|

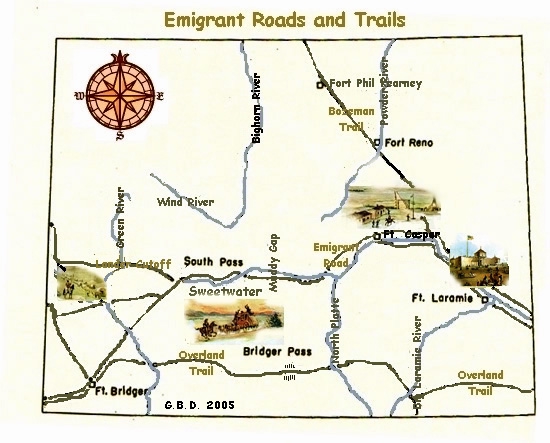

Map of the Emigrants Road

As the great trapping era in what was to become Wyoming ended, a wave of emigration to the fertile valleys

of Oregon began. In 1845, Joseph and Hyrum Smith, founders of the Mormon Church, were arrested for

inciting a riot. On June 27 of that year, a mob with faces blackened broke into the

jail in which the two were confined and Joseph Smith and Hyrum were shot dead. Brigham Young, one of the twelve apostles

designated as the sucessors to Smith, emerged with a revelation:

And from this place ye shall go forth into the regions westward; and inasmuch

as ye shall find them that will receive you, ye shall build up my Church in every

region, until the time shall come when it shall be revealed unto you from on high,

where the city of the New Jerusalem shall be prepared, that ye may be gathered in * * * *

And on the morning of January 24, 1848, James Marshall was at work on a millrace

on the South Fork of the American River. There in the gravel, a nugget of a shiny

metal which proved to be gold was discovered. Thus, conditions combined for the perfect

storm of emigration: farmers settling in Oregon, Mormons marching to Zion, and 49'ers seeking fortunes

in the gold fields of California. Each advanced on separate trails all of which combined in eastern Wyoming and all of which

separated in western Wyoming.

Emigrants Crossing the Plains, Albert Bierstatd.

The Emigrant Road over which the early pioneers of California, Oregon, and Utah traveled was not a single

road but a number of paths. These included the Oregon Trail, the Mormon Trail, the California Trail,

and the Sublette Cutoff, as well as the Lander Cutoff previously discussed, and the Cherokee Trail discussed with regard to

Saratoga. The latter trail, itself, consisted of the

Northern and Southern routes. Professor T. E. Larson in his History of Wyoming takes the

position that as to the ultimate history of Wyoming, the trails are without

significance:

The travelers spent less than thirty days in Wyoming and left little besides ruts, names and dates on

trailside cliffs, a few place names, and some graves. Indeed, exfoliation removed

the early names from Independence Rock a long time ago. Like the

mountain men, the emigrants left no significant imprint on modern

Wyoming. Larson, 2nd Edition Revised, p. 10.

The present writer respectfully demurs. While it is popularly regarded that the trails fell into disuse and today

consist of a few ruts and ruined stage stations, the trails were continually relocated and upgraded. In truth,

the Lincoln Highway, U.S. 30, and I-80 are all the successors of the original

Emigrant Road. I-80 essentially follows the same route as the Overland Trail, the Cherokee Trail and the California

Trail and serves the same purposes. The Interstate System is a part of a Defense Highway System, inspired in part by Lt. Col.

Eisenhower's military convoy along the same route in 1919. Eisenhower's Packard trucks served the same purpose as the Murphy wagons of Albert Sidney

Johnston in 1857, the Schuttler wagons of the Mormons, the military Studebakers following the Civil War,

and the giant Freightliners and Macks of today. The Concord coaches of Ben Holladay were

the Greyhound coaches of today. Those highways today should be taken as a monument to the perseverance of the

pioneers, freighters, soldiers and pony express riders who traveled along the Emigrant Roads.

