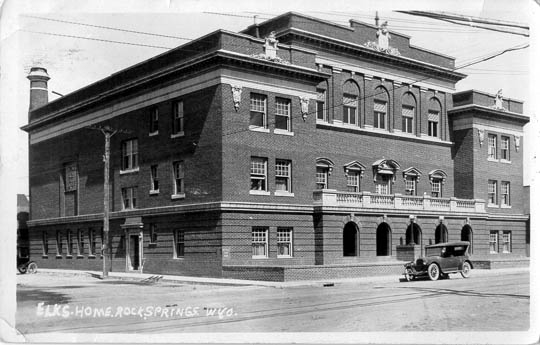

Rock Springs Elks Lodge No. 624, 1920's.

The Elks Lodge, located at the corner of C and 2nd Streets, was constructed in

1924. The building, on the National Historic Register, was designed by

local architect Daniel D. Spani. Spani also designed the Security State Bank Building at

502 S. Main, also on the Historic Register. Prior to moving into the above building,

the Lodge was located in the building depicted in the next photo.

Elks Lodge, 1912

In addition to the Elks Lodge, other lodges included the International Order of Odd Fellows, see next page, and

Slovene Lodges. In the early 1900's, over 50 different nationalities were represented in

Rock Springs. Many were from the Austro-Hungarian Empire which in those days included what are

now Croatia, Bosnia, and other parts of the Balkins.

Chief among the immigrants in Rock Springs, following the exodus of the Chinese, were the Slovenes. In 1912,

the Reverend J. M. Trunk in his History of

Slovene Communities reported that the Slovenes in Rock Springs had formed

five lodges including St. Allysius with 303 members, St. Joseph with 65, and Heart of

Virgin Mary. Slovene Lodges existed in many of the western mining towns and

received their start in the 1880's providing not only fraternal fellowship but

affordable insurance. Chief among the Slovene fraternal orders, and still in

existence today, were the KSKJ (Kranjsko Slovenska Katcliska Jednota,

Carniolan Slovene Catholic Union) now known as the American Slovene Catholic Union,

and the SNPJ (Slovenska Narodna Podporna Jednota, Slovene National Benefit

Society) which today has a national membership of approximately 44,000.

Excelsior Lodge No. 9, Odd Fellows, Band, approx.

1939

Rock Springs is unusual in that the Slovene Lodge Building at 513 Bridger Ave., the Slovenski Dom, the

Slovene National Home, constructed in 1913, remains in use and still serves as

a social center of the community. The Slovene Lodges have been very supportive of the

Roman Catholic Church. Our Lady of Sorrows Church can trace its history back to

1887 and the assignment of Fr. Delahunty to the parrish. By 1910, the church had 2 pastors,

the Rev. Francis J. Keller and the Rev. Anton Schiffrer. The Rev. Keller primarily ministered to

the English speaking congregation and the Rev. Schiffrer to the non-English speaking who lived on

the north side of town. Until 1920 when a rectory was built, the Rev. Schiffrer resided in

a coal bin in the basement of the church. The Slovene lodges provided funding for an expansion of the church, but ultimately with

most of the congregation living on the north-side, a second church, Saints Cyril and

Methodius was constructed, eliminating the dangerous crossing of the tracks.

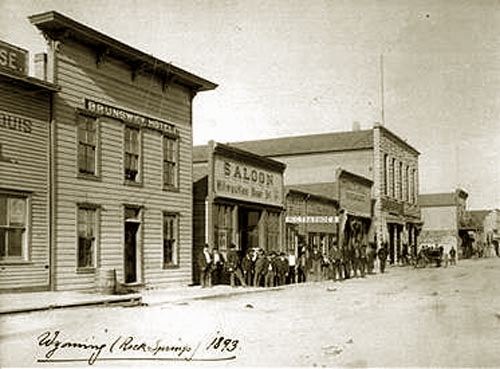

North Front Street

Brunswick Hotel, Rock Springs, 1893

The national media has made it seem as if Rock Springs continues as a "Wild West" town where the customers are lined

up outside the saloons as in the above photo. The reputation developed in the 1970's with a nationally broadcast

60 Minutes program in which it was contended that on "K" Street saloons and other

establishments were wide open. As a result of the allegations and embarassement, the City brought in a new

director of Public Safety, former range detective Edward Lee "Ed" Cantrell. A special grand jury was

convened to look into the allegations, and Cantrell brought in from Gillette a Puerto Rican undercover agent from

New York, Michael "Mike" Rosa. Rosa, looking much like a disheveled, shaggy Geraldo Rivera, was soon frequenting, in his

role as an undercover agent, the various saloons of the town. How undercover Rosa was may be a matter of question. He

was almost universally disliked by his fellow police officers, and had openly bragged that he was

going to "bring down" Ed Cantrell in forthcoming testimony before the grand jury. There were also allegations

that Rosa had been paying off informants with drugs from the evidence room.

As a result, Ed Cantrell decided on a talk with Rosa. Cantrell with two other officers pulled up outside

a lounge on Elk Street near the interstate. Rosa emerged wearing a hostlered gun and carrying a glass of wine.

Rosa got in the backseat of the car. Cantrell was in the passenger front seat. During the course of the

conversation, Rosa called Cantrell a "m***** *****r" and arched back as if he might have been going for

his gun. His hands were allegedly free, the glass of wine held between his legs. A shot rang out, and Rosa lay dead in

the backseat, a bullet wound from Cantrell's gun betwen Rosa's eyes, Rosa's gun still holstered, and his hands around

the wine glass.

