Overland Trail Ruts near Guernsey

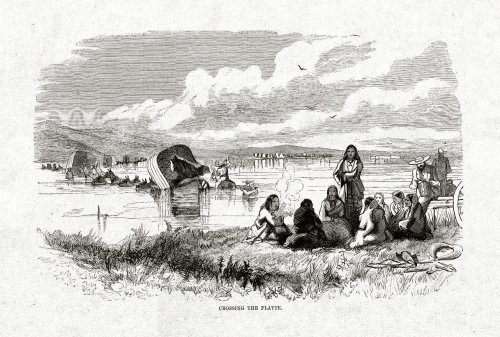

To avoid the tolls levied by the proprietors of the bridges or ferries, many

emigrants attempted to ford the Platte. This was not without danger or peril. Col. William

Thompson in his 1912 Reminisences of a Pioneer wrote of crossing the

Platte in 1852:

At Fort Laramie we crossed the Platte river by fording. The stream, as I

remember it, was near a mile wide, but not waist deep. Thirty and forty

oxen were hitched to one wagon, to effect the crossing. But woe to the

hapless team that stalled in the treacherous quicksands. They must be

kept going, as it required but a short stop for the treacherous sands to

engulf team and wagon alike. Men wading on either side of the string of

oxen kept them moving, and soon all were safely on the north side of the

Platte river.

Crossing the Platte, woodcut, Albert Bierstadt, 1859

Near Bessemer Bend, the Martin Handcart Company was snowbound for 10 days and 56

perished. In October 1856 the Company forded the river, wading across, dodging ice floes and was caught by a

sleet and snow storm.

Hayden Expedition camping near Bessimer Bend, 1870, photo by William Henry Jackson.

One of the survivors from the Martin Handcard Company, Elizabeth Horrocks Jackson, described the death of

her husband:

"Some of the men carried some of the women on their back or in their arms,

but others of the women tied up their skirts and waded through,

like the heroines that they were, and as they had gone through

many other rivers and creeks. My husband (Aaron Jackson) attempted

to ford the stream. He had only gone a short distance when he reached

a sandbar in the river, on which he sank down through weakness

and exhaustion. My sister, Mary Horrocks Leavitt, waded through

the water to his assistance. She raised him up to his feet. Shortly

afterward, a man came along on horseback and conveyed him to the

other side. My sister then helped me to pull my cart with my three

children and other matters on it. We had scarcely crossed the river

when we were visited with a tremendous storm of snow, hail, sand, and

fierce winds. . . .

"About nine o'clock I retired. Bedding had become very scarce so I did

not disrobe. I slept until, as it appeared to me, about midnight. I

was extremely cold. The weather was bitter. I listened to hear if my

husband breathed, he lay so still. I could not hear him. I became alarmed.

I put my hand on his body, when to my horror I discovered that my worst

fears were confirmed. My husband was dead. I called for help to the other

inmates of the tent. They could render me no aid; and there was no

alternative but to remain alone by the side of the corpse till morning.

Oh, how the dreary hours drew their tedious length along. When daylight

came, some of the male part of the company prepared the body for burial.

And oh, such a burial and funeral service. They did not remove his

clothing—he had but little. They wrapped him in a blanket and placed

him in a pile with thirteen others who had died, and then covered him

up with snow. The ground was frozen so hard that they could not dig a

grave. He was left there to sleep in peace until the trumpet of God shall

sound, and the dead in Christ shall awake and come forth in the morning

of the first resurrection. We shall then again unite our hearts

and lives, and eternity will furnish us with life forever more."

(Elizabeth Jackson, as quoted in LeRoy and Ann Hafen, Handcarts to Zion

[Glendale, Ca.: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1960], 110-13.)

And ahead of the Martin Handcart Company at Rock Creek Hollow near present day Atlantic

City, the Willie Handcart Company made camp after an enduring an 18-hour forced march. Sixty-seven

parished, among them 9 year-old Bodil Mortensen from Denmark. Bodil was sent out to gather sagebrush for

fuel. She was found frozen next to the wheel of the cart, her hand still

grasping some of the sagebrush.

Laramie Peak.

