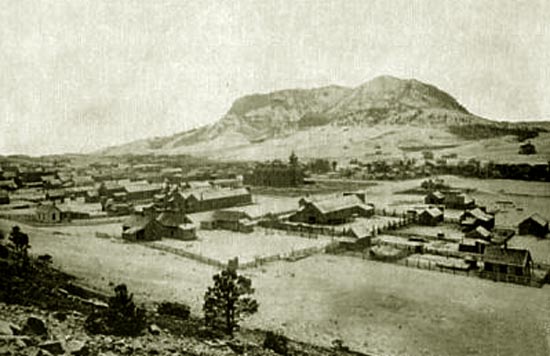

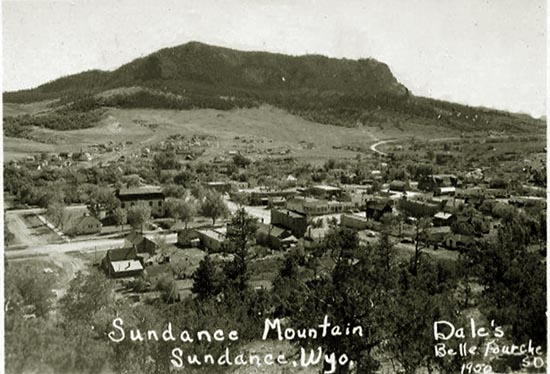

Sundance, 1890's

Sundance, forty-five miles north of Newcastle, is the County seat of Crook County.

The County was organized in 1875 and Sundance established

in 1879 during the Black Hill Gold Rush. The town was laid out by and named by Albert Hoge who initially owned and operated the

hotel and store. The building toward the center background with the

tower is the Courthouse constructed in 1886. See next photo.

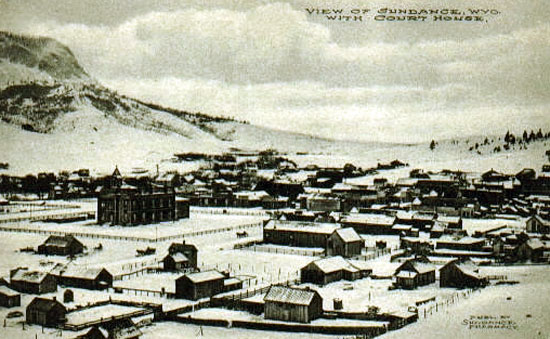

Sundance, undated.

The Courthouse is the large building to the left of center. Behind the main part of the

building is the jail. To the right and across the street, the oblong building with the

false front facing the Courthouse yard is Zane's hotel and Dining Room. Today, many associate Sundance with Harry Longabough, aka, the Sundance Kid. Indeed,

Longabough, in fact, took his name from the small town in the Black Hills of Wyoming.

Longabough, born in New York State, found himself down on his luck near Sundance and

stole a horse belong to the VVV Ranch. Captured by Crook County Sheriff Ryan near Miles City,

Montana, he served 18 months in the Sundance Jail. Following completion of his

sentence he wandered to Belle Fourche, S.D. There he bragged about his experiences in the jail with such bravado that

he earned the sobriquet "Sundance."

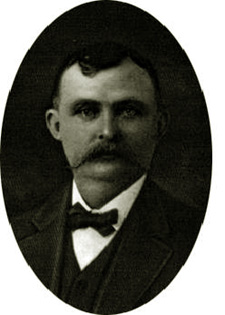

Charles H. Sackett Charles H. Sackett

One of the early settlers in the town was Charles Henry Sackett (1859-1937) who came to town in 1890 and established the leading saloon. There were,

of course, multiple saloons, but most appealed to those interested in cheap drinks. Sackett's saloon had an elaborate bar and

oak furniture. Sackett, originally from Iowa, had been orphaned at age 12 and worked on river boats. He came west to Dakota Territory working on government survey

crews. Later, he worked as cook, stage driver, and messenger until the stage line was put out of business by the

advance of the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad. He then worked as a bartender in Rapid City until moving to

Sundance and establishing his own saloon.

In 1893, a young freshly minted dentist, Will Frackleton, looking to set up practice in Wyoming as a "tooth carpenter," came into

town. In small towns there are, Doc later explained, three was of becoming immediately known: run an ad in the local weekly newspaper, visit the barber shop, or

go to the best saloon in town. The advance ad in the paper did not seem to have been effective. Therefore,

Doc headed off to the saloon attired in what he hoped would be perceived as professional looking garb. The saloon, unfortunately, was

empty except for Charlie Sackett polishing the glassware. From Charlie, Doc learned that most of the

men were watching a boxing match in the hall on the second floor of the fire house. There, Doc discovered that the local banker had set

up a full professional looking boxing ring and was taking on local cowboys with bets on the side. The banker had

taken boxing lessions in Chicago and was polishing off the various challengers. A stranger wearing eastern clothes is immediately pegged as a

"dude." Being called a "dude" ranked, Doc later wrote, "about fourth high in the list of fighting words." "Wyoming was," he said, "still a man's

country, and a dude was considered effeminate and a sissy instead of a financial asset." Frackleton, Sagebrush Dentist, p 17.

