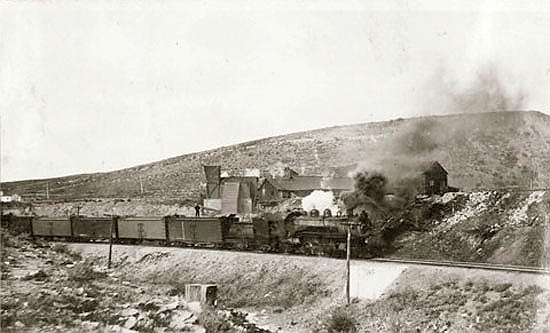

Diamondville Mine, undated. Photo courtesy of

John S. Gilchrist.

Diamondville, two miles south of Kemmerer, another important coal town,

traces its history back to a homestead established in 1868 by Harrison

Church. High quality coal was known to be in the area as a result of the

original governmental surveys undertaken in 1874. Church interested

investors in his Hams Fork Coal Company which ultimately became the

Diamond Coal and Coke Company, a subsidiary of the Anaconda Copper Company.

The Town, itself, was incorporated in 1901 with Scotsman Thomas Sneddon

(1855-1920) as its first mayor. Sneddon became superintendent of the

Diamondville Mine in 1898. Like many of the other miners in the area he

previously had been in the servce of the Union Pacific Coal Co. in Almy near Evanston.

The Diamondville Mine was the scene of several major fires and explosions. On December 26, 1898, a fire

broke out in the mine. The standard method of fighting such fires was to seal off the area and thus

sufficate the fire while operations continued elsewhere in the mine. For six weeks the company battled the

fire. On February 12, 1899, the fire broke out again and two miners, John L. Russell and L. E. Wright were killed by the

"black damp." "Black Damp" is a mixture of unbreathable gases in an enclosed area and mainly consists of

nitrogen, argon, carbon dioxide and water vapor. The gases displaces oxygen in the air.

The term black damp comes from the German dampf, "vapors." "Damp" is used in other mining terms "white damp,"

carbon monoxide; "fire damp," methane; and "stink damp," hydrogen sulfide.

The company was certainly aware of the dangers from coal dust.

In 1900, company superintendent Thomas Sneddon was part of a team investigating another mine

disaster in Utah. As a result he was later quoted as saying,"When I go back to

Diamondville I will have the mine of which I am superintendent prinkled at once, because

it is easier to water the mine than to pack dead bodies out." See Salt Lake Herald,

May 8, 1890, p. 2.

Nevertheless, less than a year later on February 26, 1901 another fire hit Mine No. 1 at the beginning of the night shift.

It was believed to have started from a miner's lamp in the oil room. Initial newspaper reports indicated that some fifty miners and

fifteen horses were entombed when the mine was sealed to extinquish the fire.Because of the belief that

all within the mine had been killed, work was directed to saving the rest of the mine.

Only one man, John Anderson,

managed to escape. Later reports put the number of dead at 32. Most of the men were Ialians, Finns, and Austrians.

Of the crew, three were Americans,

a father and son, Thomas and Everett Simpson. Everett was 17 years old. The third, William O. "Willie" Jarman, had

moved to Diamondville from McAllister, Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma), only two month before.

His wife with their baby was visiting her family at the time. Several weeks before, he wrote expressing his

loneliness and that he did not plan on staying much longer. The company did not have the name of

one miner known only as "Frenchie."

The Deseret News, Feb. 28, 1901, described the scene as families waited outside a barrier for word:

Leaning against the baggage car which contains a score of coffins sent by Underaker S. D. Evans, of Salt Lake, all day long

there has been a knot of sober faced men and grief stricken women, silent and woebegone. Some of

the women bear traces of their headlong flight toward the scene of the horror of the night

previous, as an occasional bandaged head testifies in mute testimony to the blind stumbling in the dark over the railroad

tracks, through the mud, slush and rivulets of water that abound on all sides."