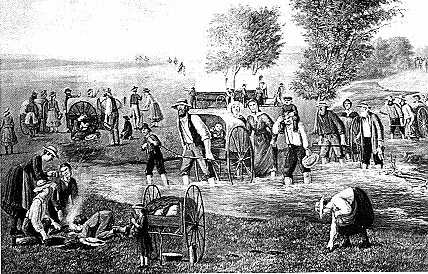

Emigrant Camp. Woodcut, A. R. Waud, Harper's Weekly, 1871.

It has been estimated that during the 12 year period of 1849 through 1860, some

275,000 persons traveled through Wyoming on the trails. Thus, Wyoming has been described as a place through which

one passed on the way to someplace else. The beginning of the journey was typically either Westport, Missouri, or

Council Bluffs, Iowa. The journey to California or Oregon would typically take six months and would have to

start early in order to miss the early snows of the Sierra Nevada. It has been estimated that some 20,000 emigrants to

California died on the trail. In the

popular mind the dangers of the trail might consist of wild Indians attacking the train. In reality, the dangers

were more of disease, accident, weather, and boredom. While Indians might appropriate stray stock, few if any

of the pioneers fell to Indian arrows. The pioneers were much better armed. Few

trains were out of sight of another. Thus, the trains were not attacked. The trains were

circled at night, but the purpose was to form a corral for the stock. The wagons would be arranged

with the right front wheel of one wagon against the left hind wheel of another,

the wagons angled inward, throwing the tongues inside of the circle. The tongues were then propped up with the yokes of

the teams.

In the woodcut above, one train is already camped for the night, as another joins it. As noted, boredom was a problem.

One early pioneer expressed the thought that, after having spent 30 days crossing Nebraska with

hardly a change of scenery, he hoped the Indians would attack to relieve the boredom. A wagon train on a

good day might make 25 miles, but typically 15. Thus, at Muddy Gap, west of Devils Gate, for two days the emigrants could

see the gap through which they had just passed.

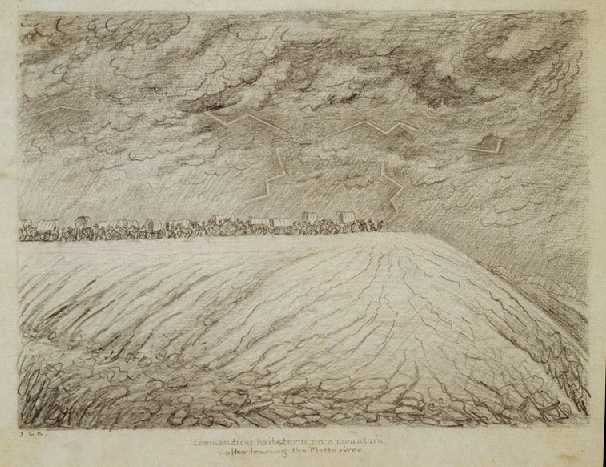

Emigrants Crossing the Plains. Hand Colored steel

engraving by Henry Bryan Hall after a drawing by Felix Octavius Carr Darley. Published by

D. Appleton & Company, 1869.

Death by disease was taken as a matter of fact. L. H. Wooley, a 49'er, in his California 1849-1913, recounted

his trip across the plains in 1849. He noted of the journey across

Nebraska:

In the morning we started on our journey to travel over a level

untimbered, uninhabited country for nearly four hundred miles, without

anything of especial interest occurring save cholera, from which there

was terrible suffering. We lost about seventy-five of our number before

we reached Fort Laramie, seven hundred miles from Missouri.

A typical accident was being run over by the iron tired wagon wheels.

Children would be orphaned by death of their parents.

