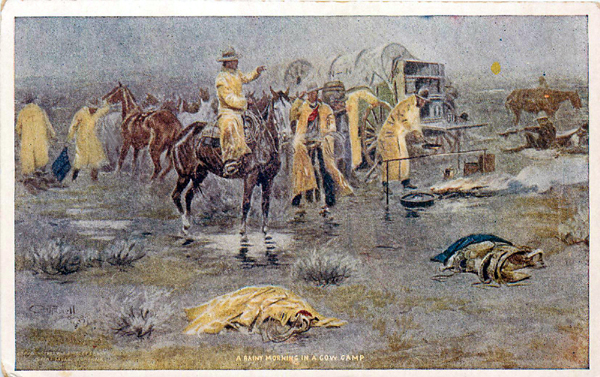

A Rainy Morning in a Cowcamp, C. M. Russell

Rain could be devastating. Jack Flagg recalled that for the first ten days of the Spring Roundup of 1888 on the North Fork of

Powder River it rained continuously, stopping all work. The rivers were out of their banks and it was impossbile to cross them.

As on the trail, there was the cook, a wrangler to tend to the remuda or the herd of horses,

and a night hawk. The cook had the longest hours, Rain or shine, breakfast had to be ready at

dawn, dinner at noon, and supper. In instances where the cowcamp was being moved to follow the roundup,

the cook had to load and unload the mess wagon twice a day.

A Bronc in a Cowcamp, C. M. Russell

Good cooks were hard to get.

Harry Arthur Gant (1881-1967), who rode with the Two-Bar wagon, recalled one cook known as "Cold Bread Sam," because he

baked the biscuits first. Of course, no one called him that to his face, because it would be too

difficult to replace him. See Gant, Harry Arthur, "I Saw Them Ride Away," Castle Knob Publishing, 2009, p. 37.

It was the job of the wrangler, discussed on a subsequent page, to

tend to the remuda, while the night hawk would graze the horses during the night and

recorral them before they were needed in the morning.

Scene in a Two Bar Cowcamp

For discussion of the Two Bar, see Chugwater.

Spring Roundup, Frederic Remington.

As suggested by the horse to the right of the rider, the Grim Reaper often visited a roundup.

Dakota Ranchman Theodore Roosevelt wrote that near where he was then working four men lost their lives:

The definition of good behavior in the cowcountry is even more elastic for a saddle-horse than

for a team. Last spring one of the Three Seven riders, a magnificent horseman, was killed on the

round-up near Belfield, his horse bucking and falling on him. "It was accounted a plumb gentle

horse, too," said my informant; "only it sometimes sulked and acted a little mean when it was

cinched up behind." The unfortunate rider did not know of this failing of the "plumb gentle

horse," and as soon as he was in the saddle it threw itself over sidewise with a great bound,

and he fell on his head, and never spoke again.

Such accidents are too common in the wild country to attract much attention; the men accept

them, with grim quiet, as inevitable in such lives as theirs—lives that are harsh and narrow,

in their toil and their pleasure alike, and that are ever bounded by an iron horizon of hazard

and hardship. During the last year and a half three other men from the ranches in my

immediate neighborhood have met their death in the course of their work. One, a trail boss

of the O X, was drowned while swimming his herd across a swollen river. Another, one of the

fancy ropers of the W Bar, was killed while roping cattle in a corral: his saddle turned,

the rope twisted round him, he was pulled off, and was trampled to death by his own

horse. In Cowboy-Land, Vol. 46, Century Illustrated Monthly, 1893, p. 276, 1888

The fourth was killed in the fall roundup when he was overtaken by an early blizzard. He and his horse froze to death when in

the darkness and gloom they lost their way back to the cowcamp.

"In a Blizzard," from a black and white photo of

a painting by Frank Feller, recreated by G. B. Dobson. Recreated painting copyright 2014 G. B. Dobson.

"In a Blizzard," from a black and white photo of

a painting by Frank Feller, recreated by G. B. Dobson. Recreated painting copyright 2014 G. B. Dobson.

[Writer's notes: Frank Feller(1848-1908) was a Swiss-born British painter and illustrator. The Original painting has been lost and knowledge of it

was limited to a black and white photograph of a print by Henry Graves dated April 1884. We have recreated the original image.

For higher resolution copy of painting, click here.

Feller's most famous painting is one entitled the "Last Eleven." In the "Last Eleven," Feller depicted a Custeresque "Last Stand" incident in the

Third Afghan War when 140 members of the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment of Foot covered retreated Indian

forces at the Battle of Maiwand, July 27, 1880. After the one hundred forty had been reduced to two officers and nine of other ranks, they made a last

stand until their ammunition gave out. They continued with bayonet until they were finally overcome. The only surivor was Bobbie the Regiment's mascot who had accompanied the

regiment when it was transferred to Afghanistan from Malta. The dog wounded and covered with blood made it back to Kandahar where he was recognized.

