|

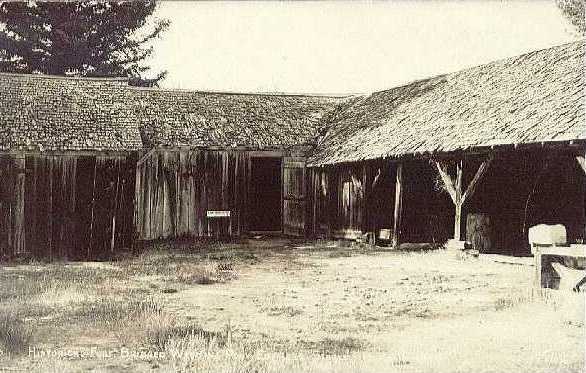

Post Sutler's Stables, Fort Bridger.

The above photo has not been definitively dated, but is believed by the writer to date to about the

turn of the Twentieth Century.

Following the Mormon War, Fort Bridger was mainly associated with the post sutler, William Alexander Carter (1818-1881),

one of the significant characters of Wyoming.

Carter, born in Prince William County, Virginia, came to the Fort with

Albert Sidney Johnston in 1858. His appointment as sutler, however, was as a result of his

friendship with Gen. William S. Harney dating from the Second Seminole War in Florida. Harney, commander of the

Second Dragoons was orginally to lead the expedition against the Mormons, but the Second Dragoons were

left in Kansas to deal with difficulties arising there. Thus, Johnston was assigned. During the

Second Seminole War, Carter was post sutler at a number of forts in East Florida. It was, therefore, only natural that his

old friend, Gen. Harney, would invite Carter to be sutler on the proposed expedition against the Mormons. Correspondence at the Florida

Historical Library also indicates that during the Seminole War Carter became acquainted with a young, newly minted Lt.

William T. Sherman, advancing the lieutenant $14.00. Another young West Point graduate to whom credit was extended was

Edward Otho Cresap Ord, later a Major General. Friendships earned in the Army were lasting. Later at Fort

Bridger, Carter hosted Generals Sherman, Harney, and Ord. Indeed, in addition to appointing Carter as

Sutler for the Morman Campaign, Harney later presented Mrs. Carter, as a gift, his personal private coach which he had imported from

France.

According to a letter dated January 17, 1934, [Florida Historical Library] from the Secretary of the Historical Section, the Army War College, to

Carter's grandson, Edward F. Corson, Carter's involvement with the Second Seminole War began with his enlistment in the Army on July

1, 1836. He originally attempted to enlist underage with the permission of his mother. Young Carter was assigned to Company A, Second U.S. Dragoons for service in Florida.

Among the battles he participated in was one on Feb. 8, 1837, at Lake Monroe, north of present-day Orlando.

Thirteen months after his enlistment, Carter was mustered out on disability on August 12, 1837, at Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida, with a rank of sergeant. In St. Augustine,

troops were housed in a former Roman Catholic

monastery. The monastery was converted to military use by the British in 1768. The British had no use for

a Roman Catholic monastery. It has remained in military use ever since under the British, the Spanish, the American Army, and the

Confederacy. It is now the headquarters for the Florida National Guard. But even before his

discharge, Carter had already begun to show business acumen establishing himself as post sutler at

for the Third Artillery. Sutlers were commissioned to serve forts as well as on the regimental level.

They were, just as a present-post exchange, commissioned to sell goods not provided to the

soldiers by the Army. A letter to Carter from W. A. Brown indicated the types of goods required. The list

included brown sugar, tea, butter, tobacco, molasses, mustard, pickels, pepper, thread, pipes, shaving glasses, plates, forks, and lemon syrup.

Correspondence, however, indicates that his business was spread over all of East Florida, with

subposts at Key Biscayne near present-day Miami, New Smyrna, Fort Hanson near present-day Hastings, and Fort Peyton south

of St. Augustine. Correspondence held by the Florida Historical Society as well as an 1840 deed indicates that Carter maintained his

residence in St. Augustine.

Fort Bridger Stables, 1926.

W. A. Carter W. A. Carter

Life in Florida, at the time, was quite hazardous.

The Second Seminole War (1835-1842) started with the savage murder of the Indian agent and the post sutler at Fort King (present-day Ocala) and the

Dade Massacre in which there was but one survivor. Maintenance of the sutler's store at Key Biscayne rather than on the mainland at

Fort Dallas, may have lessened

the danger of Indian attack, but did not guarantee safety. In 1836, as an example, Indians attacked the

a settlement at New River (present-day Ft. Lauderdale) killing the family of a local justice of the peace. At the time, the area encompassed

by modern-day South Florida may have had a total population of about 60. The Indians then turned

their attention to the lighthouse on Key Biscayne. The lighthouse was tended by an assistant light keeper, John Thompson and

an elderly slave, Aaron Carter. The name of the slave leads to speculation that he may have

belonged to William Carter since slaves took as surnames the names of their masters. Thompson and

Aaron Carter fled into the lighthouse. The Indians set fire to the door as the two fled upwards. The fire ignited

the oil used to illuminate the light. The two, escaping the raging inferno from the oil, fled to the top of the light, cutting

the stairs behind them. Thompson took with him a barrel of gunpowder and a musket. The lighthouse tower acted

as a chimney and, thus, the raging inferno forced the two onto the outside walkway at the top of the light. Bullets from Indian

muskets wounded both of Thompson's feet. Aaron Carter was killed by other Indian bullets. With the heat from

the fire having singed away all of his clothes, Thompson decided to end it all by throwing the gunpowder down the shaft of the light.

