mass of flowers measured fifty feet across and twenty-five feet deep. Within the room, some 1300 Elks, Knights Templar, members of

the Grand Army of the Republic, and Cowboy Rangers gathered. From Wyoming there was Gov. Frank. L. Houx, Senator J. R.

Kendrick, Francis E. Warren, R. S. Van Tassel, H. P. Hinds, C. B. Irwin, Senator Patrick Sullivan, an official delegation from

the Legislature, and numerous others.

From Nebraska came delegations from Omaha Lodge, North Platte Lodge and the Knights Templar. Also in attendance was

the Supreme Boss of the Cowboy Rangers.

Members of the Grand Army of the Republic delivered their service followed by Taps. The Supreme Boss of the

Cowboy Rangers, Albert U. Mayfield, delivered his eulogy. The Lodge secretary called the name of

William F. Cody. And yet twice again the name of William F. Cody was called, but Brother Cody did not respond.

Then to the strains of an old Civl War hymn, Tenting Tonight on the Old Camp Ground, the Hour of Eleven, as it had been for more than

900 years, was remembered; the amaranth and clinging ivy were deposited with

Cody; and the Exalted Ruler, on behalf of the remaining brothers, bade their brother "Good-by -- good-by until the

hour of eleven shall regularly return. Thou art I and I am thou, thy name shall never be

forgotten."

Scene in Denver Lodge Room, Denver Post, Jan 15, 1917, courtesy

Omaha Lodge No. 39, Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks

Scene in Denver Lodge Room, Denver Post, Jan 15, 1917, courtesy

Omaha Lodge No. 39, Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks

Outside, more than 3,000 waited in the bitter cold for over 2 1/2 hours until the doors of the Lodge reopened, so that they might file

past his casket in the Lodge Room. In Omaha, a

Lodge of Sorrows was conducted by Cody's home lodge. There, Tenting Tonight on the Old Camp Ground was

again sung and the Hour of Eleven recalled.

The grave on top of Lookout Mountain was not

yet ready. Thus, Cody's body was kept at the Olinger Mortuary, at the corner of

16th and Boulder Streets, for the next six

months, being reimbalmed six times. A Masonic service was conducted upon his

interment on June 3, 1917.

Sometime later, supposedly, a veterans' organization from Cody

dispatched an expedition to recover Cody's remains and return them to Cody for proper

burial. The expedition, however, allegedly only made it as far as a saloon in Cheyenne.

As a result, however, the City of Golden, surrounded the grave with an iron fence topped with

barbs and took other security measures.

Music this page: Tenting Tonight on the Old Camp Ground

Words and Music by Walter Kittredge (1834-1905)

We're tenting tonight on the old camp ground,

Give us a song to cheer

Our weary hearts, a song of home,

And friends we love so dear.

Many are the hearts that are weary tonight,

Wishing for the war to cease;

Many are the hearts that are looking for the right

To see the dawn of peace.

Tenting tonight, tenting tonight, tenting on the old camp ground

We've been tenting tonight on the old camp ground,

Thinking of days gone by,

Of the loved ones at home that gave us the hand

And the tear that said "Goodbye!"

We are tired of war on the old camp ground,

Many are dead and gone,

Of the brave and true who've left their homes,

Others been wounded long.

We've been fighting today on the old camp ground,

Many are lying near;

Some are dead and some are dying,

Many are in tears.

Many are the heart that are weary tonight,

Wishing for the war to cease;

Many are the hearts that are looking for the right

To see the dawn of peace

Dying tonight, dying tonight, dying on the old camp ground.

Normally, in an Elks Service, the Lodge Organist plays The Vacant Chair, also a Civil War

song. Tenting Tonight was, however, Col. Cody's favorite song and was always played by the

Cowboy Band at each performance of the Wild West. Johnny Baker noted that he had often

heard Col. Cody sing the song. Thus, Ryley Cooper, a writer for The Denver Post explained:

And so the song that was sung about the campfires while the picket men rode their long

journeys on the hurricane deck of a western steed, while the Indians lurked in

the distance, while the sentinels paced their guard, will be the song that will be

sung as a goodby, a farewell to the man who loved the West.

Next page, Cody, Wyoming.

|