When the remnants of the 66th were returned to Britain, Queen Victoria presented campaign medals and awards. Included

with members of the 66th received by the Queen was Bobbie. Bobbie was killed two years later when run over by a hanson cab at Gosport, the Home Port of the

Royal Navy. For copy of the "Last Eleven," click here. The Regiment was subsquently integrated into and made a part of

the Royal Gouchestershire, Berkshire and Wiltshire Regiment which has seen duty in the present war in

Afghanistan. British forces in Afghanistan have seen as of March 6, 2014, 453 killed.]

Jacob Bennett (1858-1943), who became a cowboy

at age 14, recalled the death of one of his mess mates on a Spring roundup:

About a month after I was hired on the TC, they started the Spring roundup.

About a month later, all the ranchers'd rounded up all the cattle on that

range and had them on the holding grounds, when the freakiest accident ever

I saw happened. During any roundup, all the men work at top speed to get

the cattle all cut out and the work over before something happens to

stampede the herd, and separate it all out again. You see, all the ranchers

round up every head on the range; then, when they get all the cattle

together, they cut out what belongs to each other, then they can do what

they please with their own cattle.

"Well, during the cutting out, a big old steer quit the herd and went to

running off. Two cowpunchers who happened to be off a ways from the steer,

and in different directions, rode in as fast as they could ride, trying to

cut the steer off and drive it back to the herd. Well, not paying no

attention to each other but keeping their minds on the steer, they ran

together and both fell off. One of them broke his neck in the fall, and

the other fell under the other man's hoss, which stepped in his face and

kicked his head half loose. That was the gruesomest sight ever I expect to

see, the faces they had. Even when I stop to think about it, it gives me

that cold shudders and I have to think of something else.

By age 21, Bennett gave up being a cowboy and returned to Bremond, Texas, where,

among other things he operated a saloon.

Other dangers faced the cowboy besides stampedges and drowning. Major dangers came from lightning and being thrown. In

In July 1882, Augustus H. "Gus" Johnson, the General Manager of the Turkey Track, was killed by a lightning bolt while riding up near the Cimarron.

The lighning set fire to his undershirt, melted his gold shirt stud, and destroyed his hat.

A diamond set in the stud was never found. At the time, he was accompanied by Marcus "Mark" Allen Withers and G. B.

Withers. The plush was burned off Mark's hat but G. B. Withers lost one eye. Mark Withers (1846-1937) came to Texas at age 6 riding a horse all the

way. He first trailed cattle at age 13 and enlisted in the Confederate Army at age 16. Later he made his living by buying cattle to trail

northward on credit and selling for cash. He gave up the trail when it changed to buyying for cash and selling on

credit.

Teddy Blue Abbott noted:

Lots of cowpunchers were killed by lightning, which is known fact. I was knocked off my horse

by it twice. The first time I saw a ball of fire coming my way and felt something strike me on

the head. When I came to, I was lying under old Pete and the rain was pouring down on my face.

The second time, I was trying to get under a railroad bridge when it hit me, and I came to in

the ditch. The cattle were always restless when there was a storm at night, even if it was a

long way off, and that was when any little thing would start a run. Lots of times I have

ridden around the herd with lightning playing and thunder muttering in the distance; when the

air was so full of electricity that I would see it flashing on the horns of the cattle, and

there would be balls of it on the horse's ears and even on my mustache; little balls about the

size of a pea. I suppose it was static electricity, the same as when you shake a blanket on a

winter night a dark night.

The electrical phenomena of which Abbott wrote was known as "foxfire," "St. Elmo's fire, oft noted by sailors.

Cowboys were frequently thrown as a result of

an encounter with holes created by

prairie dogs. George Pattullo, "Glimpses of Cowboy Life in Texas," Photo-Era Magazine, June 1908, p. 294, explained,

[E]ven a night-horse, the surest-footed horse alive, cannot 'negotiate' a dog-hole, and many a good

animal has met his death turning a 'cat'." Teddy Blue Abbott recalled an awful storm:

It took all four of us to hold the cattle and we didn't hold them,

and when morning come there was one man missing. We went back to look for him, and we

found him among the prairie dog holes, beside his horse. The horse's ribs was scraped bare

of hide, and all the rest of the horse and man was mashed into the ground as flat as a

pancake. The only thing you could recognize was the handle of his six-shooter. We tried to

think the lightning hit him, and that was what we wrote his folks down in Henrietta, Texas,

but we couldn't really believe it ourselves. I'm afraid it wasn't the lightning. I'm afraid

his horse stepped into one of them holes and they both went down before the stampede.