IDENTIFIED VICTIMS OF

1901 DIAMONDVILLE MINE FIRE

FEBRUARY 25, 1901

BATISTA BASSOIA.

EDUARDO ROANI

P. ROANI

JOE FRANZOI

LAWRENCE FRANZOI.

CHARLES ZANOLALI

FIARIANO AVANSINA

ALEX BARIAGNELI

EMANEIO BARTAGNELI

SANTO FORMOLLE

JOE ANDREONI

G. GAHARDI

DEMENICO di FRANCISCO

LARADI ANGELI

ATEGLIO ZEROCAL

WILLIAM JARMAN

FRENCHIE

EMIL AHO

JOHN BANTA

JOHN HEINKINEN

MAT TASANEN

JOHN TASANEN

HUNINING LAPTI

JOEL LAPTI

EVERETT SIMPSON

J. T. SIMPSON

|

On December 1, 1905, the entire night shift of eighteen miners lost their lives in a coal dust explosion. The night shift at the time

was considerably smaller, the work consisting of prepping the face. The San Francisco Call, February 3, 1905, described the shock

of the explosion as being felt all over the town, "rocking buildings so violently that their occupants ran out

into the open." The company, according to the New York Tribune, December 3, 1905, anticipated having the mine reopened in a week.

Mary Harris "Mother" Jones Mary Harris "Mother" Jones

The company was also hit with a number of strikes. There were strikes in 1898, 1899, 1903, and as a part of a state-wide strike in

1908. The company did not restrain itself in its fight against strikers. In the 1898 strike, the company brought

eviction proceedings to remove strikers' families from their company-owned houses. A Salt Lake City attorney who frequently represented

Italians and miners, Wiley L. Brown was arrested in Diamondville for perjury in the cases. At one time,

Brown was a prominent attorney but slowly descended into the depths of being a political and

legal gadfly. He was active in the Republican Party. His legal career ended when his behavior became more and more bizarre. He was arrested in

1904 when the police claimed that he had been "acting in a strange manner of late." He was adjudged insane but released on his

own recognizance on his promise to behave. The following year, he disappeared. His body was found after three weeks in

the mountains. To those who knew him, the circumstances of his mysterious death were not a surprise. The Desert Evening News, November 22, 1905,

explained: "The fact that he was mostly disrobed caused little surprise as he was known to disrobe himself on

occasions and not long ago he was found in the city and county building in a nude condition and was arrested."

In the 1899 strike, the company brought in non-union men who operated the mine. The 200 wives and daughters of the striking

miners marched on the mines and forced the non-union miners to flee. The Saint Paul [Minn.] Globe, December4, 1899, in reporting the

story referred to the non-union men being attacked by a "Mob of Amazons." The next day, over seventy-five deputies appeared on the scene.

A mounted contingent, according to the Salt Lake Herald, "made a dramatic enrance into town. they were all mounted and forming in

columns of two, rode down the main street. The inhabitants ran out of their houses like ants out of an ant-hole to view the

novel sight."

In 1903, the United Mine Workers announced that they were sending Mother Jones to help organize the twenty-one

unorganized coal camps in the state. Superintendent Sneddon announced that the mine operators were prepared for

her appearance and that if she attempted to interfere in any way with the miners or influence them to quit work she would be promptly jailed.

Mother Jones was ordered out of the State of Colorado. In Utah, Mother Jones, age 74,

was held in a quarantine house by local authorities on the basis that she had allegedly been exposed to small pox. In order to

free her, union members burned down the quarantine house. The strike was broken when 182 miners were arrested.

Nevertheless, the Union ultimately succeeded in unionizing the camps in Wyoming. As discussed later, the Union then turned its

attention to Colorado.

