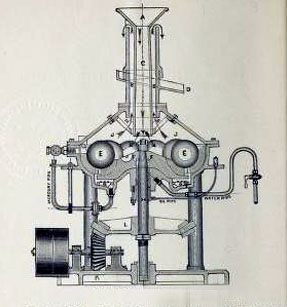

Left: The Crawford Gold Mill, Right. "Cutaway" view of the Crawford Gold Mill

Moreton Frewen ignored the lessons from Wyoming and Wisconsin and with the money from Hyderabad and income resulting from

the death of his brother Richard, Moreton embarked on a series of financial disasters which forever ruined stained the rags which were left of his

reputation. First, he invested in the promotion of the Crawford Gold Crushing Machine.

Left: The Crawford Gold Mill, Right. "Cutaway" view of the Crawford Gold Mill

Moreton Frewen ignored the lessons from Wyoming and Wisconsin and with the money from Hyderabad and income resulting from

the death of his brother Richard, Moreton embarked on a series of financial disasters which forever ruined stained the rags which were left of his

reputation. First, he invested in the promotion of the Crawford Gold Crushing Machine.

In 1892, the Crawford Mill was invented by Middleton Crawford of Ontario and patented in both the United Kingdom and the United States. The mill was supposed to take low-grade ore sush as might be found

in the tailing of gold mines and mechanically grind the ore further so as to

be able to separate "free" gold of the rocks. As can be seen in the cutaway drawing of the mill above,

large steel balls, marked "E" in the cutaway drawing, would grind the rocks, a steam of water would separate the rock pieces and the gold

particles would fall through a mesh and would be further separated through the use of mercury. Crawford had earlier been

a grist miller and thus the machine was similar to that used in milling flour. The mill was tested in several low-grade coal mines

near Belleville, Ontario. A syndicate, the Mechanical Gold Extractor Company headed by Erastus Winman, was formed to manufacture the mills.

At the 1892 Columbian Exhibition, the Gold Extractor Company exhibited its newly patented

Crawford Gold Mill. The machine was supposed to provide a method of extracting

gold from the tailings of mines. Promotional materials for the company quoted Moreton as indicating that the machine

would be ranked with those of Sir Richard Arkwright inventor of the "spinning frame" which enabled the textile industry to be moved

to factories, George Stevenson's steam locomotive, Bessemer with

steel and the inventions of Thomas A. Edison. In his promotions Frewen seemed always

prone to exaggeration. In one promotion of the gold machine, Frewen wrote:

"I venture to think that Mr. Crawford has done more than

merely invent a machine. He seems to me to have discovered a

principle — a principle, not known to science, or if known, then, hith-

erto neglected. It is an evolutionary machine ; one that may rank

in the history of this century with the inventions of Arkwright

and Stevenson of Bessemer and E lison. Of course, the natural

affinity or avidity of mercury for gold has been kuown for centur-

ies past, but Mr. Crawford's machine now declares to the world

for the lirst time this important fact: That by the sub division of

quartz into infinitesimal particles, all tho gold contained can be

released from the quartz and caught by the mercury and that in

short, given atomic pulverization, all gold is "free."

In the meantime, Lord Randolph Churchill's fortunes had taken a downturn. He had been dependent upon his salary first as

Secretary of State and later as Chancellor of the Exchequor. Political careers are somewhat unpredictable. The Tories were

turned out of office. His finances were such that for a while he and his family had to move in

with the Frewens. Lord Randolph was advised by Moreton, among others, to seek his fortune in gold mining in

South Africa. With borrowed funds, Frewen talked his brothr-in-law Lord Randolphinto investing in Frewen's syndicate to manufacture and

promote the machine. It was proposed that Lord Randolph would market the machine to

Cecil John Rhodes. The machine would make usable gold tailings. However, Lord Randolph sought advice from the Rothchilds who led him

to a mining engineer and others. They all advised against involvment with Frewen and his machine. Lord Randolph then withdrew from

Frewen's syndicate and left Frewen and the machine behind. Instead Lord Randolph financed his

expedition with a contract with the Daily Graphic. The paper paid him as a correspondent

£100 per letter describing his quest. His original exploration in Cape Colony proved a failure, but he invested a small sum with

another mining outfit, Rand Mines. Lord Randolph was with the proceeds from that one investment able to repay all

debts and left a substantial trust in favor of his two sons, [later Sir] Winston Churchill and John [Jack} Strange Spencer-Churchill, DSO, TD (1880-1947).

