CATTLE TRAILS IN AUSTRALIA AND THE YUKON

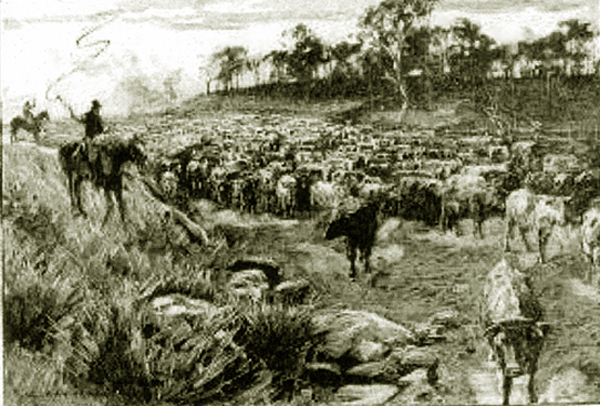

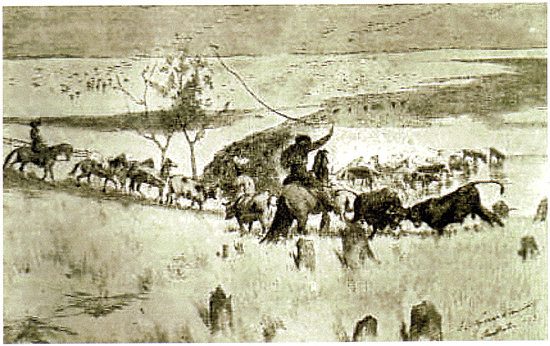

Mustering Cattle in Australia, London Illustrated News, 1850

Several years ago, the writer received an email from an individual in Australia questioning which was rougher, the

Texas Trail described on the preceeding pages or Australian cattle tracks. Thus, it would be neglectful not to

note other famous trails and epic cattle drives. In Australia,"tracks" were established on which

great herds were, as in the United States, driven to shipping points. In 1877,

Nat "Old Bluey" Buchanan drove a "mob" of cattle from Camooweal to the Victoria River connecting

to what was to become the infamous Murranji Track. The Murranji, as a result of the numbers of

drovers killed along its route, was variously referred to as the

"Death Track," the "Suicide Track or the "ghost road of the drovers." The last mob of cattle were taken along the Murranji Track in 1967. The track was

noted for its aridness and passing through an inpenetrable bullwaddy or scrub. And as the early Wyoming

cowboys faced the peril of Indians, so too, the Australian drovers had the danger of unfriendly natives.

Buchanan, a former California 49'er, is also noted from have driven a mob of 20,000 head from central Queensland to

Glencoe south of Darwin in 1880, a distance of about 1000 miles. On a previous trip over the same route,

his cook, while preparing "damper," bread baked over an open fire, was beheaded by natives.

"A Mob of Cattle," 1892, illustration by William Hatherell (1855-1928).

Hatherell was an illustrator for the Graphic as well as leading American publications such as

Harper's.

Drovers trailing cattle along long tracks in Australia goes back to the 1830's. By 1836, large mobs of cattle

were being driven to Melbourne by Joseph Hawdon (1813-1871) with John Gardiner and John Hepburn. By the 1840's

Gungadai in New South Wales was noted for the

quality of its cattle and as a center for stock trading. Early drover, Charles MacAlister visted the town in

1846 and recalled, "Everything about the 'Big Flood' town, except the business mwn, was as green as a leek." The area around Gungadai was green and fertile as a result of

frequent floods. Gungadai early famous for mining is still a center for cattle breeding. But Gungadai has acheived lasting fame featured in

several poems, a dog, and a "hotel," Lazy Harry's which was noted for the friendliness of its girls, and songs:

"Along The Road To Gundagai," "Lazy Harry's On The Road To Gundagai" (the background music for this page), "Nine Miles From Gundagai," "Where The Dog Sits On The Tucker Box," "When A Boy From Alabama Meets A Girl From Gundagai"

and "Never Been To Gundagai."

The Poem written apparently in the 1850's:

The tracks were also used by freighters hauling wool. In Australia, the freighters were callied "bullockies."

A Bullocky Bill and his Dog.

