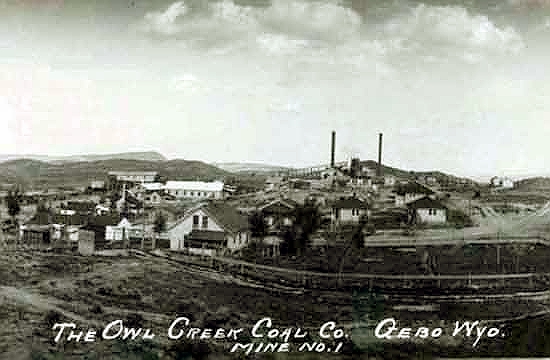

Gebo, 1920's

With the arrival of the railroad in the Thermopolis area, the Owl Creek Coal Company was formed to exploit

coal in the area north of Thermopolis. The mining claims were patented to numerous individuals commencing about 1906.

It soon came to the

attention of the Federal Government that the entrymen were primarily were from the New York area and many of whom were bartenders who

had designated Samuel W. Gebo (1862-1940), a lawyer, as their agent to act on their behalf pursuant to powers of attorney. There were some

64 different entrymen. The claims were being sold to a group of Long Island, New York, investors headed by Lawyer Wilberforce Sully, Lawyer

Patrick T. Wells, Samuel W. Gebo and George W. Daily, a law clerk for Sully. Sully was the owner of two

malting works in New Jersey. The claims were then conveyed to the Owl Creek Coal Company and others by Gebo. Thus was formed the Town of Gebo.

Gebo was located about 11 miles north of Thermopolis.

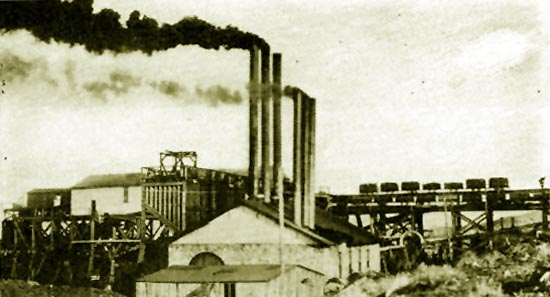

Gebo Tipple and Boiler House, 1913

The federal government brought criminal, civil and administrative proceedings against Gebo, Sully, Daily, Wells, Owl Creek Coal Company, and numerous

entrymen. The administrative proceedings were to revoke the mining patents and enjoin the operation of the mines. By 1912, it became apparent that the

government would be successful in closing the mines.

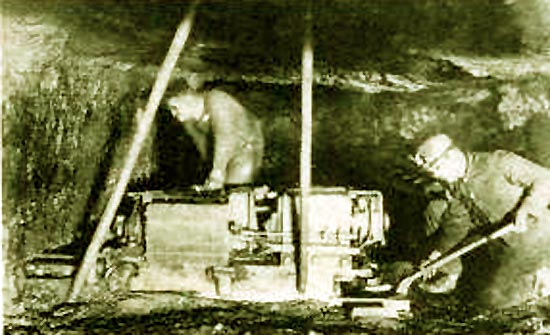

Electric Mining Equipment, Gebo Mine, 1913

The local union intervened on behalf o the

company, writing Senator Warren:

UNITED MINE WORKERS OF AMERICA

Gebo, Wyo.,

February 6, 1912.

Hon. FRANCIS E. WARREN,

Washington, D. C.

DEAR SIR: I have the honor of writing you to-night, being authorized by Local Union

No. 2671 of the United Mine Workers of America to do so. We are very much concerned,

as a body of men, over our work. No doubt you will think it strange that we write to you

over this matter, but I will try to explain, and I have no fears but what you can help us.