Jack served in South Africa as did Winston and was wounded in the relief of Ladysmith. Winston spent a small portion of his inheriance on

Chartwell Manor. The money Churchill inherited as well as from his writings enabled Churchill to support himself comfortably whilst he wandered in the political

wilderness prior to World War II.

With the failure to sell the machine to

Cecil John Rhodes, Frewen took the machine to Australia.

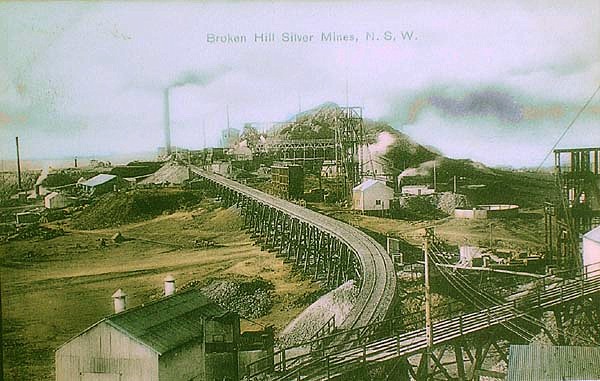

Broken Hill Mine, New South Wales, prior to 1914.

There, he invested in mining in

New South Wales (the Broken Hill Mines). He had hoped to sell his machine.

The machine did not work. The rocks crushed the workings of the machine,

rather than the machine crushing the

ore. The promotion of mining at Broken Hill, however, was sucessful. Broken Hill proved to be the richest

silver mines on earth. It

made those investing in the mines rich. Lord Kintore made millions on the increase in value of

his shares.

Moreton, however, successfully managed, as he had done in the past and as he would in the future, to pluck

disaster out of the jaws of success. He sold his interest in Broken Hill at a large loss in order

to fritter away the proceeds on various half-baked schemes. The result was he had to

beg his brother Richard for money to return home.He proposed to sell his reversionary

inheritance in Innishannon to Richard. Richard declined since he was afraid that

Moreton would again squander away any money.

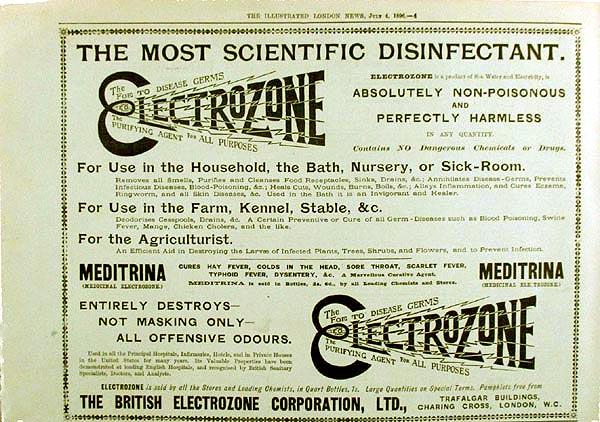

Advertisement for Electrozone,Illustrated London NewsJuly 4, 1896.

Upon his return to the United Kingdom, Frewen devoted money borrowed at high interest rates to the promotion of

"Electrozone," a foul smelling liquid made by applying electricity to sea water. He claimed it was a curative for everythings from

cholera to rotting fish. Frewen was able to convince Lord Roberts to use the substance on the sore backs of draft horses.

He employed the infamous Horatio Bottomley as a frontman for its promotion.

In both the United States and the United Kingdom each of the claims for the curative powers of the

product were found to be false and fraudulent. Bottomley was slippery so that it took many years for the Crown to

make a charge stick.

Frewen for a time resided in the game keeper's house at the

family manor, the allegedly haunted Brede Place, which Frewen's wife Clara had purchase from her brother-in-law Edward about

1896.

Brede Place circa 1906.

Frewen's daughter Clare described Brede in her 1924 autobiography, "Nuda Veritas":

On the eve of our inheritance of Innishannon, it happened

that my mother had enamoured herself of Brede Place, a

fourteenth century ruin on my uncle Edward Frewen’s estate

in Sussex, and he had allowed her to buy it. We must have

been at that time either very prosperous or very imprudent.