Catherine Sager Pringle, as a small girl traveling with her parents and siblings to

Oregon, had her leg crushed beneath the wheels of the wagon. Later she

wrote in Across the Plains in 1844 of how she and her six siblings were orphaned:

After [Fort] Laramie we entered the great American desert, which was hard on

the teams. Sickness became common. Father and the boys were all sick, and we

were dependent for a driver on the Dutch doctor who set my leg. He offered

his services and was employed, but though an excellent surgeon, he knew

little about driving oxen. Some of them often had to rise from their sick

beds to wade streams and get the oxen safely across. One day four buffalo

ran between our wagon and the one behind. Though feeble, father seized his

gun and gave chase to them. This imprudent act prostrated him again, and it

soon became apparent that his days were numbered. He was fully conscious of

the fact, but could not be reconciled to the thought of leaving his large

and helpless family in such precarious circumstances. The evening before his

death we crossed Green River and camped on the bank. Looking where I lay

helpless, he said: "Poor child! What will become of you?" Captain Shaw

found him weeping bitterly. He said his last hour had come, and his heart

was filled with anguish for his family. His wife was ill, the children

small, and one likely to be a cripple. They had no relatives near, and a

long journey lay before them. In piteous tones he begged the Captain to

take charge of them and see them through. This he stoutly promised.

Father was buried the next day on the banks of Green River. His coffin

was made of two troughs dug out of the body of a tree, but next year

emigrants found his bleaching bones, as the Indians had disinterred the

remains.

* * * *

Mother planned to get to Whitman's and winter there, but she was rapidly

failing under her sorrows. The nights and mornings were very cold, and

she took cold from the exposure unavoidably. With camp fever and a sore

mouth, she fought bravely against fate for the sake of her children, but

she was taken delirious soon after reaching Fort Bridger, and was bed-fast. Travelling in this condition over a road clouded with dust, she suffered intensely. She talked of her husband, addressing him as though present, beseeching him in piteous tones to relieve her sufferings, until at last she became unconscious. Her babe was cared for by the women of the train. Those kind-hearted women would also come in at night and wash the dust from the mother's face and otherwise make her comfortable. We travelled a rough road the day she died, and she moaned fearfully all the time. At night one of the women came in as usual, but she made no reply to questions, so she thought her asleep, and washed her face, then took her hand and discovered the pulse was nearly gone. She lived but a few moments, and her last words were,"Oh, Henry! If you only knew how we have suffered." The tent was set up, the corpse laid out, and next morning we took the last look at our mother's face. The grave was near the road; willow brush was laid in the bottom and covered the body, the earth filled in -- then the

train moved on.

Her name was cut on a headboard, and that was all that could be done.

So in twenty-six days we became orphans. Seven children of us, the oldest

fourteen and the youngest a babe.

It was not callousness for the train to move on without hardly a pause. Theodore Edgar Potter in his

Autobiography, who made the

trek in 1852, described coming across a young girl from a family of seven. Her parents and four siblings had

died from smallpox. Potter's train paused four hours to bury the dead, make arrangements with a missionary for the

sale of the family's outfit and with the proceeds send the

orphan back to Virginia:

When they were taken sick three days before, their traveling associates had gone on, leaving then to take

care of themselves. It was an uncommon things for a train to lay over on account of

sickness even for one day, as it was well understood by all, before starting,

that even with the smallest amount of detention, it would take the entire season to

get through to California. The Nevada Mountains, sixteen hundred miles west of us, must be

crossed as early as October to avoid the deep snows.

Ferrying wagons across the Platte near Deer Creek, drawing by J. Goldsborough Bruff, 1849

Another danger was crossing the Platte. Various crossings were available.

Fording the river was perilous. Potter noted:

Platte River is a dangerous river to cross, as its bed is composed of quicksand which is

continually changing. during one week the channel may be on the south side and

the next week on the north. Many wagons were lost by emigrants crossing that this

ford. The breaking of a kingbolt, wheel or anything that could not be quickly repaired

gave the rapid current its change to wash the loose sand from under the wheels and in an

hour's time the wagon would have settled so rapidly that you could see nothing but the

white cover above the surface of the water. If the wagon was ever recovered it would be at some time

in the future when the water was running in some other part of the river bed.

Louis Guinard's Bridge at Platte River Bridge Station. Drawing by Carl F. Moellman, Co. G, 11th

Ohio Cavalry (Volunteers), 1863.