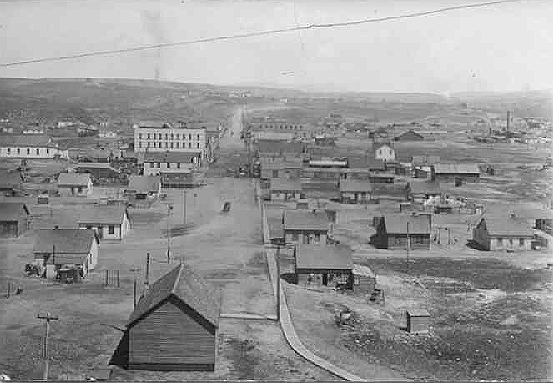

Diamondville, 1913, looking north along Diamondville Ave.

The two-story building on the right-hand side of Diamondville Avenue past the three-story building

is the Mountain Trading Company Building. The Mountain Trading Co. dates to before 1900 and at one time had three

separate stores in the area. Other mercantile companies included the Diamondville Mercantile Co. Additionally, by

1894, the town had the Daly Hotel, named after Montana copper magnate and co-founder of the

Anaconda Copper Co., Marcus Daly (1841-1900). Churches included a Mormon Meeting House and a

Union Church in which the other denominations would meet.

William Fenn's butcher shop, Diamondville, undated.

Fenn had a ranch in the area. He is now noted as having sold a horse, unknowingly, to Butch Cassidy prior to

the Wilcox robbery.

A second "hotel" in the town, not quite as decorous, was one operated by Joseph Kandelhofer. It was described by Justice Sidney Sanner of the

Montana Supreme court:

Diamondville, Wyo., is a mining camp consisting largely of Italians and Austrians, and there

one Joseph Kandelhofer maintains a “boarding house”; this place has two stories, and on the

ground floor are a barroom, leading off from which is a hallway with doors on each side, and

further on a dining room; the doors leading off from the hallway give entrance to a wineroom

and to bedrooms; the wineroom is a dance hall, and the bedrooms are occupied by miners who

lodge at the place; girls and young women were employed there whose principal duties were to

dance with men in the wineroom, drink with men at the bar, and otherwise “entertain” the men

who frequented the place, during all hours from 7 p. m. to 8 a. m.

State v. Reed, 53 Mont. 292, 163 P. 477 (1917)

Justice Sanner continued, noting that evidence "tends to show that the place was not one where a girl could live

for any lenth of time and be respectable." Kandelhofer's facility was closed by the town as a

"public nuisance."

Diamondville Ave, looking north. Photo courtesy of

John S. Gilchrist.

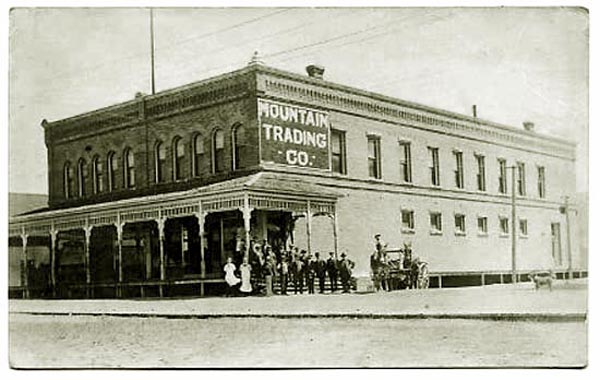

Mountain Trading Company Building, approx. 1914.

Mountain Trading Company Building, August 2003, photo by Geoff Dobson

In January 2003, the Town Council, concerned with asbestos, voted to demolish

the building which had been empty for many years.

The building was torn down in December 2003.

Sneddon family, undated. Photo courtesy of

John S. Gilchrist, whose mother Elizabeth Sneddon is depicted in the photo.

The Sneddon family home is the white house located on the right in the next photo.

Diamondville Mine Buildings. Photo courtesy of

John S. Gilchrist.