NINE MILES FROM GUNGADAI

by

Bowyang Yorke

I'm used to drivin' bullock teams across the hills and plains

I've teamed outback these forty years in blazin' droughts and rains

I've lived a heap of troubles through, without a bloomin' lie

But I can't forget what happened me nine miles from Gundagai

"Twas gettin' dark, the team got bogged, the axle snapped in two

I lost me matches and me pipe, now what was I to do?

The rains come down, 'twas bitter cold, and hungry too was I

And the dog shat in the tucker-box nine miles from Gundagai

Some blokes I know has all the luck no matter how they fall

But there was I, Lord love a duck, no flamin' luck at all

I couldn't make a pot of tea nor keep me trousers dry

And the dog shat in the tucker-box nine miles from Gundagai

I could forgive the blinkin' tea, I could forgive the rain

I could forgive the dark and cold, and go through it again

I could forgive me rotten luck, but hang me till I die

I won't forgive that bloody dog nine miles from Gundagai

Gradually because of the sensabilities of Australian "wowsers," i.e. prudes, the poem was

re-written and changed so that the dog "sat" on the tuckerbox. But it makes no sense for a dog to actually sit on

a tucker box. Thus, the story developed that the bullocky, a freighter, had gone for help as a result of the

wagon getting stuck in the mire, the dog loyally stayed and guarded the bullocky's tuckerbox in which he

kept his valuables. An updated and sanitized version was published in the 1920's. Nevertheless, on the road to

Gungadai, someone placed a wooden cutout of a dog on sitting on a tuckerbox fastened to a pole next to a bridge where the

incident alleged happened.

Dog on the Tucker box, five miles from

Gungadai, 1926. Dog on the Tucker box, five miles from

Gungadai, 1926.

During a commemoration of the history of Gungadai, the local local hospital board decided that a proper

memorial was needed and raised the necessary funds. The Sidney Morning Herald,29 November 1932, reported THAT More than 3000

people were present at the dedication of the memorial by Prime Minister Joseph LYons.

In a previous story, The Herald noted that behind

the new monument were the ruins of "Lazy Harry's Hotel." The Hotel is recalled in another Austalian "bush song" written by

Banjo Paterson. Over the years, the Road to Gungadai changed from a rural muddy track to the Hume Highway, the major highway

between Sidney and Melbourne. Gungadai became bypassed as tandum semi-tractors roared by. A few tourists took the exit looking for

Australia's most famous roadside monument. Alas, it was five miles out of town on Snake Creek. To improve business, Some local

businessmen wanted to move the munument into town. After four years of furious debate and a $20,000 (Australian) study, the monument remains in place. In

the debates one lady referred to the argument that the dog stood guard over the tuckerbox as

"shit." Probably, she argued, the dog stood in the road and the bullocky kicked the dog. The

dog had his revenge.

LAZY HARRY'S ON THE ROAD TO GUNDAGAI

Oh we started out from Roto, when the sheds had all cut out.

We'd whips and whips of money as we meant to push about;

So we humped our blueys serenely and made for Sydney town,

With a three-spot cheque between us as wanted knocking down.

CHORUS

And we camped at Lazy Harry's on the road to Gundagai,

The road to Gundagai, five miles from Boonabri;

And we camped at Lazy Harry's on the road to Gundagai.

Well, we struck the Murumbidgee near the Yanco in a week,

And passed through old Narrandera, and crossed the Burnett Creek;

And we never stopped at Wagga, for we'd Sydney in our eye,

And we camped at Lazy Harry's on the road to Gundagai.

CHORUS

Well, I've seen a lot of girls, my lads, and drunk a lot of beer,

And I've met with some of both as has left me mighty queer.

But for beer to knock you sideways and for girls to make you cry,

You should camp at Lazy Harry's on the road to Gundagai.

CHORUS

Well, we chucked our flamin' swags off and we walked into the bar

And we called for rum and raspberry and a shilling each cigar;

But the girl that served the poison, she winked at Bill and I,

So we camped at Lazy Harry's on the road to Gundagai.

CHORUS

In a week the spree was over, and our cheque was all knocked down,

So we shouldered our Matildas and we turned our backs on town.

And the girls stood us a nobbler as we sadly said goodbye,

And we tramped from Lazy Harry's on the road to Gundagai.

LAST CHORUS

The road to Gundagai, five miles from Boonabri;

And we tramped from Lazy Harry's on the road to Gundagai.