We are mining coal for the Owl Creek Coal Co. at Gebo, Wyo. I understand they are having

some trouble with the Government in getting then- patents; in fact, from what we hear,

they can not get them on account of making their first filings illegally. I have no doubt

but such is the case, but it is not for us to say. All we have to say is that we are glad to

work for them, and would like to see them get their patents or a lease or something that

would allow them to continue work. We understand Secretary Fisher is about to make a decision on their filings, and have heard it said that they will lose out. In this event we will suffer the most, for if he decides against them, they will be shut down, and we will be thrown out of employment in the dead of winter. There are several hundred people depending entirely upon this mine for a living, and most of them are men of families. It will be a serious thing if the mine shuts down, for the work has been very poor for several months and we are barely making a living now. But we don't know where to go, because other places are worse, and besides we have not enough money to move away. Now, we do not want the Government to condone any kind of a fraud for our sakes. In fact, we are glad to see them take the stand they are in regards to some who have been violating the Nation's laws. But we feel that some leniency could be shown. If they can not get a title to their land, can they not get a lease? Or if neither of these, could we not prevail upon Secretary Fisher to postpone his decision for a few months

until the weather is warmer and we are in a better condition to move? It would be useless for

us to write him, for it would have no weight, but he would listen to you and no doubt consider

our conditions. I do not desire to weary you, but trust you will intercede for us, and

you will have the best wishes of the entire community. Hoping you will do your best and

wishing you success, 1 am, Yours, respectfully,

A. H. PETERSON, Secretary Local Union No. 2671,

United Mine Workers of America,

Gebo, Wyo.

Indeed, Secretary of the Interior Fisher did listen to Senator Warren. Congress passed a resolution authorized the mining

property to be leased to the Coal Company. It was a win-win for the Coal Company and the government.

The government received a royalty on each ton of coal mined, the Company stayed in business, and the employees

retained their work.

Nearby were the coal camps of Kirby and Crosby. Gebo was an active

mining camp beginning in 1907 when the first coal was shipped out on the railroad until Mining was discontinued in 1938.

Remains of Gebo Tiipple, Photo by Darvin Jemming

The town was bulldozed down in

1971.,p>

Other coal camps

named after Gebo were located in Montana and Kansas. Gebo, Montana, settled in 1893-94 and locally referred to as

"Poverty Flats," was later renamed Fromberg.

The town of Frank in the Province of Alberta, Canada was, however the most famous coal camp established by Sam Gebo. Its fame

was achieved as a result of a tragedy. The tragedy ultimately caused the financial undoing

of Sam Gebo. Frank was established in 1901, and was named after Gebo's partner in the

Canadian-American Coal and Coke Company,

Henry Lupin Frank from Butte, Mont. It was the first coal camp on the eastern

side of the continental divide in the province. Sam Gebo moved with his family to

Blairmore, a town three miles from Frank. In late April 1903, there were several days of rain in

Frank, followed by a freeze. H. L. Frank, himself, was absent from the scene. He

was in Paris attempting to sell the venture to a French consortium for $1,500,000.00.

The mine was in a mountain known to the whites as "Turtle Mountain" and to the Indians as the "Mountain that Walks." The mine was

regarded as more profitable than many other mines because its rooms along the

face were larger than normal. There were fewer pillers. Thus, more coal could be

recovered. In the mine, the miners became acclimated to frequent tremors that shook the mine. Indeed,

the tremors made the work easier. The tremors would knock the coal off the

face so all that was required would be to shovel the coal into

the trams.

In the early morning hours of April 29, a night crew was working the face.

On the edge of the sleeping town was the home of the Alexander Leitch family.

Alexander, his wife Rosemary, and the seven children, four boys and three girls, were fast asleep in their beds.

On the Canadian Pacific, the Spokane Flyer was overdue, delayed by snow. A freight train idled on a siding, awaiting the

Flyer which had priority. About a mile down from the town near the Canadian Pacific tracks was the

Poupoure and McVeigh Construction Camp. The general manager, John McVeigh, was in camp. In the livery were Robert Watt and

Francis Rochette. Watt had declined an invitation to stay in the Imperial Hotel that night.