The banker, spotting the young dude, challenged his to a fight. Doc demurred, claiming not to know much about the manly art of

self defense. Eventually, Doc agreed to a friendly match the next morning when not many would be around. Doc went back to

Charlie Sackett, gave him a hundred dollars and told him to place it around, betting on Doc to win with a knockout. Charlie agreed to

act as Doc's second.

The next morning when Doc showed up, the place was packed. All had shown up to see the banker whip the Dude. Doc, to feed the flurry of bets Charlie was

making, showed up in his best "dude" outfit, complete with celluloid collar and derby hat. A derby, Doc noted,

was like ordering lemonade in a saloon. For the first two rounds, Doc looked a picture of dispair and impending doom. By the end of the second round all of

Doc's hundred dollars had been bet. The gong rang for the third round, what all believed would be the coup de grāce .

Doc came out looking very tired and groggy. The two touched gloves. The banker winked prodigiously at a ringside admirer. What none knew,

Doc had paid for part of his dental school education by boxing

under the name of "Willie Riley." Doc, in a weak voice observed, "Excuse me, Mister, your shoe is untied." Doc, later wrote:

"It was an old trick, but he fell for it and looked down--a fatal mistake. I stepped in with a right to the solar plexus, a blow new at the time, and a

left to the button. Then I uppercut with a right. Down and out he west.

The crowd had never seen anything like it before. The yelling ended quickly in a long silence. The referee began to count."

Frackelton, p. 19.

As soon as his gloves could be removed, Doc grabbed his shirt, collar, and derby and beat a hasty retreat back to the hotel, leaving

Charlie to collect the bets. Doc was accepted. The sheiff stopped by the hotel to take Doc back to

Sackett's for a drink with the boys, the sheriff telling Doc, "You know, kid, I never did have much use for that guy."

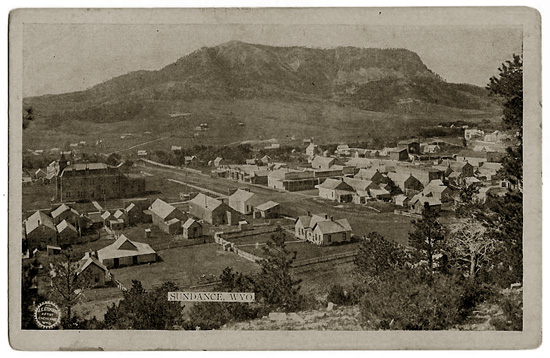

Sundance, 1907. Photo by J. E. Stimson.

Doc Frackelton moved to Sheridan which because of the railroad became the big town in northeast Wyoming.

Charlie Sackett in 1917 foresaw the coming of Prohibition, sold the saloon, and opened the Sundance Garage, an agency for the sale and service of

Dodge Brothers and Hupmobile cars. On Sunday, the Fourth of July, 1937, Charlie Sackett and Dr. J. F. Clarenbach went fishing on Sand Creek.

They had a good catch and abount noon took a break for lunch. In the nearby woods were two hunters from Lawrence County, South Dakota.

One of the shots from the two hunters came perilously close to Sackett and Doc Clarenbach. Doc yelled out to the hunters. Then came another shot.

Charlie's last words were "Doc, I'm shot." Charlie Sackett had an Episcopal service at the Commercial Theatre led by Judge Harry P. Haley.

Doc Clarenbach's Model "A" is now owned by the Crook County Museum.

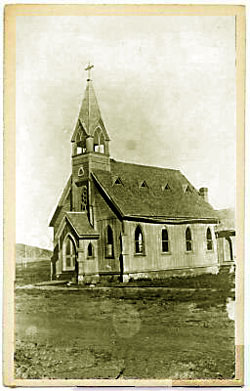

The Episcopal Mission Church of the Good Shepherd.

The Church of the Good Shepherd was constructed about 1889 under the leadership of the Reverend

Charles E. Snavely. The Reverend Snavely following the Spanish-American War was stationed

in Puerto Rico. The Church originally cost $1600.00 but fell on hard times. After the establishment of

Newcastle some 45 miles to the south, services were infrequent. The great distances in Wyoming made pastorial

visits difficult. In 1889, the American Baptish Home Mission

complained that Wyoming was "largely

terra incognita." Julian Ralph in his 1892 Our Great West forcast that the coming of the

railroad to northern Wyoming would "connect these farms with

Christendom." But if the Black Hills were separated from Christendom, the traveling

Episcopal bishops brought Christendom to the farms and ranches. The Right Reverend Anson Rogers Graves described in his 1911

autobiography, The Farmer Boy Who Became a Bishop, his pastorial trip to Horton, a small town midway between Newcastle and

Sundance consisting of a school house and a small general store:

"We drove on up the gorge and over a high divide in the

Black Hills. From there we descended what is aptly

termed Break-Neck Hill. The last time I was on this

steep, narrow road, a great boulder had rolled down

into the middle of the way, and it was with the greatest difficulty

that we got our buggy over and past the obstruction. On we drove

many miles to a lonely ranch nestled in the

edge of the hills. Here we stopped for dinner and found

refined, Church people, who most heartily welcomed us to their home. Again

we drove on northward over the undulating plains until

twetny miles from our starting point we came to a store and not far away a white

school-house in a grove of pines. Two miles farther on we

came to the home of Mr. Cleave, where we

were to say for the night."

