|

General Crook's Headquarters, Fort Fetterman, Harper's Weekly, 1876

The above woodcut illustrates Fort Fetterman during General George Crook's winter campaign of early 1876 into the

Powder River Country. Compare with photos below. On March 1, 1876, General Crook left Ft. Fetterman with

883 men and a herd of 45 beef cattle. On March 5 the troop ran into a blizzard in which

it was so cold that thermometers did not register and the men while eating had to heat

their forks in the coals of their fires to prevent the tines from freezing to their tongues. Following the Battle of Powder River on March

17, Crook returned to Ft. Fetterman.

"Thirty Below and a Blizzard Raging," Frederic Remmington, McClure's Magazine, June 1899

George Crook (1830*-1890) graduated near the bottom of his class at West Point in 1852.

[*Writer's note: various sources give Crook's date of birth as Sept. 8, 1828, 1829, and 1830. The P.B.S.

website, The West gives his date of birth as 1828. His grave marker in

Arlington National Cemetery shows 1830.] Crook saw duty during the Civil War at

Second Manassas [Second Bull Run], Chichamauga, and in the Shenandoah Valley, including

Cedar Creek.

[Writer's personal note: My wife's great-grandparents' family farm was

on Cedar Creek Battlefield. The house was used during the battle as a hospital.

Thus, my mother-in-law had strong feelings, and when she learned that we were to be married, had a

spell of the "vapors," and told my wife, "Oh, to think of grandfather's sword --

who fought under Imboden under Stonewall Jackson -- hanging on a Yankee's mantle." Guess where that

sword is now hanging. John D. Imboden (1823-1895), a lawyer, was commissioned as

a Brigadier General in 1863 and commanded the Department of the Valley, and after the

death of Stonewall Jackson, had primary responsibility for the defense of the

Shenadoah Valley against Crook.]

Among those serving under Crook was Rutherford B. Hayes. Crook was

subsequently captured by Confederate forces and held in Richmond for a short period

before he was exchanged.

General George Crook, note wolfskin collar.

In 1871 Crook was assigned to Arizona. He was transferred to

the northern plains in 1875. In 1882, Crook was reassigned to Arizona where he engaged

in the search for Geronimo until 1886 when he was relieved of command and replaced by

Nelson A. Miles. For the remainder of his military career he fought for the

release of Apache scouts who had faithfully served under him in Arizona and were

rewarded for their efforts by bing imprisoned in Fort Marion (now Castillo de San Marcos) in

St. Augustine, Florida or in Fort Pickens, Pensacola, Florida. After being relieved of command in

Arizona, Crook served as Commander of the Department of the Platte until 1888 when he was

given command of the Department of the Missouri where he served until his death in 1890. Upon learning of Crook's death,

Red Cloud, Makhpiya-Luta (1822-1909), said: "Crook never lied to us. His words gave the people hope. He died. Their hope died again."

The same thought was echoed by Crook's aide de camp, John G. Bourke, who noted:

"If there was one point in his character which shone more resplendent

than any other, it was his absolute integrity in his dealings with

representatives of inferior races: he was not content with telling the

truth, he was careful to see that the interpretation had been so made

that the Indians understood every word and grasped every idea..."

[Writer's note: Some have observed that the reference to "inferior"

was not intended as being racist as evidencing a prejudice against Indians,

but was more paternalistic, in the sense that it

was the duty of the white man to bring civilization to others through the

reservation system and schools similar to Carlisle. Until fully civilized,

the Indians were more like children

to be educated and protected by the Great Father in Washington or the Great Mother in London.]

Former President Hayes served

as one of Gen. Crook's pallbearers.

Looking Northeast from Ft. Fetterman, 2001, Photo by Geoff Dobson

Gen. Crook's camp at Ft. Fetterman was located on the field on the far side of the Platte River toward

the center of the above photo. From here on May 29, 1876, he set forth toward the

former site of Ft. Reno with 1,000 cavalry and infantry enlisted men, 50

officers, and 262 Crow and Shoshoni scouts.

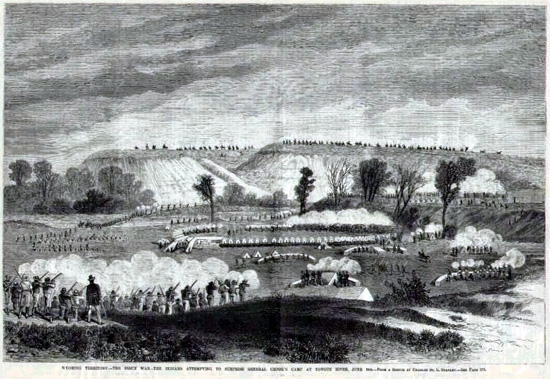

Wyoming Territory--The Sioux War --

The Indians Attempting to Surprise General Crook's Camp at Tongue River, June 9th, sketch by Charles St. G.