A Turkey Track cowboy "Heavily Thrown." Photo by E. E. Smith, 1908.

"Here lies poor Jack; his race is run;

No more this range he'll ride:

At last he's got a steady job

Beyond the Great Divide."

The Cowboy's Grave

In the 1891 Northside Spring Roundup [the northside of the Yellowstone in Montana], a 23 year-old Texas cowboy, possibly

orignally from Crockett County, Texas, Charlie Rutledge was riding as a "rep" for the XIT

with the N Bar N wagon. As Charlie was cutting out an XIT steer, his horse fell and

crushed him.

Cutting Out, undated.

An N Bar N cowboy rode 60 miles to Miles City for medical assistance, but help arrived too late.

The night before, besides the campfire, Charlie had expressed remorse that after having left home over his

mother's protestations, that he had neglected to send her money. After all the work wqs

done in the fall, he would return home and see his

mother. There, as the sun rose over

the lonely prairie, Charlie Rutledge breathed his final words,

"I'll see my mother when the work's done this fall."

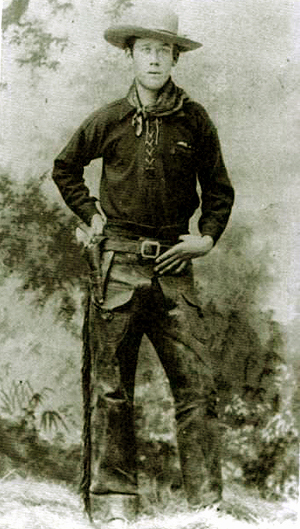

An N Bar N cowboy, Dominick J. White, later wrote two cowboy poems published in the Miles City Stock Growers Journal remembered

Charlie.

Right, Top, D. J. White, Photo by L.A. Huffman, April 1884.

Bottom, D. J. White, Photo by L. A. Huffman, 1887.

The Poem, published in the Stock Growers Journal, was later set to music song finds its origins with the death of Charlie Rutledge, When Work's All done This Fall. The original tribute was also

As with many traditional cowboy songs, the version in the background sung by

Montana Slim is slightly different from the original:

A group of jolly cowboys discussed their plans at ease,

Said one, "I'll tell you something, boys, if you please --

See, I'm a puncher, dressed most in rags;

I used to be a wild one and took on big jags.

"I have a home, boys, a good one you know,

But I haven't seen it since long, long ago.

But I'm going back home, boys, once more to see then all;

Yes, I'll go back home, boys, when work's all done this fall.

"After the roundup's over, after the shipping's done,

I'm going straight back home, boys, ere all my money's gone.

My mother's heart is breaking, breaking, breaking for me, that's all;

But with God's help I'll see her when the work is done this fall.

"When I left my home, boys, for me she cried,

Begged me to stay, boys, for me she would have died.

I haven't used her right, boys, my hard-earned cash I've spent,

When I should have saved it and to my mother sent.

"But I've changed my course, boys, I'll be a better man

And help my poor old mother, I'm sure that I can.

I'll walk in the straight path; no more will I fall;

And I'll see my mother when the work's done this fall."

That very night this cowboy went on guard;

The night it was dark and 'twas storming very hard.

The cattle got frightened and rushed in mad stampede,

He tried to check them, riding at full speed;

Riding in the darkness loud he did shout,

Doing his utmost to turn the herd about.

His saddle horse stumbled and on him did fall;

He'll not see his mother when the work's done this fall.

They picked him up gently and laid him on a bed;

The poor boy was mangled, they thought he was dead.

He opened up his blue eyes and gazed all around;

Then motioned his comrades to sit near him on the ground:

"Send her the wages I have earned.

Boys, I'm afraid that my last steer I've turned.

I'm going to a new range, I hear the Master call.

I'll not see my mother when the work's done this fall.

"Bill, take my saddle; George, take my bed;

Fred, take my pistol after I am dead.

Think of me kindly when on them you look--"

His voice then grew fainter, with anguish he shook.

His friends gathered closer and on them he gazed.

His breath coming fainter, his eyes growing glazed.

He uttered a few words, heard by them all:

"I'll see my mother when the work's done this fall."

When later the words were set to music, Rutledge's penance at not having sent his mother money was omitted and a different final

verse was added:

They buried him at sunrise, no tombstone at his head,

With nothing but a sign-board, and this is what it said

"Poor Charlie died at daybreak, he died from an aweful fall,

And he won't see his mother when the work's all done this fall."

And in distant Crockett County, Texas, a mother waits for her son who will never return.