We had transferred from Aldford Street to a much larger house

in Chesham Place ; we therefore had three houses, and each

in its different way required considerable upkeep. Brede alone

could absorb a fortune like a bottomless well. It had been

acquired for the sake of its lands by Sir Edward Frewen in

16S0. The land was valuable, but to a man whose ancestral

home was five miles away the house was useless. It was an age

when antiquity counted for nothing. Even the Tudor fire-

places and the oak panelling that shone like varnished tortoise-

shell were not deemed worth removing. The family of a

gamekeeper inhabited two rainproof rooms most of the floors

and all the window panes had long since ceased to be. Swallows

built their nests on the mantelshelves, and the keeper’s boy

knocked nails into the panelling and festooned chains of starling

eggs round the walls. The chapel was a barn, storing grain

and straw. By a miracle the Perpendicular east window-

exposed to all the sea storms — still stood intact. It was this

window which set my mother’s heart on ownership and restor-

ation. Her Americanism with all its appreciation of historic-

tradition spread a full sail ; she was determined and undaunted.

My father, accustomed in his boyhood to birds’-nests among

Brede’s rafters, smiled indulgently and was finally persuaded.

Some small inadequate renovation was attempted. A floor

laid down, a ceiling mended, some window lights adjusted,

a door or two rehinged; and before it was the least bit habitable

the American novelist, Stephen Crane, frail in body, his days

numbered, begged — with a large managing wife— to shelter

beneath Brede’s eaves. He was, so to speak, bowled over

by the sedate grey dignity of this remnant of mediaeval England.

Like Henry James in his cobblestone street four miles away

at Rye, Stephen Crane wrapt himself round in Sussex sea-mist,

and the two Americans were assumed to be more " Sussex ”

even than those who had been bred for generations on its cold

clay soil.

Brede Place undated.

Amongst the ghosts of Brede Place was that of Sir Goddard Oxenbridge who allegedly dined on small

children. The children of Sussex, fearful of being eaten, joined together and tempted

Sir Goddard with a barrel of mead upon which he got drunk and passed out. The children then took a

saw and cut Sir Goddard in half.

With his brother's death in 1896, Frewen inherited the hunting lodge in

County Cork. The income from Ireland provided Frewen with £2,000 a year. An additional inheritance

in favor of Frewen's wife provided another £1,000.

Since Brede Place was basically uninhabitable,the Frewens moved to Innishannon a short distance north of Cork.

There Frewen took delight in creating a fish

hatchery to stock the river with rainbow trout. Clare explained:

My father’s great hobby in those days was a fish hatchery,

his idea being to “stock” the river and make of it the finest

fishing in the South of Ireland. A Scots gamekeeper was

accordingly installed who understood the science of hatching

fish. Into a long shed through raised wood tanks a mountain

stream was deviated, which flowed over the rows of fish eggs

on trays to the small tanks containing " fry,” and thence to

the ponds full of yearlings, and so into the river. There were

salmon as well as rainbow trout spawn. The “rainbow” were

an experiment They gleamed translucently as they crowded

to the surface, or leapt into the air when the sieve full of raw

minced liver was lowered into the water at feeding time. Every

day my father went to look at his fish with almost childish joy.

One night the wooden aqueduct that carried the stream into

the fish hatchery was removed, with the result that all the eggs

and fry were found dead in the morning. Moreover, the

beautiful yearlings in the ponds had been poisoned and were

floating belly upwards. Of all the misfortunes that ever

descended on my father’s head, this was the one perhaps that

hurt him most. It was a devilishly wanton act, as senseless

as it was cruel. My father had regarded his fish hatchery

as a communal benefit. We had our fishing rights, it is true,

but the river belonged to all. This manifestation of hostility

was very surprising on the part of a people by whom we believed

ourselves beloved. Whenever any of us set foot outside our

gate we were greeted with, “ May the Lord bless yer honour,”

and “The Holy Saints preserve you and keep you long!"

with so many compliments in addition that it was difficult to

understand why, as they were so charming to us by day, they

cut down our apple trees at night, uprooted our vegetables

and turned their cows into the garden to trample on the

flowers.- (The Scots keeper has since been murdered, and

our house is a blackened ruin, and so that finally decides their

opinion of us!)

