|

Bear feeding on garbage, approx. 1911. Photo by F. Jay Haynes.

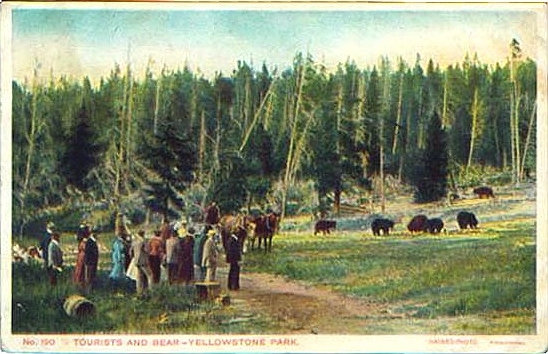

As observed on the previous page,

the problem of the mixing of bear and tourists has been of concern to the

Park from almost the beginning. Bear were commonly invading the garbage

dumps of the hotels by 1888. By 1891, the problem was noted by the

Park Superintendent. Indeed, the dumping of the hotel garbage became a

major attraction for tourists.

Bear awaiting dumping of garbage, 1909, photo by

F. Jay Haynes

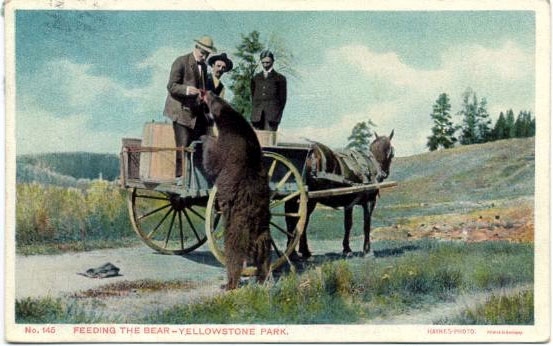

By 1910, the bear were found begging food from the

tourists.

Tourists feeding a bear, 1912, photo by

F. Jay Haynes.

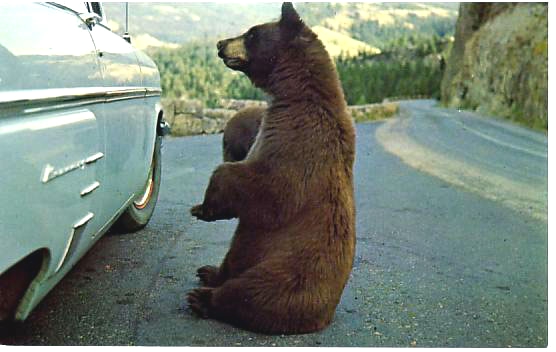

The conflict between tourists and bears steadily worsened, with an average of 48 tourists a

year being injured in conflicts between 1931 and 1959. The conflicts may have been

unintended on the part of the bear. One incident that was described by rangers as

illustrative of the problem was the lady from a tour bus who was feeding a bear. The

bear, as in the photo above, was standing upright. One of the lady's friends in the

bus asked her to look around for a photo. The lady turned. The bear, apparently thinking the

feeding was over, came down with his claws accidently grabbing the lady's dress, leaving

the lady in a state of disrobement. Needless to say, the lady was unhappy and demanded

that the bear be punished. The writer has, himself, warned one tourist against

going down into a small valley for a closer view of two cute small cubs. Mother might not

have understood.

Begging bear, approx. 1954

In 1970, regulations were adopted by the Park Service forbidding the feeding of bears.

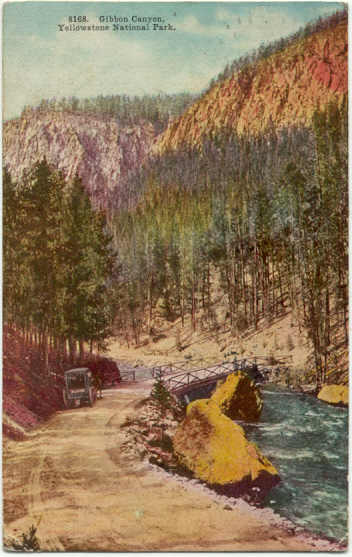

Gibbon Canyon, 1910, to left

Gibbon Canyon as well as the Gibbon Geyser Basin and Gibbon River are each named after

John Gibbon. Gibbon entered West Point at age 15 and served with distinction in the

Union Army during the Civil War. He authorized a military escort for the Washburn expedition into

Yellowstone, but is most noted for two military encounters: (1.) At the Little Big Horn Custer

disregarded orders that he was not to attack Indians until after Gibbon was in position. Gibbon

arrived following the results of Custer's failure to obey orders, relieved Majors Frederick Benteen and Marcus

Reno and discovered the remains of Custer's command; (2.) The pursuit of Chief Joseph of the Nex Perce. In 1876,

the Government determined that the Nez Perce were to be removed from the Wallowa Valley in eastern Oregon. Part of

the valley had been set aside for the Nez Perce by executive order of President Grant only three

years before. After the government gave the tribe an ultimatum, three young braves killed four whites believed

to have committed crimes against the Indians. Pursued by the one-armed General Oliver Otis Howard, the

Indians fled to the east through Lolo Pass and then southward.