In Wyoming,

there were two privately owned bridges available, Reshaw's bridge constructed by

John Baptiste Richard about six miles south of Fort Caspar which replaced an earlier

bridge near Deer Creek (present day Glenrock), and Louis Guinard's

Bridge at was later to become Fort Caspar. Guinard's bridge was constructed in 1859. Ferrys were also available, including the Mormon Ferry near present day

Casper and a ferry at Deer Creek. All charged, however, very heavy tolls.

For much of the distance, the Oregon Trail and the Mormon Trail paralleled the Platte River. Not only did the river valley

provide a relatively flat route across Nebraska, but more importantly water. John Wyeth in his 1833 account, Oregon; A short History of a long Journey noted that

the journey along the Platte was twenty seven days, "which river we could not leave on account of the scarcity of water in the dry and

comfortless plains," but, he noted, the water was "warm and muddy; and the use of it occassioned a dirarrhea in several of our company. Dr. Jacob Wyeth, a

brother of the Captain, suffered not a little from this cause." When the company reached the Black Hills, now known as

the Laramie Mountains, "Our sick suffered extemely in ascending these hills, some of them slipped off the horses and

mules they rode on, from sheer weakness, brought on by the bowel complaint, already mentioned * * *."

"Tremendous hail storn over mountain

after leaving the Platte river," pencil by J. Goldsborough Bruff, 1849

Joseph Goldsborough Bruff (1804-1889), a government cartographer, attended West Point but resigned in lieu

of expulsion.

Discipline under some of the Superintendents such as Colonel Sylvanus Thayer and later Colonel R. E. Lee could be quite

strict. Two hundred demerits would result in automatic expulsion. Demerits were given for

such offenses as laughing, unnecessary noise, and disorderly rooms. One of the more serious

offenses, which by itself could give rise to expulsion, would be visiting a

tavern owned by Benjamin Havens (1785?-1877) in nearby Highland Falls. In one instance, only a personal

audience with the President of the United States by members of the Corps was able to

save a fellow cadet from expulsion. Following graduation, the officer saved from

expulsion was killed in the Mexican War. Another cadet narrowly escaping expulsion for

the same offense was John Hood, the last Confederate general to surrender. It has been speculated that

Bruff's resignation may have been prompted by such a visit.

Today, Bruff is noted for his detailed maps of Florida and of Mexico dating from the Mexican War. In 1849, he

was elected as captain of the Washington City and California Mining and Wagon Company which

set forth to California as a part of the 1849 gold rush. Along the way, he made detailed notes and

drew sketches. As were many of the Forty-Niners, Bruff was less than sucessful and returned east and

was employed in the Treasury Department as a draftsman. Bruff's diary reflects that it took

twenty days for the wagon train to go from Ft. Laramie to South Pass. Bruff noted that prior

emigrants lightened their loads as they went along. Thus, he noted in one

diary entry for July 22, 1849:

"In this extensive bottom are

the vestiges of camps - clothes, boots, shoes, hats, lead, iron, tin-ware,

trunks, meat, wheels, axles, wagon beds, mining tools, etc. A few hundred

yards from my camp I saw an object, which reaching proved to be a very

handsome and new Gothic bookcase! It was soon dismembered to boil our coffee

kettles."

But, on the other hand, the Gothic bookcase was far superior to the fuel the

Company had been using. Earlier, Bruff noted in his diary:

"It is the duty of the cooks on arriving at a camping place to collect chips

for cooking. It would amuse friends back home to see them make a grand rush

for the largest and driest chips. The chips burn well when dry, but if damp

or wet are smoky and almost fireproof."

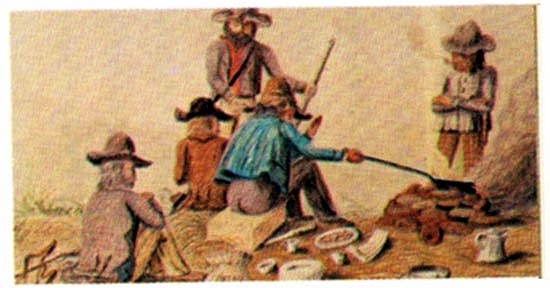

Cooking Over Buffalo Chips. Drawing by J. Goldsborough Bruff, 1849.