The service was given in the school house. Unfortunately, there was no oil for the

lamps. One of the congregants rode out to a nearby ranch for oil. The owners were away and the

house was locked. Outside the small school house a thunderstorm raged. Thus, the service was given in the dark from

memory illuminated only by an occasional flash of lightning outside the windows.

The lightening would have given an eerie appearance to the Bishop who assures us in

his autobiograhy that he nevertheless made all the approriate signs.

Ferenc Morton Szasz, The Protestant Clergy in the Great Planes and Mountain West,

1865-1915, University of Nebraska Press, 2004, gives us the impression that the arrival of a Episcopal Bishop gave in the isolated

parts of the west:

Whenever an Episcopal bishop vistited in full vestments, he

was certain to draw a large crowd. On Daniel Tuttle's arrival in

Rocky Bar, Idaho, a small boy offered to get a bell and

ring it through the town to alert the people, as he had done for a previous

traveling road show the week before. When Episcopal Bishop John

F. Spalding spoke in Rico, Colorado, a miner named

Brownie Lee passed the plate, gun in hand. When one man

dropped in only a quarter, Lee announced,

"Take that back. This is a dollar show."

In Horton, the collection was taken in the dark. Bishop Graves does not tell us how much

was in the offering. At one point, the Church of the Good Shepherd was in danger of defaulting on

its mortgage and being auctioned on the courthouse steps. But in law of foreclosures as in religion there is always redemption. Thus,

the church was saved. Bishop Graves explained:

Here we have a church, which cost sixteen hundred

dollars. It was lost on the mortgage being sold to the

Romanists for one hundred and fifty dollars and finally

rescued from them by our people.

Repairs were then undertaken by the Reverend William Westover of Newcastle who would alternate services between

Newcastle and the hinterlands every other week.

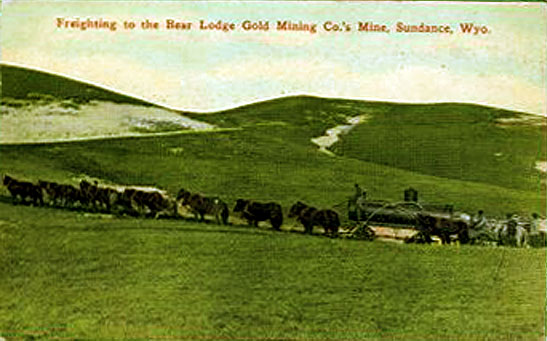

hauling boilers to the Bear Lodge Mining District.

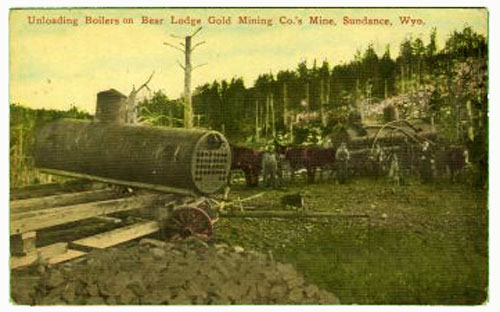

Unloading of boilers at Bear Lodge Gold Mine, Bear Lodge Mining District.

The Bear Lodge Mountains are approximately seven miles north of Sundance. There were two mining districts

in the area of Sundance, The Bear Lodge District in which there was one mine and the Hurricane Mining

District about ten miles north of Sundance in which there were three small placer mines. Gold mining

efforts in the area were less than stellar. The three mines in the Hurricane district, as an example, yielded in

1907 only $600.00 in gold and 9 fine ounces of silver. Other mines in the area included the

Independence mine operated by the Roenna Mining Company of

Tinton, The Copper Prince and the Hutchins Consolidated Gold Mining Company mine. The latter two were each

seven miles north of Sundance.

Sundance, 1950.

Music this page:

THE OLD RUGGED CROSS

Music and words by

The Reverend George Bennard

On a hill far away, stood an old rugged cross,

The emblem of suff'ring and shame;

And I love that old cross where the dearest and best

For a world of lost sinners was slain.

Oh, that old rugged cross so despised by the world

Has a wondrous attraction for me;

For the dear Lamb of God left his glory above,

To bear it to dark Calvary.

In the old rugged cross, stained with blood so divine,

A wondrous beauty I see;

For 'twas on that old cross Jesus suffered and died,

To pardon and sanctify me.

To the old rugged cross I will ever be true,

Its shame and reproach gladly bear;

Then he'll call me some day to my home far away,

Where his glory forever I'll share.

So I'll cherish the rugged cross,

Till my trophies at last I lay down'

I will cling to the old rugged cross,

And exchange it some day for a crown.

Next Page: Sundance continued.

|