|

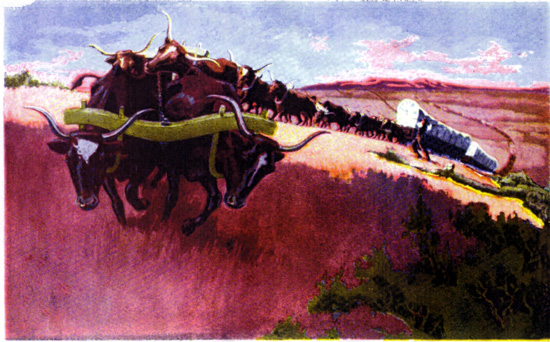

Bull Train, Frontspiece, Hooker, William Francis: The Prairie Schooner,

Saul lBrothrs, Chicago, 1918 .

As will be seen on many of the pages of this website, bull trains similar to those used by

General Johnston continued to be the principal

means of hauling freight in Wyoming until about 1920. Until the coming of the Civil War, Forts Laramie and Bridger remained

principal stops for freighters hauling goods from the "States" to Utah. Col. Cody in his autobiography described

the wagons and trains used in crossing the Plains:

"As a matter of interest to the general reader, it may be well in this

connection to give a brief description of a freight trail. The wagons

used in those days by Russell, Majors & Waddel were known as the "J. Murphy

wagons," made at St. Louis specially for the plains business.

They were very large and were strongly built, being capable of carrying

seven thousand pounds of freight each. The wagon-boxes were very

commodious-being about as large as the rooms of an ordinary house-and

were covered with two heavy canvas sheets to protect the merchandise

from the rain. These wagons were generally sent out from Leavenworth,

each loaded with six thousand pounds of freight, and each drawn by

several yokes of oxen in charge of one driver. A train consisted of

twenty-five wagons, all in charge of one man, who was known as the

wagon-master. The second man in command was the assistant wagon-master;

then came the is extra hand," next the night herder; and lastly, the

cavallard driver, whose duty it was to drive the lame and loose cattle.

There were thirty-one men all told in a train. The men did their own

cooking, being divided into messes of seven. One man cooked, another

brought wood and water, another stood guard, and so on, each having

some duty to perform while getting meals. All were heavily armed with

Colt's pistols and Mississippi yagers, and every one always had his

weapons handy so as to be prepared for any emergency."

The "cavallard" consisted of extra oxen and was sometimes referred to as the "Cavy-Yard."

It enabled a portion of the oxen to

rest. Charles Polk Wells, an early teamster explained:

My day came to drive "Cavy-Yard," and "Dead-Heads" (lazy cattle), as they are called, gave me much trouble straying from the road, first on one side and then on the other. One of thsese exasperating old sinners annoyed me all the forenoon. The more I shipped him and twisted

his tail the slower he seemed to go. Continued hard labor becomes exhaustive, and at times in the

best of families, "patience ceases to be a virture;" therefore, while taking the noon

rest, I studied out a plan whereby "Old Tex" could be made to travel a little faster

that during the morning. Shortly after resuming our journey the old "Dead-Head" began to lag behind. I cut a prickly pear as as

large as a dinner plate, and put it close up under his tail, which closed

down on the thorny appendage with a vise-like grip; the worse the thorns hurt the tighter he held his

tail. He commenced bellowing and dashed in among the loose cattle, causing them

to stampede. The teams also stampeded, some running into the Platte and overturning the wagons and others out on the

prairie also upsetting. Wells: Life and Adventures of Polk Wells, p. 45..

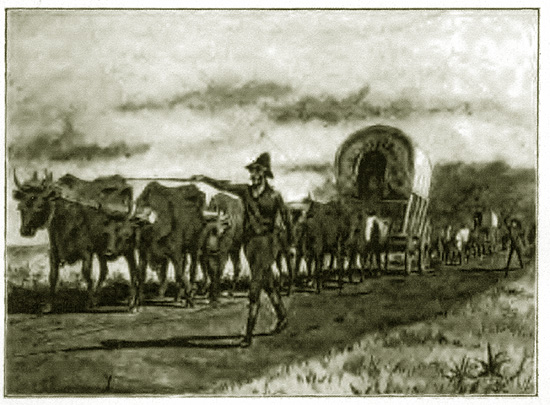

Bull Train, Photo by Thomas Dalgleish .

Col. Cody continued:

"The wagon-master, in the language of the plains, was called the "bull-wagon

boss;" the teamsters were known as "bull-whackers;" and the whole train

was denominated a "bull-outfit." Everything at that time was called an

"outfit. " The men of the plains were always full of droll humor and

exciting stories of their own experiences, and many an hour I spent in

listening to the recitals of thrilling adventures and hair-breadth escapes."

Bull Train, 1860's.

Col. Cody in referring to the "droll humor" was being cicumspect, bull whackers were noted for their colorful lanquage. Polk Wells explained:

[T]here were many stong, well-developed fellos driving teams for a living. Such men will accept small wages

at light work, where board is included, rather than exert themselves for more money; yet teaming is the

hardest work any man ever engaged in--I mean in a moral and healthful sense. The duties of a teamster are not, in themselves

considered laborious, except at short intervals, such as extricating a

wagon from a mudhole, drawing an ox team from the mire, loading and unloading

the train; but the exposure to all kinds of weather, the hard fare he is subjected to, together

wtih the debauch at the end of each trip is many times more injrious to his physical constitution than the work rrequired of him; and so

far as demoralization is concerned, I know of no element more thoroughly calculated to destroy the finer qualities of his character than the

immoral atmosphere always clinging to the freight train, for while it is in motion there is poured into his

ears a continual stream of profanity, and when in camp he hears nothing but vular gests and obscene sories which would

bring a blush of shame to the cheek of a Hottentot or create a wholesome disgust in the

bosom of an Austalian Bushman.Polk Wells, p. 106.