On August 21, 1877, the small

band entered the Park. Tourists had been assured by General Sherman that there was no danger; the

Indians would not venture into the Park. One tourist, John Shively, later recalled:

I was camped in the Lower Geyser Basin. I was eating my supper, and on hearing a slight noise, looked up, and to

my astonishment, four Indians, in war paint, were standing within ten feet of me, and twenty or thirty more had

surrounded me."

During the trek through Yellowstone, the Nez Perce had encounters with 22

tourists. In the Park two campers were killed. One, Richard Dietrich, was killed at McCartney's Hotel. McCartney used

an old bathtub as a coffin for Dietrich, there being no lumber with whch to construct a

proper casket.

In one group from Radersburg, Montana, there was a young couple, George and Emma Cowan, celebrating their

second wedding anniversay.

In the encounter with the Nez Perce, George, a lawyer, attempted to argue with the Indians. He was shot in a leg.

Cowan apparently remained hard-headed. Whereupon, one Indian then shot Cowan in the

forehead. The bullet bounced off Cowan's head but knocked him unconscious. His head was then pelted with rocks.

He was left for dead. Another member of the party, Albert Oldham, was shot in the face. The bullet

went in one cheek and out the other but missed Oldham's teeth and tongue. Oldham made good his escape into the

woods where he wandered for a day and a half with the only food being insects which he captured. The Indians then

forced the remaining part of Cowan's party including Emma Cowan to accompany them.

The party was ultimately released unharmed.

After several hours, Cowan came to and attempted to stand. A passing Indian shot him through the hip. Cowan fell face

forward into the dirt and was again left for dead. After the Indian left, Cowan attempted to stand but, with a bullet wound in

one leg and a wound in the opposite hip, he was unable to do so. Thus, Cowan crawled about four miles to where his

party had left their wagons. The only one at the wagons was his faithful dog Dido. With matches he found in the

remains of the wagons, Cowan was able to start a fire and made some coffee. The fire got out of

control and he managed to burn himself. For the next four days Cowan crawled twelve miles accompanied by

Dito until he was rescued. He was taken by wagon to Bozeman. One early visitor to the Park noted that the road was abysmal, that

there was a danger of one's conveyance sliding off the road and down the precipice along the top of

which the road was constructed. And so it was with the wagon in which Cowan was riding.

It overturned and pitched Cowan down the hill. Upon his arrival in Bozeman, Cowan was

carried up to a bed in a hotel. Upon being placed in the bed, the bed collapsed, pitching Cowan

on the floor. It has been said that Cowan uttered a few words to the effect that why didn't they

get the artillery and just finish him off. The Cowans did not return to the park until

1901.

Among those visiting the park at the time was the Earl of

Dunraven on his second trip to the park. The Earl and his party, however, did not

encounter the Indians. Several members of the earl's party, however accompanied the remainder

of the Cowan party to safety.

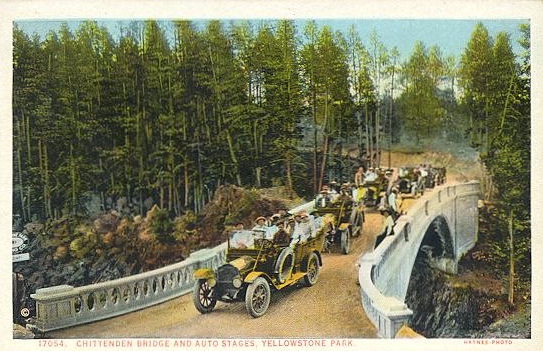

Chittenden Bridge, approx. 1918, Photo by Haynes

The original Chittenden Bridge was designed by Park

Engineer Hirem M. Chittenden and was constructed in 1902. At the time it was

the longest bridge of its type in the world. In 1914 its name was changed to

"Fishing Bridge." Chittenden subsequently was promoted to position of District

Engineer for the Seattle District of the U.S. Corps of Engineers where he was

responsible for, among other things, overseeing the design system for the Lake

Washington Locks. In addition to being an engineer he was the author of

American fur Trade of the Far West and an 1895 work on Yellowstone Park, both of

which are still used as source material today. Chittenden retired as a brigadier

general in 1910 and died in 1917 at age 59.

Next page: Yellowstone continued, roads

|