At 4:10 a.m. a large tremor shook the mine. Rock fell from the ceiling and coal from the face. Some of the men ran towards the portal, outside of

which three men loitered. In the Union Hotel, guests were thrown from their beds by the force of what

was regarded as perhaps an explosion in the mine. A hundred miles away, a sound similar to that of

a distant cannon was heard. The engineer of the freight hearing a rumble and fearful of a landslide,

placed the locomotive on full steam and crossed the bridge just before the bridge was swept away. At 4:10 a.m., a 1/2 square mile of the

mountain slid away, carrying an estimated 90,000,000 tons of lime stone down the valley. The lime stone swept away the Leitch house,

the livery, the power plant, the tipple, the fan house, 5000 ft. of Canadian Pacific track, covered the portal to the mine and buried the

construction camp under an estimated 20 to 100 feet of rock. Other houses, knocked off their

foundations, caught fire. At the end of 100 seconds, there were an estimated 76 dead. The number actually killed will never be

known, only 12 bodies were ever recovered. The lists of the dead included only those known to be

in town. Those in the mine who fled toward the portal were killed. Those who stayed were saved only to

find themselves trapped. The miners had to dig a new shaft themselves inorder to get out. Outside, the conductor of the freight and the brakeman, Sid Choquette, began climbing over a

mountain of rock. The conductor gave up in the face of rocks the size of houses. Choquette persevered and arrived on the other side just in

time to flag down the Flyer. The miners within the mine cut a new shaft themselves to escape.

Alexander Leitch, his wife and four boys were killed. In the arms of her dead mother, the youngest of the

three girls was found unharmed. The other two daughters were found alive, both some distance from the remains of the house, one on a

rock, the other on a bed of hay. Perhaps understandably, the French reneged on the agreement to purchase the mine.

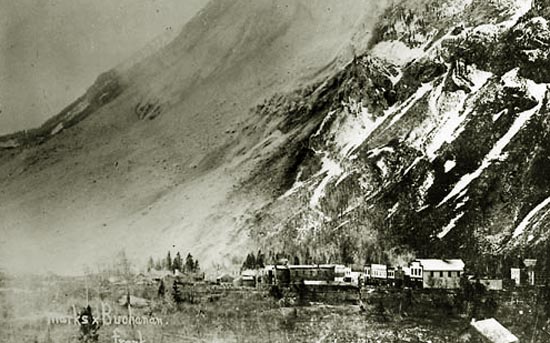

The Town of Frank Alberta, the day after the slide.

Efforts to resurrect the mine at first seemed to succeed, but the slide backed up the river and

began to flood the mine. With the financial stress, H. L. Frank was dead by 1908. In 1909,

Sam Gebo was indicted for filing false land claims with regard to acquisition of Wyoming mineral lands. By 1912, Gebo's company

was in liquidation. Banks and other creditors, including the 1st National Bank of

Thermopolis, the State Savings Bank of Butte, and the Meyers & Chapman State Bank, like so many prairie wolves, fought over

Sam Gebo's financial carcass. In 1913, Gebo left the United States for Guatemala where he developed

a marble quarry. After pleading guilty to the federal charges and paying a $1,500 fine, Sam Gebo returned to the

United States.

On July 10, 1940, in Seattle, Washington, Sam Gebo apparently committed suicide using his gas kitchen oven. Five monthly later, his wife

drowned. With an adverse geological report that the mountain might again walk, the town of

Frank was essentially abandoned by 1917. One business, known as the "brick house," survived. The brick house was inhabited by damsels of the evening. It

ultimately closed and became a target for graffiti. Apparently an embarrassment to the Dominion, it was razed in 1976 as a part of the

centennial celebration of the formation of the Canadian Confederation.

The Town of Gebo,Wyoming, continued to be operated by the

Owl Creek Coal Company and became the largest town in Hot Springs County, even exceeding

Thermopolis in population. Gebo at its peak attained a population of over 2,000. The town had a pool

hall, school, bank, boarding houses, a town band, and outside of town another facility for lonely miners. The pool hall,

however, was a little rough. In 1931, two Serbian miners got into an argument, resulting

in the death of one from lead poisoning. The language used in the pool hall was so bad that

the district judge, Edgar H. Fourt, would not permit it to be translated from Serbian into

English, it being "the vilest stuff that can be used in the slums of America or Europe." Justice

Blume of the Wyoming Supreme Court found the language also to be "extremely vile" and declined to set it out.

Gebo Town Band, undated

The adjacent town of Kirby and the Kirby Coal Company which operated the Crosby Mine took their names from

Kirby Creek. The creek, in turn, took its name from an early Texas cowboy who settled along the

creek about 1878. The Kirby mines closed about 1933 after a fire in the Crosby mine.

Next page, Cambria.

|