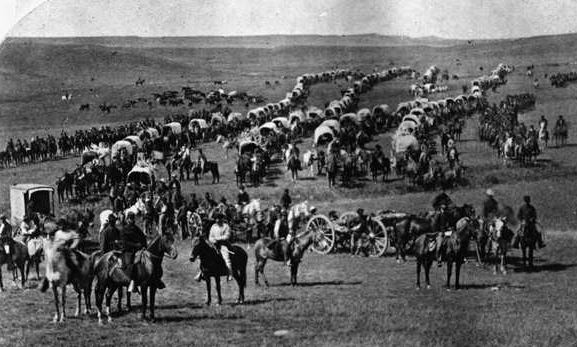

Custer Expedition into Black Hills, 1874, photo by

William H. Illingworth. Custer in light colored clothing to left of center.

Under the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie the Black Hills, among other places, were set aside

"for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation of the Indians herein

named, and for such other friendly tribes or individual Indians as from

time to time they may be willing, with the consent of the United States,

to admit amongst them; and the United States now solemnly agrees that no

persons except those herein designated and authorized so to do, and except

such officers, agents, and employes of the Government as may be authorized

to enter upon Indian reservations in discharge of duties enjoined by law,

shall ever be permitted to pass over, settle upon, or reside in the

territory described in this article."

The Custer Expedition of 1874 was a direct violation of the Ft. Laramie Treaty of 1868. Custer made the most

of the expedition which consisted of a company of approximately 1,000, including a

16-piece regimental band mounted on white horses, 110 Studebaker wagons, scientists, newspaper

correspondents, official photographer William H. Illingworth (1842-1893) of St. Paul, and President Grant's son, Fred Dent Grant. On the expedition

gold was discovered near what later was Custer City.

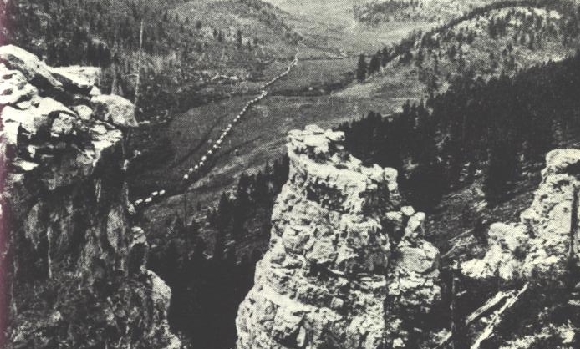

Custer Expedition of 1874 in the Black Hills, photo by

William H. Illingworth.

The discovery of gold led a far worse violation of the treaty,

a gold rush into the Black Hills and the settlement of cities such as

Deadwood. With the discovery of the gold, Custer dispatched scout Charles Alexander "Lonesome Charley" Reynolds

(1842-1876) to Fort Laramie to relay the word by telegraph to Gen. Terry in St. Paul.

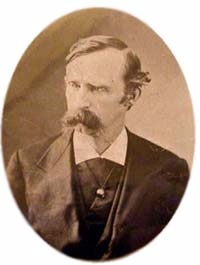

Charles A. Reynolds

Reynolds had served in the 4th Kansas Volunteer Infantry and the 10th Kansas Infantry during the

Civil War. Because of his taciturn nature, Renolds earned the nickname of "Lonesome

Charley." The five-foot six-inch scout had served in Gen. Stanley's expeditions to the

Yellowstone in 1872 and 1873. Reynolds later was to serve in Ludlow's 1875 expedition and was to

die at Little Bighorn. Reynold's trek to Ft. Laramie was itself memorable. Mrs.

Custer in her Boots and Saddles described the trip:

He had only his compass to guide him, for there was not even a trail.

The country was infested with Indians, and he could only travel at night.

During the day he hid his horse as well as he could in the underbrush, and

lay down in the long grass. In spite of these precautions he was sometimes

so exposed that be could hear the voices of Indians passing near. He often

crossed Indian trails on his journey. The last nights of his march he was

compelled to walk, as his horse was exhausted, and he found no water for

hours.

The frontiersmen frequently dig in the beds of dried-up streams and find

water, but this resource failed. His lips became so parched and his throat

so swollen that he could not close his mouth. In this condition he reached

Fort Laramie and delivered his despatches. It was from the people of that

post that the general heard of his narrow escape. He came quietly back to

his post at Fort Lincoln, and only confessed to his dangers when closely

questioned by the general long afterwards.

