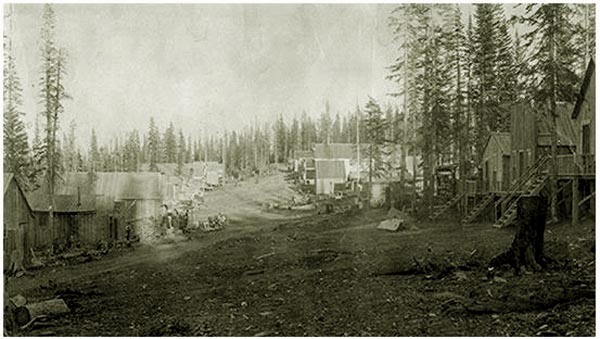

Battle, approx. 1904

The mines in the Battle Lake Mining District for the most

area are for the most part remembered in the name of creeks and gulches in the area, Doane Creek, Haggerty Creek.

The townsite of Battle is on the Continental Divide. As a result of its elevation, Battle like the other towns in the

District was bit cool in the winter.

On the left is the Thomas-Dillon Store, Battle, Wyoming, approx. 1902. The store

house the United State Post Office.

The Thomas-Dillon Store was owned by James M. Thomas, Jr. and Albert Dillon. The two were brothers-in-law and established the store about

1900. Along with W. J. Russel and various investors from Nebraska, that had an interest in the Russel Copper Minng Company wwhich had claims near

Cow Creek which was alleged capitalized at $1,000,000. Thomas also had an interest in the Mollie Stark Copper Mining Company. The store

was a general store selling everything from mining equipment to groceries. .

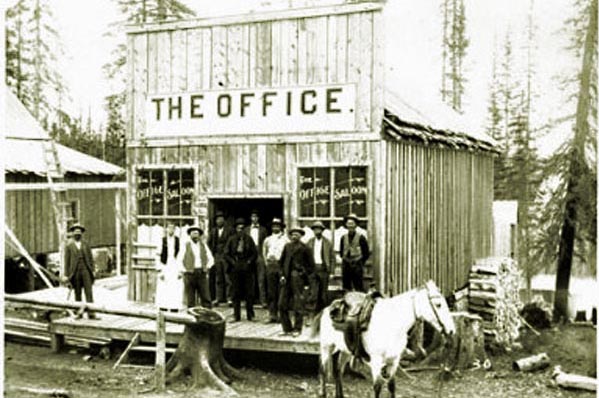

Battle, Wyo., the Office Saloon, approx. 1902

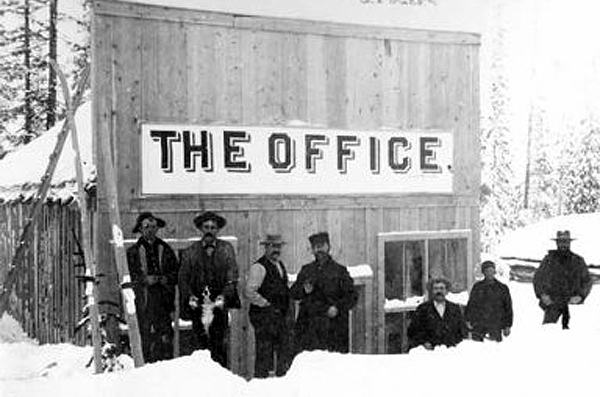

The amount of snow falling at Battle is indicated by comparison of the above photo with the following.

Battle, Wyo., the Office Saloon, Winter, approx. 1902.

With the closure of the mines, the towns rapidly declined. By 1906, the two Thomas and Dillon had unsatsified judgments against them. By 1909, the three towns of

Battle, Dillon and Rambler were esentially ghost towns. In 1909, the Right Reverend N. S. Thomas, Bishop of Wyoming, made a pastorial tour of the state. In an article, "First Impressions of Wyoming,"

Spirit of Mission, 1909, he wrote:

At Battle, where we had expected to hold service, we found a veritable deserted

village. Not even a yellow dog yelped at us as we entered. Through an open door I saw

snow three or four feet deep over a broken-down bed, and without was a snowdrift fully

thirty feet deep. This was on July the twelfth.

Battle, Snowshoe Party, approx. 1904

Almost immediately to the east of

the Divide, the old Battle-Encampment Wagon Road crossed the beginning of

Nellie Creek. Down the creek were many of the lesser mines of Battle including the Morris Mine, the Continental Copper Mining Co. properties, and

the Eagle Copper Mining Co's Gertrude Mine. The Gertrude was 3/4th of mile downstream from the Wagon

Road. Allegedly, "free gold;" that is visible gold particles, was found in some of the ore from the Gertrude.