Across Nebraska there were few landmarks to indicate progress until the pioneers

came opposite Courthouse Rock, Chimney Rock, and Scotts Bluff. There on the horizon on a good

day they could see the looming presence of Laramie Peak to indicate that they were entering into

what was then known as the Black Hills. Entering what was to become Wyoming, the wagons

passed Register Cliff near the ruts depicted at the top of the page.

There, the travelers would leave their names to mark their passage.

Register Cliff as seen from the north side of

the Platte River. Photo by Geoff Dobson.

The cliff, in the center of the photo, is approximately two miles away. Between it and the viewer is the North Platte River.

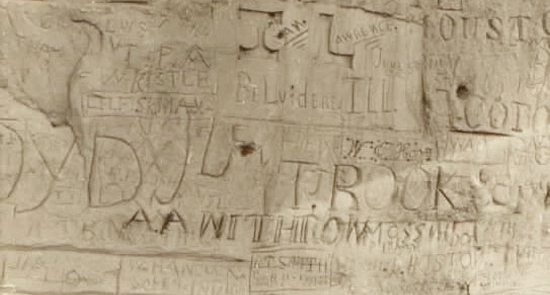

Names on Register Cliff.

The A. A. Withrow whose name appears in the photo is believed to be

Abel "Abe" Alderson Withrow (1832-1911), a saddler from Indiana who

moved to California. During the Civil War, he was a part of the "Fighting

Californians" assigned to the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry.

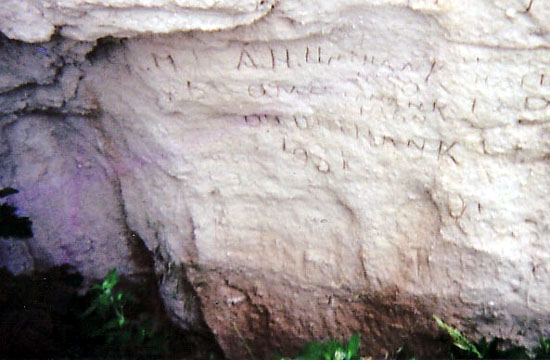

Unthank names on Register Cliff. Photo by Geoff Dobson.

In 1850, a party of Quakers from Wayne County, Indiana, passed by Register Cliff. On June 23, 1850, a

member of that party, 19-year old Alvah Hunt Unthank, inscribed his name on the cliff. See photo

above. [Writer's note: Alvah in some accounts

is also spelled "Alva"] Below Alvah's name appear the names of his cousin,

O. N. Unthank, 1869 [Oliver Nixon Unthank], and O. N.'s son, O. B. Unthank,

1931 [Oliver Brandon Unthank]. O. N. was the telegraph operator at nearby

Fort Larmamie from 1869 to 1871.

A week following the inscription of

the cliff by Alvah, near Deer Creek, present day Glenrock, another member of the party, Pusey Graves (1813-1899), noted in his

diary:

Lay by today to doctor and nurse Alvah. June 30 Alvah getting worse it's quite hopeless

complaining none. July 1 Alvah is rapidly sinking. July 2 in the early

morning hours Alvah died.

And before Alvah died without murmur or complaint, he bade his father, Jonathan, also a

member of the company, to be of "good cheer."

|

Writer's notes: Some question exists as to the relationship of Alvah to Oliver. One source

alleges that Oliver was Alvah's nephew. Alvah and Oliver Nixon Unthank were cousins. Oliver's

father was John Allen Unthank (1819-1902). John Allen Unthank's father was

John Unthank, born 1780, who had three sons in addition to John Allen:

Jonathan born 1807, Joseph born 1815, and William M born 1824. Alvah's parents were

Jonathan and Susan Williams Unthank. Alvah's father was a merchant and Quaker minister in New

Garden Township, Indiana, and was active in the abolitionist movement. At the time,

Wayne County was regarded as a "hot-bed of abolitionism" and provided

a number of Underground Railway stations on the route to Windsor in British

territory. Susan

remarried to David Willcuts in 1865, but by the time of the 1880 census was residing with another

son, Alfred W. Unthank, who named one of his sons Alvah. Like other

forty-niners, both Pusey Graves and Solomon Woody returned home to Wayne County after having "seen the

elephant" in California.

|

Near a curve in the Platte, today overlooked by a power plant in the distance,

Alvah was buried in a grave marked with a slab of sandstone with the simple inscription,

A. H. Unthank

Wayne Co. Ind.