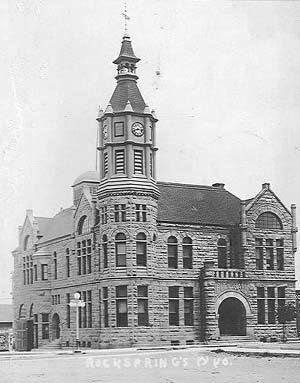

Rock Springs City Hall, 1910

Ed Cantrell was, of course, charged with first degree murder. In the words of a

Supreme Court justice, media attention at the preliminary hearing was "massive." The

judicial proceedings were to the media as chum is to sharks. KTWO in its desire to obtain all of the

evidence, whether admissible or inadmissible, even sued the committing magistrate. Indeed,

the media publicity has continued to this day with further exposes repeated on cable channels. The exposes would show

endlessly repeated photos of the old City Hall and the motel parking lot where the deed occurred.

Cantrell's initial lawyer, Robert E. Pfister from Lusk, brought in colorful Dubois lawyer and former

Fremont County prosecutor Gerry Spence for the defense.

Venue for the trial was moved to Pinedale in neighboring Sublette County, a location believed by some to favor the defense.

Yet there was an overwhelming problem: Cantrell was seated in the front seat. How could

Ed Cantrell, seated, get his weapon out of his holster, and shoot Rosa if in fact Rosa was attempting to

get his gun? What defense could there possibly be? Even Spence in his book

Gunning for Justice confessed that when he was first called by Pfister, he,

Spence, initially believed from the media reports that Cantrell was an "assassin."

In trial practice, lawyers frequently save the best witness for last and will ocassionly make a "show."

Juries remember best that which they heard first and that which they

heard last. Thus, the media frenzy continued. Spence called as his last witness, a former border patrolman, National Rifle Association shootist,

and author of the book No Second Place Winner, Bill Jordan. Spence received permission for

a court room demonstration. A gun was loaded with blanks and a young deputy was told to point the gun at

Jordan and if Jordan made any move towards his gun to pull the trigger. All of a sudden a shot was fired in the

courtroom. The deputy stood there chagrinned, the deputy's weapon still unfired. Jordan testified that the

normal human reaction time is 1/2 second, but he, Jordan, had trained himself to draw and fire in 0.27 seconds, less than

half the time for someone else merely to recognize that an opponent is going for his gun. "Q. And what about Sheriff Cantrell?"

"Ed? Well, I reckon he's a mite bit faster'n me."

The jury found Ed Cantrell not guilty. A cheap trick? Perhaps. But in all fairness, it must be said that under

Wyoming law (actually the law of most states) it was not necessary that Rosa was actually going for his gun, only that Cantrell reasonably believed that he was.

As noted by the Wyoming Supreme Court in Hernandez v. State, 976 P. 2d 672 (Wyo. 1999):

[T]he right of self-defense exists whether the threatened danger is real or

apparent and that it is not necessary for the danger to be real or

impending and immediate before self-defense is justified as long as the

defendant reasonably believes it is.

Thus, even if Rosa were merely going for his wine glass, if Cantrell reasonably believed

that Rosa was going for his gun, Cantrell was not guilty.

The Hernandez case involved a drug deal gone bad outside a Rock Springs saloon. In Hernandez, the jury did not

accept the defense, but in the Cantrell case the media acted as if they were cheated out of the expected result. But as

later pointed out by Mr. Justice Raper of the Wyoming Supreme Court:

One of the best examples that news stories very likely have little,

if any, effect on the trial outcome is the case out of which arose

Williams v. Stafford, supra, State v. Edward L. Cantrell, of which

judicial notice may be taken. The news coverage was massive with respect

to the preliminary hearing. The news items disclosed evidence both

favorable and unfavorable to the defendant, including what was probably

evidence inadmissible at the trial. The trial judge changed the venue.

The defendant was acquitted, eliciting further reporting and editorial

comment over an apparently unexpected outcome. What the public sees,

hears, reads and believes and what the jury sees, hears and holds are

two entirely different pictures.

State ex rel Feeney v. District Court, 607 P. 2d 1259 (Wyo. 1980), dissenting opinion.

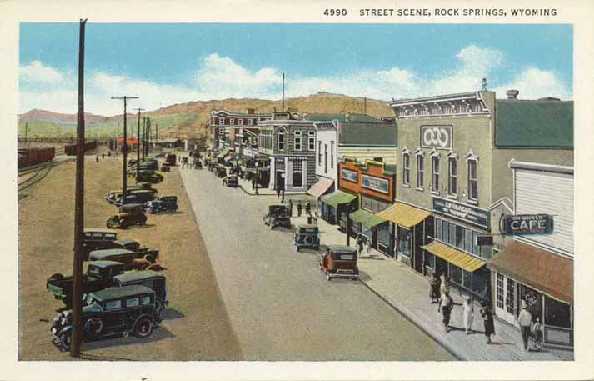

Rock Springs, 1930's

The Slovenes were, not, however, the first ethnic group to inhabit Rock Springs. As discussed with regard to

Coal Camps, by 1885, Chinese constituted the largest population group in the area. In September of that year,

festering resentment boiled over at Pit Number 6, resulting in the massacre of a number of

Chinese and the burning of their houses. The resentment was as a result of a belief that the

Chinese were keeping the wages down and by a favorable assignment of work at Pit Number 6 to the

Chinese.

Next page: Evanston

|