The resulting explosion, heard on two navy ships 12 miles away, extinquished the fire but left Thompson trapped at the top of

the tower. The Indians departed. Sailors from the two ships arrived to discover the naked Thompson's predicament. An attempt to get a

rope to the top of the light with a kite was unsuccessful. Ultimately, a ramrod to which twine was tied was shot to the top of the tower.

A rope was tied to the twine which Thompson was able to pull to the top and, thus, effectuate his rescue. The light remained

standing, but engineering investigation of necessary repairs revealed that the original contractors had

cheated the government in the construction.

The Indians burned every settlement along the east coast of Florida south of St. Augustine and

north of the Florida Keys. Even the area around St. Augustine, the walled colonial capital of East Florida, was not

safe. The plantations in the area were abandoned. As late as 1840, the twice weekly stage carrying tourists to the

steamboat landing on the St. Johns River 22 miles from the city gates required a military escort. Notwithstanding the escort, the stage was

repeatedly attacked. In one attack, the stage bore a company of Shakespearian actors. Five passengers were killed.

The Indians were later identified when they appeared in town wearing Shakespearian costumes. Another passenger was killed

in an attack on the stage only two miles west of the entrance to the city. Indeed, the war was the second longest war in

United States history, only the Vietnamese War was longer. The impact of the war was devasting to the fortunes of many of Florida's

rich and famous. Suits for foreclosure were brought against Gen. Joseph Hernandez, one of

East Florida's most prominent planters. Others were forced into bankruptcy. Apparently,

Carter was dependent upon loans to finance his business.

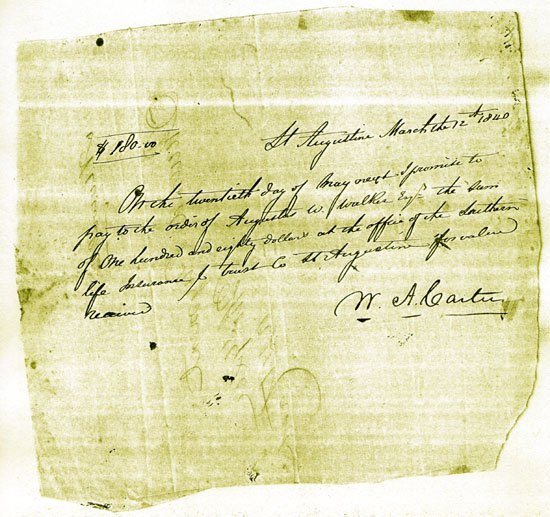

Note from William A. Carter to Augustus W. Walker. Copy courtesy of Florida Historical Society.

The above note was apparently paid by Carter in a timely manner. An undated receipt is attached to the

original. Walker was the Collector of Customs at St. Augustine and an associate with Gen. Henandez. He was

forced into bankruptcy and removed from office. The Southern Life Insurance and Trust Company which had offices in both

East and West Florida became insolvent.

Another creditor, Thomas Butler died. In one lawsuit, it was

contended that Butler's estate was rendered insolvent as a result of the executor's failure to collect debts owed by,

among others, Carter. See, Fairbanks ads. Robb, Alachua County Fla. Superior Court, 1844.

Fort Bridger stables, store and corral, 1926.

The sutler business in Florida, however, was probably less than lucrative. While the position of

a post sutler might be highly profitable at a large post with a civiliam population in the area, the various posts in

Florida were small temporary affairs, with no civilian population. From these small "forts," troops would go out on patrol to keep pressure on the Indians, a tact later used in the

West. The accounts were, therefore, small and, with the soldiers constantly on the move, in some instances

doubtful of collection. In 1840, Carter, as an exammple, wrote to one officer complaining of overdue accounts. Carter enclosed an abstract of accounts due at Palatka from Company "A," 3rd

Artillery, listing some 40 open accounts ranging in size from $1.07 from to $42.07. Apparently, as early as 1840, Carter began considering a

permanent return to Virginia. In May 1840, the Adjutant at Fort Peyton wrote Carter at Key Biscayne reporting that he had heard that Carter

"intended giving up sutting [Sic] for our Regiment and returning permanently to Virginia."

Also adversly impacting on Carter's business in Florida was disease. The largest number of casualties

in the Seminole War was not from Indians, but yellow fever, the "black vomit."

Ninety per cent of those who caught the disease died. Yellow fever was not a respecter

of rank or privilege. The territorial governor Robert R. Reid caught the dreaded disease

and died from its effects. At the time, it was believed that yellow fever was caused by a

"miasma” arising from the fetid decaying vegetation in the swamps. Indeed, the yellow fever

did arise from the swamps, not from a miasma, but from the swarms of mosquitoes which

plagued Florida and St. Augustine in the summer. Indeed, one Florida town, St. Joseph,

in one year, as a result of the disease, declined in population from 6,000 to 400.

While Wyoming honors Chief Washakie and Mrs. Morris in the nation's capital, Florida has a

statute of the inventor of air conditioning. It was intended to assist yellow fever victims in their recovery. With the end of the

war, failing finances, and the need to recover from the yellow fever, Carter returned to Virginia. Gen. Hernandez left the

territory for Cuba.

Pony Express Stables, Fort Bridger.

The above series of stables and buildings were constructed by Judge Carter to store his own

vehicles and for the use of the Pony Express. Adjacent to the stables, as shown in the next picture,

was a butcher shop and meat sorage area. Ice was stored in the tall log chinked building and taken into

the meat storage building.

Stables, looking to the log ice house and the stone meat house on

right. Photo by Arthur Rothstein, 1940. Note installation of new protective roof above the original

roofs on the stable and the meat house.

Connected to the meat storage building was a small mess hall for Cater's

employees (depicted on the next page).

Next page: Ft. Bridger continued,

|