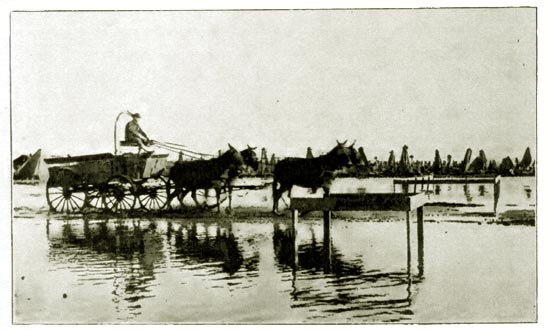

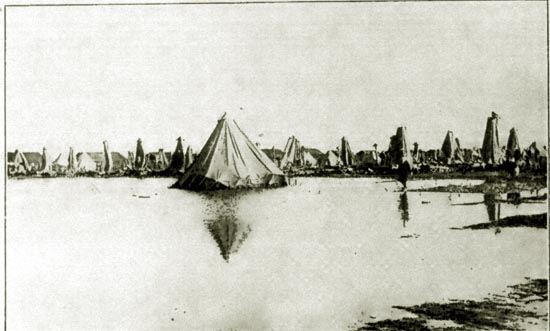

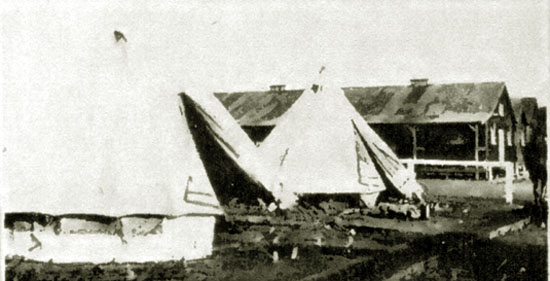

Camp Mills, Long Island, the day battery F (old Company C) arrived.

In early December the boys from old Company C, now known as Battery F, arrived at Camp Mills, Long Island.

Conditions were miserable. It continually rained, snowed or sleeted. There were no drainage facilities and water ran down the camp

streets almost six inches deep.

it was in the winter and there was no adequate means of

providing warmth. There was no mess hall. The kitchen was under a crude shelter looking much like a pole barn. The lads had to carry their

mess kits back to their tents to eat. The kits would fill with the rain.

The water pipes were frozen half the time. There was no bath house and the only means of taking a bath was to

heat a bucket of water and take a sponge bath in one's tent or wait until one could get a pass and go into town to a public

bath house.

Camp Mills, Long Island, December, 1917.

There was, of course, a saving grace. The camp was convenient to New York City and passes were given liberally. As explained by Paul M. Davis and Allen W.Hale in their

1919 History of Batter"C", 148th Field artillery, passes were given out on

Saturday at one o'clock, enabling those that received a pass to be absent from Saturday at One o'clock to Monday at Reveille. The good

times in New York were not described, "for every one knows what an enjoyable time

one can have in that gay city."

On December 13, a blizzard struck. By the time reveille sounded the next morning, the high winds roaring off Long Island

Sound and weight of the wet snow

had collapsed most of the tents in the camp. Some soldiers had to be dug out from beneath their collapsed tents.

The regiment was formed up, marched to the Long Island Railroad which took it to

ferries. The ferry boats carried the men down the East River and around to Jersey City.

Trains then carried the troops to Cresskill. From there they marched

through deep snow to newly completed Camp Merritt.

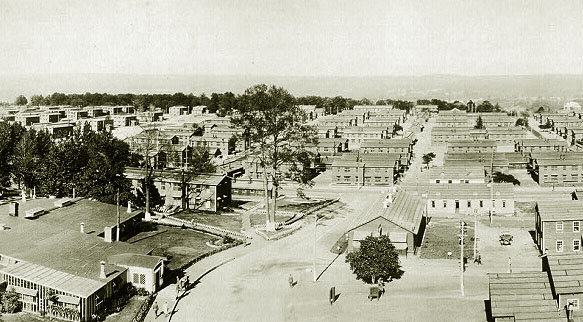

Camp Merritt

Camp Merritt was a sharp contrast to Camp Mills. The men were housed in two story barracks which actually had heat. The Red Cross, the

YMCA, and the Knights of Columbus all had facilities to help provide for the men pending being shipped out. The 148th was to depart at the same time

as the 146th from Idaho. A rash of measles and mumps broke out amongst the 148th. They were therefore held in quarantine until the outbreak subsided.