Died July 2, 1850

Grave of Alvah Unthank

The slab was inscribed by another member

of the company, Solomon Woody. Marked graves were unusual along the trail. In most

instances, those dying were buried in the roadway in order to prevent the

scavengers such as prairie wolves picking up the scent of the dead. In 1852, a Col.

Blodgett noted of the Emigrants Road, "From the imperfect manner in which

the dead are buried, the wolves soon scent and drag them from their shallow graves,

strewing the trail with human bones."

In the area are the graves of two others who did not

complete the trek to California or Oregon. Two miles to the west of Glenrock lie the graves of J. P. Parker and

Martin Ringo. Of J. P. Parker not much is known. He was born, he died, and his mortal remains lie

in a marked grave along side the Oregon Trail, now old U.S. 20. Of Martin Ringo (1819-1864) more is known because of his

son, John Peters "Johnny" Ringo (1850-1882).

In 1864, Martin Ringo left Missouri with his wife, Mary Peters Ringo, and five children: John, Albert, Fanny, Enna and Mattie.

Some authorities indicate

that the reason for departure was the violence of the Civil War in Missouri, others claim the trip was due to

health. Martin Ringo suffered from tuberculosis and, thus, sought the healthful clime of

California where Mary Ringo had relatives. On the journey, the party had sucessfully parried off an

Indian attack, but near Deer Creek a freak accident took the life of Martin Ringo in a most grusome manner, his shotgun

discharged with the full blast entering Ringo's face and out the top of his head. His 14 year-old son was thus

required to take on the role of the man of the family and the wagons continued on to

California.

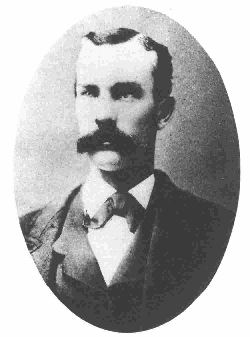

Johnny Ringo

Motion pictures and television have misportrayed the great mystery of Johnny Ringo. The issue is not whether he was

a great outlaw, terrifying to all, or a misunderstood dreamer, college educated and reciting Shakespeare. He was neither.

Ringo ultimately drifted to Texas and participated in the Mason County War. In the war, he was charged with

murder but was acquitted. In Texas, he was also charged with Disturbing the

Peace for which he was fined $75.00 From there he drifted

to New Mexico and to Tombstone, Arizona Territory. Later, in Arizona,

Ringo shot up a saloon. Quite simply, Ringo had a problem with alcohol. In

Arizona he went to work for the Clantons, at a time when an unpleasantness in Cochise County arose between

cowboys such as the Clantons, and miners represented by the Earp Brothers and

Doc Holliday. The unpleasantness resulted in persons unknown attempting to

kill Virgil Earp. Virgil was left lame for life. Then ensued the "Shootout at the

O.K Corral" (at the time Ringo was in California). The unpleasantness culminated in the murder of Morgan Earp by persons unknown.

Upon his return to Tombstone, Ringo challenged Wyatt Earp to a duel in Allen Street. Nothing,

however, came of the challenge.

About the beginning of July, 1882, Ringo started on a binge. On July 9, he was seen in Galeyville, still drinking

heavily. By July 11 he had left town. On July 14, a teamster, John Yoast, discovered Ringo's body leaning

against a tree, a .45 Colt in his in his right hand with five cartridges in the chambers, a bullet hole

in his right temple, and one of his cartridge belts on upside down. There was

an apparent knife cut on his forehead and scalp. He was dressed in hat, shirt, vest, pants, drawers,

and socks, but no boots. According to some, there were wrapped around his feets strips of

cloth from his undershirt. It has been contended that this was to protect his feet as

if Ringo was walking barefoot on the rocks. Other sources claim that the cloth was clean and

dry so that Ringo could not have walked with the cloth. Yet others claim that Ringo's feet and hands were bound by

strips of cloth ripped from his coat and that his right hand was held in

position by his watch chain. Two weeks later, Ringo's horse was found, still saddled and Ringo's

boots strapped to the saddle. The coroner's jury verdict was suicide.