Indeed, the colorful language also continued along with the bulltrains until the 1920's. Bill Gollings,

(1878-1932) recalled as a youth coming across one of the last of the Black Hills bulltrains along the

Belle Fourche:

The bull-whacker seeing that I was interested, said, "Howdy" and asked if I had ever seen

a bull-train or heard a bull whacker swear. To both questions I answered

"no." "Well, kid," he said, "you stay here until I get to the top of this

hill and you'll hear something new." I did not need to be asked to watch

him pull out, the sight was interesting enough to hold my attention. So

I sat my horse and watched him yoke up his eight yokes of oxen and then

move. He certainly told the truth, for, besides calling these sixteen

head of cattle each by name, apparently in one breath, he introduced

one cuss-word after another, until the air was blue with phrases-all new

to me. He finally passed the top of the slope that led down to the river

and thus passed into history as the last bull-team of that section.

Black Hills Bull Train, 1890, photo by J. Grabill

Gollins was a working cowboy whose paintings illustrated

the cattle industry in the northeast portion of Wyoming.

Bullwhacker alongside train, 1860s.

The bullwhacker in the hierarchy of the early west was regard as the lowest of the low. Polk Wells, who started as a bullwhacker and then became a cowboy, then a clerk

in a Trabing Brothers' store in Medicine Bow and laer a notorious outlaw, observed:

The professional scouts look upon the cowboys as being a notch or wo below then in the scale of importance and

the knights of the lariat regard with disfravor the stage drivers; and then "ribbon" manipulators raise clouds of dust and

profanity as they whirl past, throwing dirt and sand into the faces of the mule

driver, who in turn sit bold upright in their saddles on the near wheeler with "jerk-line" in the left and big

blacksnake whip in the right hand and hurry past the ox-teamster without so much as a nod or a mile of brother recognition.

Here, however, the scale of descent comes to a standstill, for the ox-drive, had not a boot black even upon

whom to cast his reproachful looks, and before whom to spread his record of dignity--he occupies absolutely the lowest

strata of western society."

Wells p. 106-107

Nevetheless, just as some cowboys driving cattle northward from Texas established great fortunes, some bullwhackers achieved fame and fortune.

Among then were cattleman A. H. Reel, the stage coach king Ben Holladay, and Chugwater freighters Jack Hunton and Charles Clay.

The "J. Murphy wagons" alluded to by Cody were built in St. Louis by Joseph Murphy.

Murphy, an Irish immigrant, arrived in St. Louis at age 12 and by 1839 had established

himself as a wagon maker. With the opening of the Sante Fe Trail, the Mexican government

imposed a tax of $500 on every wagon load of goods brought into Santa Fe from the

United States. To reduce the effect of the tax, Murphy began to manufacture

huge rigs capable of holding 6,000 lbs. of goods, with a box that was 16 feet long,

4 feet wide and 6 feet high. The rear wheels

were seven feet in diameter with four inch wide tread. Unlike other wagons of the era,

they were fitted with iron axles. The tax was shortly thereafter repealed. Few of the

Santa Fe Trail type wagons were used on the Oregon Trail since they were not suitable

for mountainous areas.

The "Mississippi yagers" referenced by Col. Cody, allude to United States rifles, model 1841. The term "yager" is a

corruption of the name of a German rifle, the Jaeger, from which the Kentucky "long rifle" was

derived. The reference to "Mississippi" comes from the fact that the rifle was

issued to Jefferson Davis' 1st Mississippi Regiment which made effective use

of the rifles during the Mexican War. The rifle was originally manufactured for paper

cartrridges, but with the invention of the minie ball was .54 caliber and later .56

caliber. At the time of which Col. Cody wrote, the model was regarded as

obsolete.

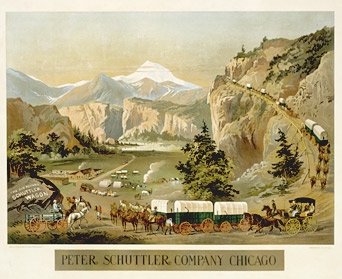

Advertising

Picture for Schuttler Wagons On the Mormon Trail the L.D.S. were partial to "Chicago" wagons manufactured

by the Peter Schuttler Wagon Company of Chicago. Other early

wagon manufacturers included Studebaker and Hiram Young of Independence, Mo., a Black wagon manufacturer who got his

start by purchasing his freedom with the proceeds of ox yokes that he made. As depicted in the

advertising picture, Schuttler also manufactured farm wagons and spring wagons./p>

Some contend that the Mormon War

was a federal victory. It is probably an exaggeration on both sides.

Certainly, federal authority was reinstated in Utah, and equally certainly, territorial governor Young had

no authority to resist his replacement by President Buchanan or to declare

martial law in an attempt to preclude the seating of a new governor. Any

claimed intention of creating an independent state was forever quashed;

yet the Church continued as the dominant political force in the territory and

its "peculiar practice" continued for another two decades.

Actual casualties on the Army side were: 4 died from wounds or injuries, 34 died from

disease including 8 of typhoid and 1 from scurvy. One died from drinking poisonous alcohol at

Fort Bridger.

For his services during the Mormon War, Albert Sidney Johnston conferred the honorary title of "major"

on Bridger. It should be noted, however, that Capt. Stansbury in his report, published in 1855 prior to the

Mormon War, refers to Bridger as "Major." Johnston bled to death as a result of a minor wound at Shiloh April

6, 1862, the same battle in which John Wesley Powell lost his arm.

Next page: Fort Bridger continued, Judge William A. Carter.

|