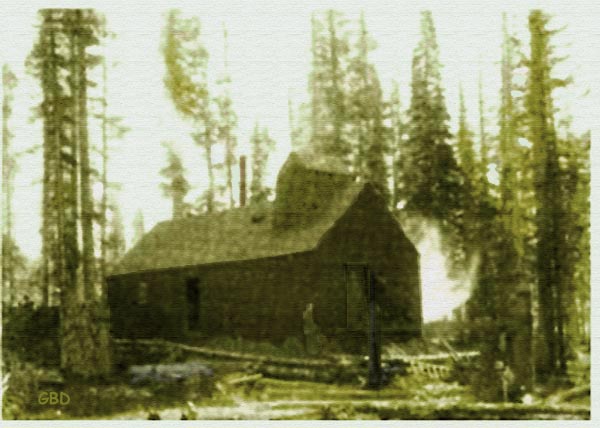

Shaft House, Gertrude Mine, Nellie Creek, 1903. As befitting a ghost mine, a

spectral figure may be seen in the doorway. Art Work by Geoff Dobson based on a magazine photo engraving.

For three years, 1903, 1904, and 1905, The Gertrude mine superintendent, Herman Ludwig, announced that during the ensuing winter season new machinery

would be installed in the mine. It, of course, was not to be.

After crossing a small divide from Nellie Creek, the wagon road

crossed the upper end of Hidden Treasure Gulch. The owners of the Hidden Treasure Tunnel Mine during the period 1902 to 1903 drove

a 925 ft. tunnel under the ridge connecting Battle to Rambler. Five shafts were driven. Two major veins of copper were hit, allegedly

containing 20 to 70% copper. Traces of gold and silver were also found. The mine, however, was not worked.

After Hidden Treasure Gulch, the road after crossin a minor divide came to Slaughterhouse Gulch. The gulch ran east and connected with the North Fork of the Encampment

River. The name "Slaugherhouse Gulch" is

found in a number of mining areas including Colorado, Idaho, the Black Hills, and California. Rumors abound in each that they are haunted. Thus rumors have circulated that

Wyoming's Slaughterhouse Gulch is haunted by a long ago miner who managed to blow himself up.

Dynamite is popularly regarded as much safer than the former ue of

nitrogycerin. A foolhardy method of demonstrating dyamite's safety is to set fire to it. It generally will burn but not explode. Nevertheless,

caution in its use must be observed. The powderhouse at the Rudefeha was designed to hold a carload

of dynamite. It had walls six feet thick filled with sand designed to preclude a stray bullet from setting of an

explosion. Even seasoned miners became careless. Dynamite would be set off by a blasting cap or cartridge containing fulminate of mercury.

The cartidge itself was set off by a fuse which was

crimped to the cartridge. Some miners rather than using a crimping tool, crimped the cartidge to the fuse using

a jack knife or with their teeth. A miscalculation could do great damage to one's face. The fulminate of mercury is sensative to friction and

could thus be set off by merely twisting the fuse rather than setting it in straight. M. A. Kelley, a seasoned miner working at the Sndicate mine was

killed in pulling out a bad shot which had failed to go off.

At the Haggerty, two miners were killed. Thus it has been speculated that the ghost in Slaughterhouse Gulch is that of a miner who blew himself

up with a bad shot or a bad crimp.

The rumor of an apparition in the Gulch dates back to the days of the Scribner Stage Line.

It has been contended that one driver for the Stage Line quit after the

spectre frightened his horses. About 1917, two Forest Rangers, John C. Peryam and Horace B. Quivey were marking trees for the

Forestry Service. Peryam was the son of William T. Peryam who had settled along the North Fork of the Encampment about 1891.

At some point Peryman's wife, and his sister Dorothy

joined the two men maybe bringing them dinner. As the four sat down to eat their supper, an apparition came down the road. His footstep made no sound. Not did the figure

appear to notice the four and said nothing. In the loneliness of the Gulch this was highly unusual.

The spectre disappeared.

. . . . . .

Left, Horace B. Quivey; Right, John C. Peryam

With the war, Peryam and Quivey had attempted to enlist in the army, but permission had been denied by the Forestry Service. Finally, permission was granted.

On January 24, 1918, Horace and Dorothy were married. John was best man and John's wife served as the bridesmaid. The next day both enlisted. Seven days later both Horace and

John were mustered in. Horace was

assigned to Company A, 7th Battalion, 20th Engineers (Forestry), the "Lumber Jack Regiment."