Stanley, Leslie's Illustrated News, 1876.

The encounter at Tongue River consisted of an attack by about 200 Northern Cheyenne under

Little Hawk. Earlier in the day, the soldiers relaxed by horse racing. The races were ended when

a bullet fired from across the river hit Capt. Andrew Burt's horse in the leg. The horse had

just won its race. The total casualties were two Indians killed or wounded, the wound to

Capt. Burt's horse, a wound to Lt. Robertson's horse, one mule killed, and

two soldiers with contusions from spent bullets.

By June 12, Crook had reached

Clear Creek near the present site of Buffalo. From there he proceeded up to the confluence of

Big and Little Goose Creeks at present day Sheridan. Because they would slow him down, Crook left his

wagons and ambulances behind at Goose Creek.

"A Government Six Mired Down," Frederic Remmington

On June 14, 176 Crow and

86 Shoshoni under Chief Washakie joined Crook's forces. A reporter for the

New York Herald, described the Shoshoni:

[N]early every Shoshone in going to war, carries a long white wand

ornamented with pennants or streamers of fur, hair and red cloth.

They wear parti-colored blankets, and ride usually either white or spotted

ponies, whose tails and manes they daub with red or orange paint.

Nothing could be more bright and picturesque than the whole body of

friendly Indians as they galloped by the long column of the expedition

early in the first morning of the march, as it wound around the base

of the low foot hills called the Chetish or Wolf Mountains, which

were traversed in moving toward the head waters of Rosebud Creek. Several

of the Snakes still carry their ancient spears and round shields of

buffalo horn and elk hide, besides their modern firearms.

Unbeknowst to Crook a large force of Northern Cheyenne and Sioux awaited at

Rosebud forewarned of Crook's approach by Little Hawk's encounter at Tongue River.

Site of the Battle of the Rosebud, L. A. Huffman, 1918

On June 17, the Company was

surprised by Indians at the Rosebud just north of the Wyoming Line, resulting in

Crook's withdrawal back to the Tongue River. At the Rosebud Crook encountered

some 1,500 Indians. Crook's casualties were nine killed and 19 wounded including one soldier

who accidently shot himself. Crook had left his wagons behind at Goose Creek.

Thus, the wounded had to be evacuated riding their own horses or be brought out on

travois. One who was brought out by travois was Capt. Guy V. Henry (1839-1899). Capt. Henry in an article

in Harper's Weekly, July 7, 1895, "Adventures of American Army and

Navy Officers; Wounded in an Indian Fight," recalled:

I felt a sharp sting as of being slapped in the face, and a blinding rush

of blook to my head and eyes. A rifle bullet had struck me in the face,

under my left eye, passing through the upper part of my mouth, under the nose, and

out below the right eye. I retained my saddle for a moment, then dismounted and

lay on the ground. The Sioux in their desperate charge actually passed over me and

had it not been for Washakie, chief of the Shoshones, fighting over my body; my

scalp would have been lifted.

Captain Henry in his article was, perhaps unduly modest.There was but scant medical attention available. Henry was blinded. For the whole day, according to

Cyrus Townsend Brady, "What They Are There For," Harper's, Vol. XXXIv, p. 409, Henry was required to lie on the

ground in the heat, with little water, and "practically left to die." His only shade was that of a restive horse.

When battle was over, the travois was made of two saplings and suspended between two mules. As Capt. Henry was being evacuated, the mules carrying the travois shied, throwing

Capt. Henry off the conveyance twenty feet down a ravine. Nevertheless, the

captain pronounced himself "bully." He realy wasn't "bully." The poles of the travois were short and several times on the two hundred miles back to Fetterman,

he was hit in the head by the head of the rear-most mule. Finally, Henry was turned about, his head forward with the risk, of course, of

being kicked to death by the forward mule. At Fetterman, the Platte had to be crossed on a cable ferry. Unfortunately,

the river was running high and as Henry was being prepared for loading on the ferry, the ropes broke and the ferry was dashed

to pieces. He was ultimately taken across in a small skiff. Finally, sufficient troops became available for an

escort to the railroad at Medicine Bow. It was the Fourth of July, celebrated by the cowboys and citizens by the firing of

six guns. Two bullets passed through Henry's tent just above his head. As the train passed over

Sherman Hill, the combination of the elevation and the chloral and other medicines almost killed him. It took over a year for

Henry to recovery sufficiently for active duty. Following the battle, Henry was brevetted as a

brigadier general. During the Spanish American War, Henry was promoted to major general.

The Battle of the Rosebud is regarded as

an Indian victory. Some contend that Crook's failure to advise of the

strength of Indian forces was one of the causes of the loss by

Custer eight days later at the Little Big Horn or Greasy Grass.

Next page: The Battle of the Little Bighorn.

|