Hanna No. 2, undated but estimated to be about 1954, showing abandoned company houses.

As later discussed with regard to other Union Pacific Coal Company towns such as Supeior, coal mining declined in the 1930. There was a rebound during World War II when

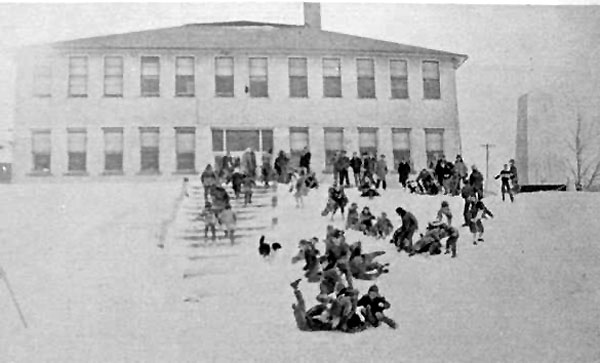

coal was declared to be a critical industry for the war effort. Nevertheless, the town continued. In 1918 the old school was replaced with a two story building.

The elementary school was on the first floor with the second floor occupied by the High School. In 1920, the school adopted its school colors, Orange and Blue.

Hanna School Building, undated.

The Coal Company exhbited its confidence in the town's future. In 1935 it constructed a new 340 theatre, confectionary, and bowling alley. Four years later, it replaced the old

company store with a new building. The theatre was managed by Thomas Lionel Love, Jr. (1906-1970). His father operated a small chain of theatres which included

the theatres in winton, Reliance, and Parco. Lionel, Sr. originally came from England and moved west about 1900. He became a recruiter for the Union Pacific

Coal Company and ultimately became a director of the Hanna State Bank.

Union Pacific Coal Company store, approx. 1949.

As late as 1950, Hanna still had a poplation of over 1300. Ten years later by 1960 it had lost over half its population. The Union Paciic Coal Company mines had all closed. The last to

close was Mine 4A which on March 1, 1954. What happened? The coal had not given out. It was a high-quality low sulphur coal.

On February 15, 1911, the Union Pacific Coal Company was sued by the Federal Government in the United States District Court.The suit was to set vacate the title of the

coal company for much of the Hanna mines. The govenment contended

that the Coal Company had gathered up winos and drunks on Market Street in the LoDo section of Denver and for small sums of money had them fill out

fraudulent claims as "entrymen" for lands in the Hanna area. At the time, Market Street was one of the more disreputable sections of Denver. Originally,

the street was named after Ben Holliday the stage coach king. The street declined and became so bad, that Holliday's family

threatened Denver with suit unless they took his name off the street. In 1913, the Coal Company and the government reached an accommodation.

Thus, much of the coal in the Hanna area held by the Coal Company came from lands leased from the government upon which royalties were paid rather than from

lands owned by the Company.

In 1920

Congress enacted Title 30 United States Code Section 202. Little noticed at the time, the section would have an impact

upon Hanna. The Section provided:

No company or corporation operating a common-carrier railroad

shall be given or hold a permit or lease under the provisions of

this chapter for any coal deposits except for its own use for

railroad purposes; and such limitations of use shall be expressed

in all permits and leases issued to such companies or corporations;

and no such company or corporation shall receive or hold under

permit or lease more than ten thousand two hundred and forty acres

in the aggregate nor more than one permit or lease for each two

hundred miles of its railroad lines served or to be served from

such coal deposits exclusive of spurs or switches and exclusive of

branch lines built to connect the leased coal with the railroad,

and also exclusive of parts of the railroad operated mainly by

power produced otherwise than by steam.

As a result, the history of Hanna is that of the rise and fall of coal mining in Southern Wyoming. The town's fortunes and

prosperity were, by Act of Congress, to a great extent the caboose on trains pulled by steam-powered locomotives and subject to

political winds blowing out of Washington.

As noted, some of the

mines in Hanna were on leased mineral lands rather than on Union Pacific owned lands.

Beginning in the late 1920's, the Union Pacific began experimenting with different types of locomotion including

turbine and diesel electic. The railroad took delivery of its last steam locomotive, No. 844, in 1944. The various

steam locomotives with the exception of Number 844 were gradually withdrawn from service Thus by

1962 with the retirement of locomotive No. 3985, the need for coal declined. Locomotive 844 remains in service.

Hanna, wyoming, 1956.

In 1974, as a result of the 1973 Middle East oil crisis, Congress passed “he Energy Supply and Environmental Coordination Act of 1974.” It provided in

simple terms, among other things, a prohibition of any major fuel burning facility unless

it was determined that such facility had the capability and necessary plant equipment to burn

coal. In 1975 Congress authorized 750 million dollars in loan guarantees for new underground low-sulfur mines.

Northern Indiana Public Service Company had four coal burning electric generating plants. To assure a supply of

low sulphur coal for its plants, it entered into a twenty-two year contract with Carbon County Coal Company, a

partnership between Dravo Coal Company and Rocky Mountain Energy Company, a subsidiary of

the Union Pacific Railroad. Roughly 15 percent of Carbon County's projected output for the contract was to come from federal lands.

Carbon County Coal Company opened new underground mine near Hanna. Other independent mines

opened. The population of Hanna soared to over 2200. This in turn required expansion of the schools and other facilities.

Coal Train loading, Hanna, circa, 1980.

By the early 1980's, the political and environmental winds had reversed and coal was not favored.

In 1984, the Indiana Public Service Commission made use of Northern Indiana's coal fired generating plants

ecomonomically unviable. Northern Indiana notified Carbon County that it would no longer accept the coal. A suit for declaratory judgment was filed in

the United States District Court in Indiana. Carbon County Coal Company counterclaimed for the breach of contract asking for specific performance; that is, that the court

order Northern Inidana to accept its coal.

Northern Indiana defended on, among other grounds, that the contract was in violation of 30 USC Section 202 quoted above and that the action of the

Indiana Public Service Commission constituted a "force majeure." A "force majeure" in legalese is usually an unforseen Act of God which renders performance of a

contract impossible. The appellate court rejected the "force majeur" argument. Regardless of whether the Indiana Public Service Commission takes on the

atrributes of the Diety, Northern Indiana did not appeal the determination of the Commission. In the suit,

the Coal Company noted the impact that the closing of the mine would have on the residents of Haqnna. As to the impact on

Hanna, The appellate Court dismissed the argument stating,that the losses of the businesses and miners in Hanna

were "irrelevant" and that all Carbon County Coal Company was entitled to was money. Thus, the Court upheld a monitary judgment in favor of the coal company in the amount of

$181,000,000. See Northern Indiana Public Service Company v. Carbon County Coal Company, 799 F. 2nd 265 (7th Cir. 1986).

Instant ruination was visited upon the Town and many of the residents of Hanna. The mayor, James Cochrane, noted in a newspaper interview that

houses that cost $60,000 were going for $15,000 if a buyer could be found. The population plummeted so fast that trucks

could not be found to haul away the furniture. One by one, the remaining mines closed. As of 2010, the population stood at 841.

The Hanna School was combined with the schools from Medicine Bow and Elk Mountain. Even with the combination, student population is

approximately half of that it was at its peak. The town's only grocery store, the Food Mart has closed. The closest full-service grocery stores are in

Laramie and Rawlins. By 2012, the Episcopal and Lutheran churches were without pastors. As of 2013, Dingy Dan's remains open. Hope now lies in

a projected coal liquification plant near Medicine Bow.

Next Page, Coal Camps continued, Diamondville.

|