[Writer's notes: A search of census and genealogical records has been made of Texas. Although several Charles

Rutledge's were found from the applicable time period, only one, a cowboy from Crockett County, was found whose death is

unrecorded in Texas and whose mother had been widowed by 1890.]

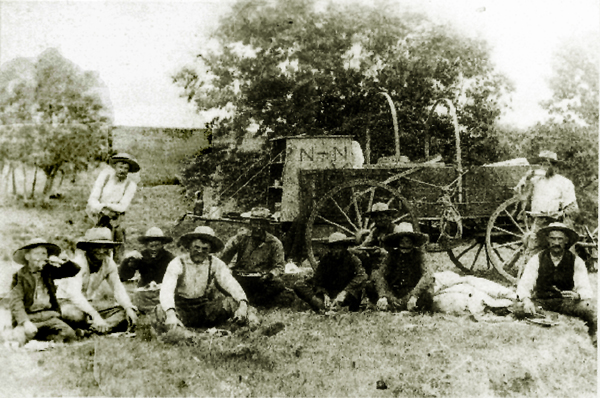

Another cowboy who rode with the N Bar N was C. M. Russell many of whose painting illustrate incidents on the

home range. Two of the usual ranges for the N Bar N were the Big Dry and the Little Dry.

N Bar N Wagon on the Big Dry..

The Big Dry is the area south of the Fort Peck reservoir, north of the Yellowstone, and extending east almost to the

Dakota border. Miles City photographer L. A. Huffman referred to it as the "Big Open," but most

called it the "Big Dry."

In 1904 long after the N bar N had gone the way of all things, Huffman described the N bar N:

“The N-Bar-N was one of the richest outfits on the North Side—plenty of money,

a good range, and no end of dash and ‘go’ in their business.

They handled both horses and cattle. Their horses all came from Washington and Oregon, in great

droves—big, strong, husky brutes. They were wild, too, at first; and it took

mighty husky men to handle them. When the company wanted a thing done,

it was to be done, no matter how many horses were killed. Naturally,

this outfit attracted to its

service the boldest and hardiest lot of men anywhere between

the Yellowstone and the Missouri. No; they were not ‘bad’ men, in any

sense, except that they were merciless on horse-flesh.

But the most of them were perfect dare devils. For instance, Jim's special partner in moonshinin‘

horses, Hank Kusker, used to ride wild steers as a pastime."As quoted by William T. Hornaday, "A True Bear Story", 37 Cosmopolitan Magazine, p. 709 (1904).

Roundup on the Big Dry, 1907. Artwork by

G. B. Dobson based on black and white photo by L. A. Huffman.

A Cowboy's Soliloquy - Poem by Domenick John O'Malley

I am a cowpuncher

From off the North side,

My horse and my saddle

Are my bosom's pride;

My life is a hard one,

To tell you I'll try,

How we range-herded 'dogies'

Out on the Little Dry.

The first thing in the morning

We'd graze upon the hill,

Then drive them back by noontime

On water them to fill,

Then graze them round till sundown

And I've heaved full many a sigh

When I thought 'two hours night guard,'

After night fell on the Dry. >

The next day was the same thing

And the next the same again,

Day-herding those same dogies

Out on the Dry's green plain;

Grazing them then bedding them,

One's patience it does try

When you think 'Now comes our night guard,'

After night falls on the Dry.

They're all right in the daytime,

But our Autumn nights are cold

And the least scare will stampede them,

And then they're hard to hold.

How many times I've 'darned' my luck

When dusk I would see nigh,

And say, 'I wish you were turned loose

E're night falls on the Dry.'

For a large bunch of cattle

Is no snap to hold at night,

For sometimes a blamed coyote howl

Will jump them in a fright,

Then a man will do some riding,

O'er rocks and bad-lands he will fly;

A stampede is no picnic

After night falls on the Dry.

Then should my horse fall down on me

And my poor life crush out,

No friendly hand could give me aid,

No warning voice would shout;

They'd hardly give a thought to me

Or scarcely heave a sigh,

And they'd bury me so lonely

When the night fell on the Dry.

Domenick John O'Malley

D. J. White later changed his

name from White to O'Malley after his step-father named White deserted Domimick's mother, never to be seen again. There is some

question as to the place of birth of D. J. White. He contended that he was born in San Angelo, Texas. However,

when he applied for a pension and had to prove his place of birth, he was surprised to learn

that he was apparently born in New York. The attribution of birth in New York was apparently based on the

1880 census for Fort Keogh which showed that his younger sister Margaret was born in Texas, but he was

from New York. White participated in three trail drives north from Texas for the Niedringhaus Brothers, owners of the

N Bar N.

Music this page: "When the Works All Done This Fall," performed by Montana Slim.

Next Page, Roundups continued.

|