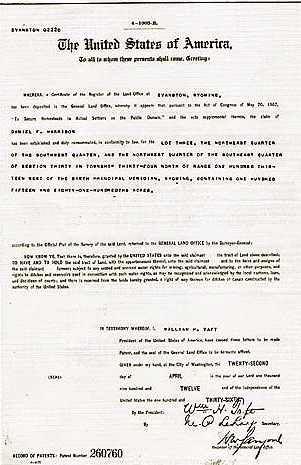

Land Patent in favor of Daniel F. Harrison

As in the instance of the formation of the Union Pacific Coal Co., discussed on a

preceeding page, old fashioned greed came into play. Commencing in 1894,

Sneddon and Daniel F. Harrison began a scheme to

acquire over 2,000 acres of the coal lands by having strawmen file for homestead on the coal lands. Homestead

could be claimed only on non-mineral properties. Each of the applcations for

homestead were accompanied by false affidavits from Sneddon that he was acquainted with the

property and there were no minerals of value on the lands. After government patents were obtained the

properties were transferred to the Company with the patentees being paid $500 each for their cooperation.

A similar scheme was used by the Cambria Fuel Company in Cambria,

which required employees to apply for homesteads which were then conveyed to the Company. Commencing

about 1917, the Government brought actions to set aside over 34 patents on the basis that they were

based on fraud. Twice the action wended its way to the United States Supreme Court which in 1921 ruled against the

company. Justice Van Devanter explained the basis of the lawsuit:

This was a suit by the United States, against an incorporated company

engaged in coal mining, to regain the title to about 2,840 acres of

land in Uinta county, Wyoming, theretofore patented to Thomas Sneddon

and Daniel F. Harrison, and by them conveyed to the coal company. The

patents, thirty-four in number, were issued under the homestead law

upon what are called soldiers' additional entries. The applications

for the entries were made at various dates beginning with May 1, 1899, and

each application was accompanied by an affidavit, by either Sneddon or

Harrison, stating that he was [233 U.S. 236, 238] well acquainted with

the land, had passed over it frequently, and could testify understandingly

about it; that there was not, to his knowledge, any deposit of coal or

other valuable mineral within its limits; that it was essentially

nonmineral, and that the application was made with the object of securing

it for agricultural purposes, and not of fraudulently obtaining title to

mineral land. Mineral lands, including coal lands, are not subject to

acquisition under the homestead law (Rev. Stat. 2302, 2318, 2319,

2347-2351, U. S. Comp. Stat. 1901, pp. 1410, 1423, 1424, 1440, 1441),

and these affidavits were made and submitted as proof that the character

of the lands applied for was such that they properly could be acquired

under that law. The land officers accepted the affidavits and the

statements, therein as true, and allowed the entries and issued the patents.

The bill charged that the affidavits were false and that the entries

and patents were procured in the execution of a fraudulent scheme to

acquire known coal lands under soldiers' additional homestead entries.

The mine closed in 1928.

Music this page:

Hard Times, Come Again No More

by

Stephen Foster

Courtesy Horse Creek Cowboy

I.

Let us pause in life's pleasures and count its many tears

While we all sup sorrow with the poor;

There's a song that will linger forever in our ears;--

Oh! Hard Times come again no more.

CHORUS

'Tis the song, the sigh of the weary;--

Hard Times, Hard Times, come again no more.

Many days you have lingered around my cabin door;

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

II.

While we seek mirth and beauty and music light and gay

There are frail forms fainting at the door;

Though their voices are silent, their pleading looks will say--

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

(REPEAT CHORUS)

III.

There's a pale drooping maiden who toils her life away

With a worn heart whose better days are o'er;

Though her voice would be merry, 'tis sighing all the day--

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

(REPEAT CHORUS)

IV.

'Tis a sigh that is wafted across the troubled wave,

'Tis a wail that is hear upon the shore,

'Tis a dirge that is murmured around the lowly grave,--

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

(REPEAT CHORUS)

Next Page: Oakley.

|