Members of Custer's

own expedition began staking claims. With the word out it was impossible

to keep gold-seekers out of the Black Hills. For discussion of the gold rush see Cheyenne.

Deadwood City, 1876

With the impossibility of removing the Whites, the government determined that

the Indians must be confined to smaller reservations. Enforcement of this

policy, in turn, led to the necessity of military operations against the Indians.

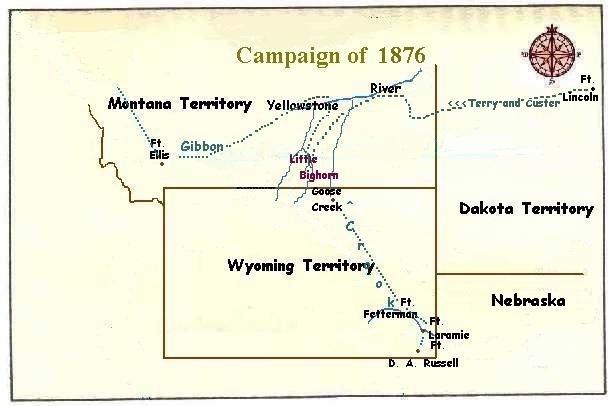

Map of Campaign of 1876.

In the fall of 1875, the order came forth from

the Bureau of Indian Affairs that the Sioux and the Cheyenne were to return to their

reservation. The order was ignored and, thus, the army was requested to enforce the order.

George Armstrong Custer, Studio Portrait by

Willian H. Illingworth, 97 East Seventh Street, St. Paul, Minn., 1874.

George Armstrong Custer, Studio Portrait by

Willian H. Illingworth, 97 East Seventh Street, St. Paul, Minn., 1874.

Generals Sherman and Sheridan devised a plan whereby Gen. George Crook would move northward from

Fort D. A. Russell to Fort Fetterman and from there northward. Units of the Seventh Cavalry would move westward from Fort Abraham Lincoln near Bismarck. Col.

John Gibbon would move southward from Fort Shaw, Montana, to Fort Ellis and from there eastward to meet

up with the Seventh Cavalry and Crook. The Indians would be encircled and forced back onto the

reservation. With great distances and difficulties of communication between the

separated units, the plan would be, in aftersight, almost impossible of implementation.

In the spring of 1876, implementation of the plan was delayed because of bad weather. It was contemplated that

the Seventh Cavalry units would proceeds westwardly under Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer. On March 7, Custer departed St. Paul,

Minnesota, via special train for Fort Abraham Lincoln. Notwithstanding the use of three

locomotives and two snow plows, the train became stuck in drifts blocking the

rails. Thus, Custer was left to cool his heels in his snow-bound private car until his

brother, Tom Custer, was able to rescue Custer and his party with a mule-drawn sleigh. On March 15, two days after his

arrival at Ft. Lincoln, Custer was summoned back to Washington to testify before

Congress in its investigation of corruption by Secretary of War William Belknap.

Alfred H. Terry

Alfred H. Terry

The railroad remained blocked by the snowdrifts. Indeed, the remaining passengers on

the train were left to their own devices until the train was able to free itself after the 21st. Thus,

Custer departed from Ft. Lincoln on the stage. With Custer in Washington, being feted by Democrats and icily ignored by

President Grant, a debate commenced as to who was to lead the Seventh Cavalry, General

Alfred H. Terry, a lawyer with no Indian experience, or Major Marcus A. Reno, who was generally disliked because

of ungentlemanly behavior. Plans had called for the Seventh Cavalry to

depart Ft. Lincoln on April 6. Yet on May 1, Custer still sat in the presidential anteroom awaiting an

audience with President Grant who, after five hours, sent out a message that the President was

too busy to see Custer. Custer departed again for Ft. Lincoln, but upon his arrival in

Chicago learned that he was again summoned back to Washington. Only a personal intercession with President Grant by Terry and

Sheridan finally permitted Custer to rejoin his units. Accordingly, on May 14, the day before the revised date

of departure from Ft. Lincoln, Mark Kellog, a stringer for the

New York Herald, wrote:

Gen. George A. Custer, dressed in a dashing suit of buckskin, is prominent everywhere.

Here, there, flitting to and fro. in his quick eager way, taking in everything

connected with his command, as well as generally, with the keen, incisive manner for

which he is so well known. The General is full of perfect readiness for a

fray with the hostile red devils, and woe to the body of scalp-lifters that

comes within reach of himself and brave companions in arms.

Next page: George Crook -- The Battle of the Rosebud.

|