Writer's note: the keeper, Frederick Stenning. was employed by

Frewen about 1899 and also acted as ground keeper and later after

the Frewens moved to Brede Place as subagent. He was shot down by three members of the IRA in the hallway

of the house in from of his wife and childen on March 31, 1921. On June 25, 1921, the

IRA burned down the house along with five others. The IRA contended that

Stenning was a loyalist spy. The Frewens moved to Brede Place about 1907. Clare did not return to

Innishannon for fifteen years. On June 25, 1922, she returned to the remains of her childhood home:

As I drove through Innishannon village, where

I used to know everyone by name in every house and pub and

cottage, people stared at me, hesitated and then smiled and

waved. It reminded me of the scene in “Blue Bird” where

those who had been long dead awakened to life the moment

they were remembered by the living. Innishannon was for me

a dead world, and these people who smiled at me and waved

seemed to be the phantoms of the past, who on the morrow

would all be dead again.

At a turn in the road the motor stopped before a gate and the

driver asked if it would need to be unlocked.

“It will not,” I answered, “it feels more like old times to

scale the wall. ”And so I climbed into the garden that was

full of weeds but smelling like Paradise, because of the syringa

hedges that were in full bloom.

As soon as I came in sight of the house, its hollow walls

standing up against the blue of the sky, I began to tremble

from head to foot with a rigour of emotion. The ghost of a

little girl who had once been me, seemed to be leading me by the

hand and saying, "Don't you remember?” Countless

incidents of the past came surging back. A climbing Gloire de

Dijon rose that had survived the fire still bloomed triumphantly

round Peter’s bedroom window, but for all the tangle of

flowers, and the sunshine of the moment, desolation reigned

supreme. I tried to push through an old gate that had been

thrown across the open doorway, but an uncanny wailing

sound arrested my intention (as also the beating of my heart),

but I discovered to my shame that the banshee was merely the

swinging of the stable door!

Writer's note: Peter, Clare's brother Oswald Frewen.

In the 1930's, Clare travelled to the United States. Crossing the country she visited an Indian Reservation and

stopped by the former site of her father's 76 Ranch just below the Forks of the Powder. There was nothing to indicate

the log mansion's former presence, nothing that is

except an insulator on the ground from the now-gone telephone line connecting

the house to Powder River Station.

In 1905 and 1906, Frewen travelled to British East Africa planning on obtaining a timber

concession. His former manager of the feed lot operation in Superior, Frederick R. Lingham. had made a fortune

shipping cattle and timber from the United States to South Africa and owned his own steamship line.

Unfortunately there was another minor detail. To where the timber was, there was no railway.

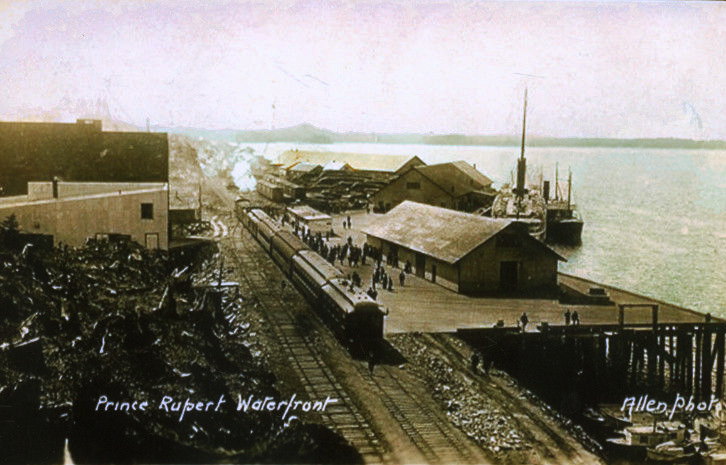

Waterfront Prince Rupert, B.C. undated.

About 1909, Frewen began a scheme for the acquisition of one thousand lots in Prince Rupert. At the time, the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway had commenced construcion of a

fourth transcontinental railway with its terminus in Prince Rupert. The Company had already put in several steamers to connect the

ports of British Columbia with Seattle.

