|

|

|

About This Site |

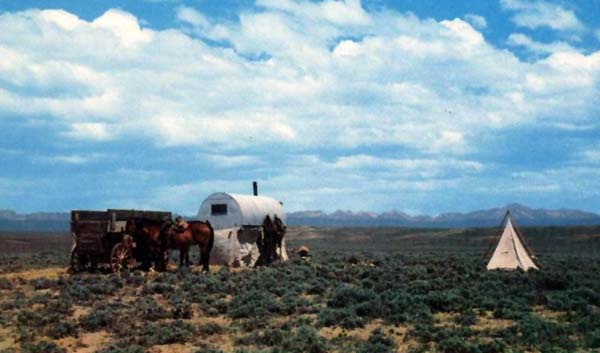

Two Bar Sheep Wagon

In addition to the Warren Livestock Company, some of the great cattle companies turned to sheep. Among them were the Swan Land and Cattle Co., LTD, owner of the Two Bar and the Pitchfork and Z Bar T made famous by Charles Belden's photographs.  A Pitchfork sheepherder in the Absorokas, 1920. Based on a photograph by Charles J. Belen.

Sheep Camp on the Z Bar T, 1920's, Photo by Charles J. Belden.

Sheep wagon, March 1940, photo by A. Rothstein

Sheep wagon, March 1940, photo by A. Rothstein After World War I, The woolgrowing industry in Wyoming began a slow decline. The decline was as a result of several factors including a reduction in protective tariffs and an increase in homesteading. Sheep growing required large areas of free range with as much as ten acres required for each sheep sheared. Homesteading broke up large continquous tracts of free range and, thus, woolgrowers were required to pasture smaller flocks. Larger woolgrowers bought or leased pasturage. Smaller growers were eliminated. Indeed, by 1920 most woolgrowing was eliminated in eastern Wyoming.  Sheep, approx. 1936.

Sheepwagon, 1960;s.

Chamber of Commerce Office, Buffalo, undated.

Sheep, U.S. Rte. 30, 1941, photo by J. Baylor Roberts And yet although the sheepgrowing industry has faded and many of the shearing sheds have fallen into rack and ruin, on short-grass plains traces of the lives of the lonely sheepherder may still be seen. Across Montana, the Dakotas, eastern Oregon, and Wyoming on distant ridges and buttes occasionally will be observed cairns, called by some "rock johnnies." They at first may remind one of cairns seen in northern Scotland. They are sheepherder's monuments constructed by sheepherders in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when sheepherding was a major industry. Writers now disagree as to the purpose of the monuments, did they serve as a guide or signpost pointing to water, or were they constructed to relieve lonliness? Both hypothesises have been put forth. Cope in "Sheep-Herder vs. Cow-Puncher": All over the sheep country in the mountains you may see what are locally known as "herder's monuments"; they are piles of stones which have been slowly gathered by the herders and built into fantastic forms, the attempts of the men to save themselves from the insanity that comes from perfect idleness. Frequently they find the bleached bones of a man on the bench lands, a herder who has yielded; whose mind has given way under the strain of the great wastes and the life with the band; who has shot himself. His band has wandered away, dropped over a precipice, or coalesced with some other band.

Sheepherder's Monument, Sweetwater County.

Sheepherder's Monument, 1942, photo by John Vachon

Icelander vörđur

"I builded me a Monument

"It stands just south of Punkin Butte

"No, it'll not be lonesome for me;

"And the Kiote will sing his song

From Shipp, E. Richard: Inermountain Folk Songs of their Days and Ways;

|