John was assigned the 19th Company, 20th Regiment of Engineers. Two and one-half months after enlistment,

Dorothy was left a widow. John was dead at St.Nazaire, France, and was interred in American Base Cemetery No. 21, in France. In 1922, his remain were

disinterred and returned to the United States for re-interment at Garland, New York. With the end of the War, John returned to the United States and was

mustered out at Fort D. A. Russell on January 10, 1919. Dorothy later remarried a civil engineer, W. G. Shapcott. She died in

1980 in San Diego, California. So Gentle Reader, as you pass by Slaughterhouse Gulch, think of a young Forest Ranger who gave his life

for our country in far off France.

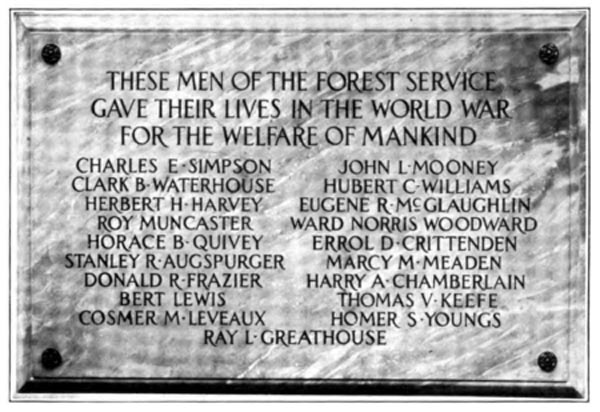

Memorial Plaque to Forestry Service employees who gave their lives in the Great War, Washington, D. C., 1919..

In 1998, The Wyoming State Geologic Survey, noting that the New Rambler mine

had in the early 1900's, in addition to copper, mined some platinum-group metals (PGM), reported

that there has been some renewed interest in exploration and claim staking for

PGM in the state.

The renewed interest is borne out by the application of

Broken Arrow Mining, LLC to conduct exploration at the Lost Cabin Mine site in the former

Grand Encampment Mining District. The site, itself,

dates back to 1899. The company proposes to examine minerals in the existing pits. A draft

environmental impact statement was issued in October of 2003. A portion of the

proposal would require a limited reopening of the historic road to the site, but only for

employees of the Company.

The Lost Cabin Mine is not the legendary Lost Cabin Mine in the Big Horn Mountains. Just as Arizona has

the Lost Dutchman's Mine in the Superstitions, Wyoming has its Lost Cabin Mine. According to the legend, in 1863, three men named

Cox, Jones and Herlburt were traveling east from Walla Walla and discovered a rich deposit of placer gold someplace in

central Wyoming. They constructed a small cabin and stockade and proceeding to

gather the gold. The cabin was attacked by Indians and only Herlburt escaped. He made his way

to, depending on the source, South Pass City or Fort Fetterman, with the news, but he was unable to find his way back.

Note: Fort Fetterman and South Pass City were not established until 1867. Again depending on the

source, the mine was either in the Wind Rivers, the Big Horns, or along Crazy Woman

Creek. Other embellishments are sometimes added to the legend. According to some, Jim Bridger while

guiding the Raynolds Expedition "rediscovered" the mine, but was sworn to secrecy by Reynolds out of fear

that all the men would take off to mine for gold. Bridger guided the Raynolds Expedition in

1858. It is, thus, difficult to conceive that Bridger could have rediscovered the mine before

it was originally discovered. Others claim that Father Pierre DeSmet, Roman Catholic missionary to

the Indians, knew the location of the mine.

But regardless of the uncertainty of location, in August, 1893, J. C. Carter, a prospector, arrived in

Casper with the startling news that he had found the long lost mine in the

Big Horn Mountains. Several citizens accompanied Carter back to the lost cabin and the mine. They turned out

to be an Indian hunting blind. Alfred Mokler in his History of Natrona County, R. R. Donnelly & Sons, Chicago, 1923,

noted that C. T. "Rattlesnake" Jones also claimed to have rediscovered the mine. Rattlesnake was so-called

from his proclivity of keeping rattlesnakes as pets. Mokler

recalled an occasion when Rattlesnake gave an exhibition of his pets on the

floor of Kimball's drug store. According to Mokler, "A man could step into the adjoining Wyoming

saloon, take a few drinks of squirrel whiskey and without waiting for the slow

action of the booze, could in two staggers fall into Kimball's store and see the

snakes." [Writer's note, "squirrel whiskey," a homemade whiskey made with excessive amounts of sugar, guaranteed to

give a splitting headache.] Thus, if there ever was a Lost Cabin Mine, it remains lost.

By the mid-1930's Battle had faded away.

Battle, Wyoming, mid-1930's.

Next page: Silver Crown Mining District.

|