Suspicion of murder has fallen on Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday who

may have believed that Ringo was involved in the murder of Morgan. Some sources claim that

Wyatt later admitted to Ringo's murder. This is denied by others. They claim the "admission" was only to

circumstantial evidence. Those contending for suicide, note that

Doc Holliday could not have been involved. He had an ironclad alibi. He was entering a plea

to an indictment for larceny in Pueblo at the time. Others upon whom suspicion fell included

"Buckskin" Frank Leslie and Johnnie "Behind the Deuce" O'Rourk. Today, only one thing is

certain -- Johnny Ringo did not die with his boots on.

A Soldier's Grave near Three Crossings Station, 1870. Photo by William Henry Jackson.

The grave is that of Pvt. Bennett Tribbett, Company B., 1st Battalion, 6th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry who died of

appendicitis on December 14, 1862.One of his fellow soldiers,

Pvt. Anthony Barleon wrote Bennett’s sister, Arviley:

We made a coffin of such lumber that we had which of course were rough boards but we planed

them off as smooth as we could. We dressed him up in his best clothes which were new and clean,

laid a blanket around him, and we tucked a blanket around the coffin which made it look a

little better… When the time arrived for his burial he was bore off by the arms of 6 of his

former associates accompanied by an escort of six men who performed the usual military escort

and ceremony. When we arrived at the grave we put the coffin in and the escort fired three

rounds over his grave. So he was buried with all the military honors of a soldier.

The 6th Ohio was later merged with the 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry. It was mustered out on July 14, 1866. The grave marker is now in the

Fort Caspar Museum. The site of Three Crossings Station is now on private property.

Music this Page:

The Leaving of Liverpool

Harmonica and Guitar

Courtesy of Horse Creek Cowboy

Now I'm leaving Liverpool, bound out for 'Frisco Bay

I'm leaving my sweetheart behind me,

but I'll come back and marry you someday.

Oh, when I'm far away at sea, I'll always think of you

And today I'm leaving Liverpool and the landing stage for sea.

Chorus:

Singing fare you well, my own true love.

When I return, united we will be.

For it ain't the leaving of Liverpool that grieves me,

But, me darling, when I thinks of you.

Now I know I'll be a long time away on this voyage to 'Frisco Bay,

We're off to California, where there's lots of gold today,

I'll bring you back silk dresses, and lots of finery.

I'll bring you presents of all sorts,

and my money I'll get from the sea.

Repeat Chorus

Well, I wrote a note and dropped it on the landing stage for her,

Telling her that I would pray for her, God knows, when I was at sea.

I'll go about my duties, always thinking about you

And when I do return, I'll marry you, my Sue.

Repeat Chorus

Writer's notes: The song is popular in Ireland as many of the Irish coming to America came through

Liverpool. Additionally, a large portion of the European and Scandinavian emigrants to the United States,

embarked from Liverpool. From Europe, the emigrants crossed the North Sea to Hull or

other ports on the eastern side of the United Kingdom. There, they then were transported to Liverpool on emigrant trains. The trains

generally consisted of only third class carriages the compartments of which were fitted with wooden

seating. The emigrants then proceeded to the landing stage for the

Princes and George Docks for boarding their respective ships. The landing stage was about three-fourths of a mile long.

Today, the Albert Dock is one of the leading tourist attractions in Northwest England. It has

museums devoted to the Beatles, the slave trade, and maritime history as well as hotels, and trendy restaurants.

One may tour the harbour in a "Yellow Duckmarine." There are two

versions of the song, the one above dates from about the time of the California Gold Rush and a later one

sung by seamen dating between 1860 and 1874 is featured on the page devoted to civilian ships named

Wyoming. For more on The Leaving of Liverpool see

American Folklife Center News, summer-Fall, 2008.

Next page: Oregon Trail continued.

|