Meaning of terms used in the song:

"Roto," a small town in New South Wales. It presently has a population of about 50.

"Sheds all cut out:" Shearers at the time went from station to station, often starting in Queensland and working ones way from station to station to the northern district of South Austrail of wlse

southeast to New South Wales and from there to Victoria and then to Tasmania in time for the

annual fleece harvest there. When shearing was "cut out," it meant

Shearing at the particular place had ended.

"Humped our blueys:" Travelled with our swags. A "swag" was a bedroll. Sometime with a heavy blue blanket.

"Three spot cheque," A check for more than £100, at the time a lot of money.

"Wanted knocking down:" The practice of taking the cheque to a public house, handing it to the publican, who used it to cover one's tab. The North Otago Times, 21 September 1901,

"Shearers of Australia," complained, "Formerly, when the sheds 'cut out,' the shearer took his

cheque to the nearest public-house, and 'knocked it down,' i.e., handed the cheque to the

publican, who made the unfortunate man drunk with often drugged liquor, and after two or three days' insensibliity, handed him a few shillings out of, perhaps,

£20! This disgraceful robbery is still practised at bush public-houses."

"Wagga," Wagga Wagga. a town in New South Wales. In the aborigianal lanquage, the plural was made by repeating the

words. "Wagga," a crow. Thus, the town's name meant a place with many crows.

"Chucked our flamin' swags off:" In some published versions of the song, it is written "wags."

"Matilda," a swag, a bluey, a bedroll. Yanks are familiar with the term Matilda as a result of the song "

Waltzing Matilda" which tells the story of a swagman (hobo) who camped beside a billabong (waterhole). He grabbed a jumjack (sheep) and stuffed it in his

tuckerbag (food sack). The swagman committed suicide when about to be arrested by three troopers (police), not to be confused with bushrangers (road agents).

Two of the most famous Australian bushrangers were Ned Kelly and Captain Moonlite (actual name

Andrew George Scott). Moonlite, the son of an Anglican priest, was a layreader and studied for the priesthood before turning to the life of crime.

Both Kelly and Moonlite were hanged in 1880. His last wish was to be buried next to his companion,

James Nesbitt whom he had met in prison. His wish was finally fulfilled 115 years later when his remains were moved

to Gundagai and reinterred next to Nesbitt.

"Nobbler," a drink. The term is now regarded as obsolete.

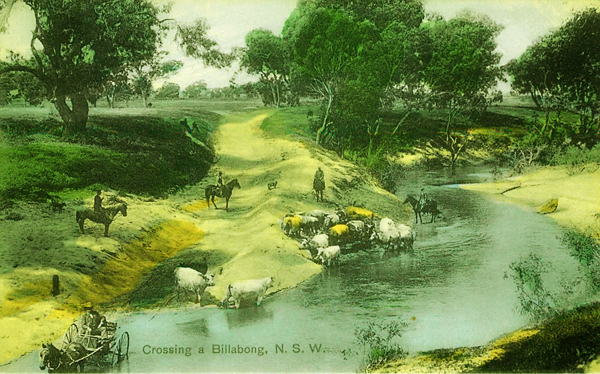

Crossing a Billabong, New South Wales, 1910.

A billabong is a water hole.

The song references the pound. At the time the currency had not been decimalized. There were 20 shillings per pound and 12 pence per shilling.

Thus, coins were in pence (the plural of

penny). In Australia six pence was colloquially a "zack," in Britain, a "tanner." Thus, two tanners made a shilling, a "bob," leading to the old

children's rhime, "Two tanners make a bob, three makes one and six, and four two bob." For a very rough approximation of value from

1900 to present day American dollars, multiply by about 75. Writer's note. The last time the writer and his wife were in Britain, the wife commented to

someone how the currency was so much easier to deal with now as compared to years ago.

The individual did not remember the math that was formerly required with the currency, particularly when some prices were measured in guineas (a pound and a shilling, i.e. 21 shillings).