Others noted the lack of wood. A writer for Atlantic Montly, March 1859, commented:

At the distance of about two hundred miles

from the Missouri frontier the soil becomes so pervaded by sand, that

only scientific agriculture can render it available. Along the Platte

there is no fuel. Not a tree is visible, except the thin fringe of

cottonwoods on the margin of the river, all of which upon the south

bank, where the road runs, were hewed down and burned at every

convenient camp, during the great California emigration. When the Rocky

Mountains are entered, the only vegetation found is bunch-grass, so

called because it grows in tufts,--and the _artemisia_, or wild sage, an

odorous shrub, which sometimes attains the magnitude of a tree, with a

fibrous trunk as thick as a man's thigh, but is ordinarily a bush

about two feet in height. The bunch-grass, grown at such an elevation,

possesses extraordinary nutritive properties, even in midwinter. About

the middle of January a new growth is developed underneath the snow,

forcing off the old dry blade that ripened and shed its seed the

previous summer. From Fort Kearney to Fort Laramie, almost the only

fuel to be obtained is the dung of buffalo and oxen, called, in the

vocabulary of the region, "chips,"--the _argal_ of the Tartar deserts.

Among the mountains the sage is the chief material of the traveller's

fire. It burns with a lively, ruddy flame, and gives out an intense

heat. In the settlements of Utah all the wood consumed is hauled from

the canons, which are usually lined with pines, firs, and cedars, while

the broadsides of the mountains are nothing but terraces of volcanic

rock. The price of wood in Salt Lake City is from twelve to twenty

dollars a cord.

The last wood available to the pioneers crossing Kansas and Nebraska was near the crossing of the

Big Blue. Joel Palmer in his Journal of his Travels over the Rocky Mountains noted

the area of the Big Blue was the "last opportunity to procure timber for axle trees, wagon tongues, &c." until one

reached the Black Hills in present-day Wyoming. Besides broken axletrees and tongues on the wagons, the

iron tyred wooden wagon wheels would loosen. If the tyres actually broke, it would require blacksmithy

equipment to make repairs. Captain Wyeth attempted to cross one stream on a raft which upset causing him

to lose his anvil and vise, making repair to wheels almost impossible. If the tyres were only

loose, they could be tightened with wooden shims. Making the repairs to the wagons, slowed down

progress.

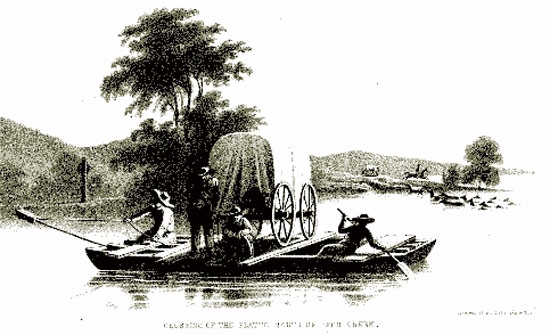

Crossing the Platte, Standbury Expedition.

Stanbury in the report of his expedition described the ferry:

Wednesday, July25. * * * * Just above the mouth of this stream

[Deer Creek], there was a ferry over the North Fork of the Platte, at which I determined to

cross the train. The means employed for this purpose were of the rudest and simplest kind. The ferry-boat was constructed of seven canoes, dug out from

cotton-wood logs, fastened side by side with poles, a couple of hewn logs

being secured across their tops, upon which the wheels of the wagons rested.

This rude raft was drawn back and forth by means of a rope stretched across the river, and secured at the ends of either bank.