As the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was progressing eastwart across British Columbia, Prince Rupert was to become a port providing

a faster ocean voyage to Asia than going though the Panama Canal. Goods and people would travel from

Britain to Asia via White Star Liners to Canada, then across Canada on the Grand Trunk Railway, and then from Prince Rupert

to Asia. Frewen apparently thought he had an agreement with Grand Trunk's president Charles Melville Hays to purchase 1000 lots in Prince

Rupert.

The railway would, however,

not sell the lots to Frewen upon terms agreeable to Frewen. Frewen sued. He lost both in

the trial court and the British Columbia Court of Appeals. He then with borrowed money appealed to

the Privy Council. Frewen had hoped the agreement could be finalized in Montreal whilst the appeal

was pending. At the time Hays was in the United Kingdom and Frewen was in

New York.

On March 20, 1912, the Privy Council ruled against Frewen noting that

the alleged agreement had not been finalized. and therefore there was no basis for

Frewen's alleged damages. The penultimate sentence was devastating As stated by Lord MacNaghton in Frewen v. Hays, 16 B.C.R. 143:

As regards damages, the company seems to have

followed duly the course prescribed by the agreement, and

there has not been in their Lordships’ opinion any breach of

contract on their part.

It was stated without contradiction that if the plaintiff had

accepted the prices fixed by the company he would have made a

profit of something like 100,000 dollars. The loss of that profit

appears to be due entirely to his own conduct.

Their Lordships will, therefore, humbly advise His Majesty

that the appeal should be dismissed with costs.

Nevertheless, Frewen was undeterred. He still planned to travel to Montreal upon Hays' return to Canada from the United Kingdom and with

his silver tongue enter into

a new agreement. In the early morning hours of April 15, 1912, the ship upon which Hays was

traveling struck an iceberg and sank. Hays was not among the survivors.

Thus, Frewen's hopes and dreams for fortune sank with the Royal Mail Ship Titanic.

No longer able to obtain investors in his schemes, Frewen embarked on the writing of his memoirs and continuing with various articles on "bimetallism."

His memoirs took longer than he expected. He wrote to an old correspondent S.P. Panton in April 1922, that he feared he "left it until it was too late." See

Casper Daily Tribune, April 13, 1922. The letter is significant in that it revealed Frewen's possible involvement in the Johnson County War and the efforts to obtain

federal intervention. Panton was one of the original surveyors of Yellowstone

National Park and later was an editor in Billings and had an interest in economics. Several years earlier, Frewen

had written Panton waxing nostalgic of his days in Wyoming and fishing in the Tongue River. See Buffalo Bulletin, July 27, 1916. In 1922, Frewen suffered

a dehabilitating stroke. He died on September 2, 1922.

Many of Frewen's schemes while a financial disaster for himself, ultimately proved to be successful for others.

Frank A. Kemp who was employed on the "76" became a. successful cattleman on his own. F. W. Lingham was very successful in shipping live beeves abroad to South Africa.

Lord Kimtore an investor in Broken Hill by holding on became a millionaire. Frewen either through impatience or a need for

money always seemed to sell out too early and at a loss. In the instance of the Grand Trunk Railway, he held on too long and lost everything.

Frewen did not finish the autobiography. Much of it contains "filler" of previous articles he had

written relating to bimetallism. The book ends with his memory of Hyderabad prior to 1897 with several paragraphs

as to Col. and Mrs. Richard Nevill. In which he mis-spells the Colonel's surname and totally omits the forenames of

both. He refers to the Colonel as "General." The two later died within one week of each other. The Colonel

is interred in the Hyderabad Roman Catholic Cemetery and Mrs. Nevill in the Protestant. See Vol 5, Chowkidar,

Spring 1990, p. 99.

Clare wrote of her father, "[H]e has a

radiancy about him. Perhaps he has started to hatch rainbow

trout in the rivers of Paradise? Perhaps he has formed a

league of British Imperialist angels to sing Kipling. Perhaps

he has found that God is a Bimetallist."

Frewen's life was perhaps

presaged by the motto on his family arms, "Mutare non est meum", loosely translated,

"It is not of my nature to change."

Next Page, Wild Horses.

|