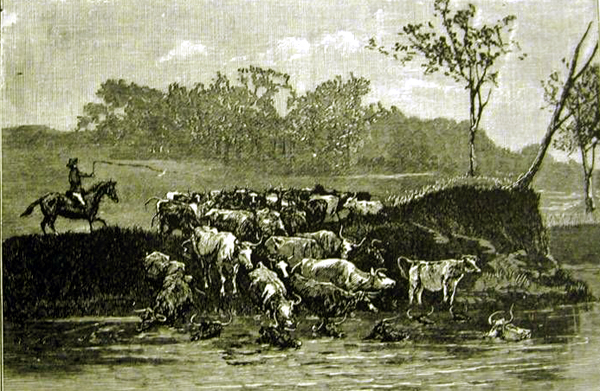

Swimming Cattle, 1888,

Perhaps the two most famous of the Australian tracks was the 1,113 mile long Canning

Stock Route in Western Australia in use from 1911 to 1930 and the 500 km. long Birdsville Track running from

Birdsville, Queensland south to Marree in South Australia. The Canning Route, although less in distance that the United States' Western Trail from

South Texas to northern Montana, was far rougher and more difficult. The route was laid out by Alfred Canning between 1906 and 1910.

Aborigines assisted Canning's survey parties in locating wells. Cooperation was obtained by

placing chains about the Aborigines' necks, forcing them to eat salt until thirst forced the natives

to lead the survey parties to native wells.

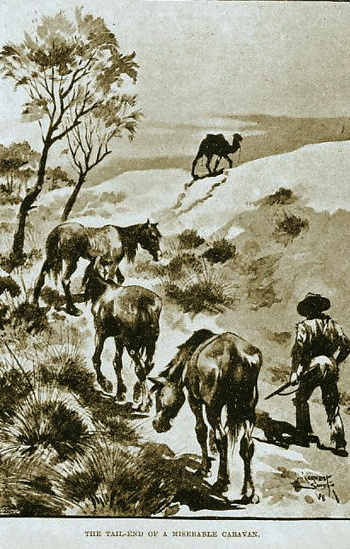

Tail-End of A Miserable Caravan, from

Spinifex and Sand, 1898.

The same technique of obtaining the

cooperation of natives was used by the Honorable David W Carnegie who explored the area in 1896. He kidnapped

natives and in one instance had them drink a particularly briney broth. The area

was so dry that even camels died of thirst and from eating poison plants. Carnegie was the fourth son of the ninth

Earl of Southesk. Carnegie in his 1898 account of his adventures, Spinifex and Sand described the area,

"What heart breaking country, monotonous, lifeless, without interest, without excitement, save when the

stern necessity of finding water forced us to seek the natives in their primitive camps."

Spinifex is the aptly named "porcupine grass" which Carnegie compared to thistle,

"'He who sitteth on a thistle riseth up quickly.' But the thistle has one advantage, viz., that it does not

leave its points in its victim's flesh." Carnegie was killed in Nigeria in 1900 by taking a native poison arrow in his

thigh. All of the drovers on the first drive in 1911 were killed

by the natives. Mobs were generally about 500 head, limited by the number that could be hand watered from water dipped from

wells in canvas bags. Later, drovers would carry with them petrol powered pumps with the fuel and pumps carried

on camels. For those who are daring or foolhardy, the Canning Stock Route may today be traced by four-wheel

drive vehicle. Be forewarned, however, in its 1200 mile length there are no petrol stations. It is

recommended that one take along four, forty-four gallon (Imperial measurement) drums of petrol. If carried all at once,

the weight will bog one down in the sand ridges. Thus, the petrol should be cached along the route.

Following the arrival of the railroad in Marree in 1884, mobs of a 1000 head or more were driven south on the Birdsville Track by

drovers. To the north on the track, camel trains carried the supplies required by large stations. Water along

the track was provided by wells sunk by the South Australian government about every 50 kms. Along the

route might be the occasional "sly-grog" house, more likely a tent, serving the thirst of the

camel drivers and drovers. Sly-grog was booze sold in an

unlicensed facility similar to an American blind pig. In

many instances, the sly-grog was similar to American 40-rod, particularly vile. William Howitt,

an English writer, author of the 1855 Land, Labor and Gold; or, Two Years in Victoria,

described the sly-grog in one the diggings:

"Instead of the splendid home-brewed beer of England, there is rarely anything to be got but

what they call grog – generally a vile species of rum or arrack, vilely adulterated with oil of

vitriol, and therefore the finest specific in the world for the production of dysentery.

Drovers in Austrailia, 1892.

Next Page, Cattle Trails in Alaska and the Yukon.

|