Frail and insuecure as was the appearance of this very primitive ferry-boat, yet all the wagons were passed over in the course of

two hours, without the slightest accident, although many of them were very

heavily laden. The animals were driven into the stream and obliged to ferry

themselves over, which they did without loss, althoughthe river was now somewhat swollen by late rains and

the current extremely rapid and turbid. The ferrymen informed me that an

emigrant had been drowned here, the day before, in essaying to

swim his horse across, which he persisted in attempting, notwithstanding the earnest

entreaties and warnings of his friends. They told us that this man made the twenty-eighth victim drowned

in crossing the Platte this year; but I am inclined to believe that this must

be an exaggeration. The charge for ferriage was two dollars for each wagon.

The price, considering that the ferrymen had been for months encamped here, in a

little tent, exposed to the assualts of hordes of wandering savages, for the sole purpose of

affording this accommodation to travellers, was by no means extravagant.

On shallower streams or to avoid the expense, wagons could be forded across. In some instances, this

required using timber to lift the wagon boxes higher over the chassis. The extra elevation kept the goods dry.

Both Fremont in his description of his 1841 expedition and Father DeSmet who returned

from Oregon in 1846 commented as to the abandonment of goods. Father DeSmet later

wrote:

The scene we witnessed on this road presented indeed a melancholy proof of

the uncertainty which attends out highest prospects in life. The bleached

bones of animals everywhere strewed along the track, the hastily erected

mound, beneath which lie the remains of some departed friend or relative,

with an occasional tribute to his memory roughly inscribed on a board or

headstone, and hundreds of graves left without this affectionate token of

remembrance, furnished abundant evidence of the unsparing hand with which

death has thinned their ranks. The numerous shattered fragments of the

vehicles, provision, tools, etc., intended to be taken across these wild

plains, tell us another tale of reckless boldness with which many entered

up this hazardous enterprise. It is rashness to undertake this long trip

except with good animals, with very strong vehicles and with a good supply

of light provisions, such as tea, coffee, sugar, rice, dried apples,

peaches, flour and peas or beans.

For a four-year period, 1856-1860, some 3,500 Mormons used handcarts to move westward.

The carts each weighed about 60 lbs. They had the advantage of not only being

less expensive, but actually cut about three weeks off the trek from Iowa City to

Utah.

Handcarts, drawing by Carl C. A. Christensen

Carl Cristian Anton Christensen (1831-1912), a native of Denmark, studied at the

Royal Acadamy of Art in Copenhagen and converted to Mormonism in 1850. In 1857, he came to

the United States on the Perpetual Emigrating Fund ship and was one of those who pulled

a handcard from Iowa to Utah. Christensen is noted for his documentation through art of the

early years of the Mormon Church. In 1878, he commenced the painting of 22 paintings which

where subsequently sewn together to form a scroll known as the "Mormon Panorama."

And those that came across Emigrants' Trail, whether from the "States" or from a foreign land, knew

that there was little likelihood that they would ever see their friends, relatives, or native

soil again.

Music this page, courtesy Horse Creek Cowboy:

Scottish Emigrant's Farewell

Farewell, farewell, my native home,

Thy lonely glens and heath-clad mountains;

Farewell, thy fields o' storied fame,

Thy leafy shaws And sparklin' fountains;

Nae mair I'll climb the Pentland's steep,

Nor wander by the Esk's clear river;

I seek a home far o'er the deep,

My native land, farewell forever.

Thou land wi' love and freedom crowned

La ilk wee cot, an' lordly dwellin'

Many manly-hearted youths be found,

And maids in ev'ry grace excelliin';

The land where Bruce and Wallace wight

For freedom fought in days o' danger,

Ne'er crouch'd to proud usurper's might,

But foremost stood, wrong's stern avenger,

Though far frae thee, my native shore,

An' toss'd on life's tempestuous ocean,

My heart, aye, Scottish to the core,

Shall cling to thee wi' warm devotion;

An' while the wavin' heather grows,

And onward rows the windin' river.

The toast be, Scotland's broomy knowes,

Her mountains, rocks and glens forever.

To download this and other free midi and MP3 music,

see

Horse Creek Cowboy Band.

|

Next page: Oregon Trail continued.

|