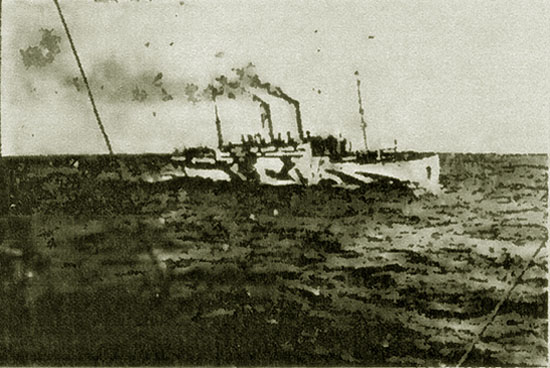

The 148th finally embarked on January 13, 1918, on board the "two stacker" White Star Liner

Baltic accompanied by the Cunard liner Tuscania. The Tuscania was done up in "razzle-dazzle." Razzle-dazzle was a method of

camouflage designed to disguise the size and lines of a ship making use a submarine range finder difficult.

The two ships proceeded to

Halifax where they joined a convoy of ships protected by Royal Navy destroyers on each side of the convoy. The destroyers were lined up much like flankers along side a

trail herd of cattle. A cruiser, the H.M.S. Cochrane rode point and an American heavily armed collier, the U.S.S. Kamawha rode drag.

Conditions on board for the enlisted men were miserable. Of course, the North Atlantic in winter is automatically miserable. Even today there is only

one ocean liner in the world specifically designed to handle the heavy seas of the North Atlantic, the

Royal Mail Ship Queen Mary 2, equipped with multiple stablizers, deeper and heavier hull, and pointed sharp bow fitted with a break water designed after that of the

great French Line ship Normandy. Needless to say, the Baltic was considerably smaller that the Queen Mary 2. Stablizers had not yet been

invented and the ship was considerably slower. Officers were housed in Second Class cabins. To the extent that Third Class cabins were available they were utilized by

non-commissioned officers. Mess might consist of steam cooked unsalted potatoes, fish and cheese, or sometimes "slum," a watery

stew somewhat akin to the old S.O.B. stew served on cattle drives or roundup. The term "slum" was

derived from "slumgullion," the term given by cowboys to the slimey, yellowish sludge left over from mining operations.

the Tuscania in razzle-dazzle garb. Photo taken from deck of the

Baltic, 1918.

The enlisted men bunked in the hold. Ventilation in the hold was provided by a canvass tube leading down from the

Deck. There were no bathing facilities. On board the Tuscania the men were bunked in pens previously used for cattle or horses. Seasickness was prevelent. The smell was awful.

A day out from Halifax the temperature on deck was twenty degrees below zero. After the Gulf Stream was finally hit, it warmed up a bit, and many of the men moved to the deck.

Twice a day, the Regimental Band would play. At night, the convoy was blacked out, the convoy visible only as

dark shapes against the North Atlantic sky.

When the convoy reached the "Danger Zone," more ships from the Royal Navy joined in protecting the convoy. The captain stayed on the

bridge, taking his meals there and possibly sleeping there.

One passenger on board the >i>Baltic, Irvin S. Cobb, later wrote in the

Saturday Evening Post, March 9, 1918:

It was a crisp bright February day when we neared the coasts of the British Empire. At

two o'clock in the afternoon we passed, some hundreds of yards to starboard, a round,

dark, bobbing object which some observers thought was a floating mine. Others thought if

might be the head and shoulders of a human body held upright in a life ring. Whatever it was,

our ship gave it a wide berth, sheering off from the object in a sharp swing. Almost at the

same moment upon our other bow, at a distance of not more than one hundred yards from the

crooked course we were then pursuing, there appeared out through one of the swells a lifeboat,

oarless, abandoned, empty, except for what looked like a woman's cloak lying across the thwarts.

Rising and falling to the swing of the sea it drifted down alongside of us so that we could

look almost straight down into it. We did not stop to investigate but kept going, zigzagging

as we went, and that old copy cat of a Tuscania came zigzagging behind us. A good many persons

decided to tie on their life preservers.

On February 5 at about twilight, on the starboard side the distant shore of Northern Ireland was seen. In the distance, the

lighthouse could be seen. The convoy was making about 12 knots. About an hour later seven miles north of the Rathlin, Light,

a noise described as similar to "a boy dragging a stick along a picket fence" was heard.

It was later believed to have been a torpedo scrapping along the side plates of the ship. A few moments later,

a card game was interrupted by an American officer, "Better come along, you fellows, * * * Something has happened. The Tuscania -- she's in trouble."

The U-Boat U-77 had fired two torpedoes. The first had missed and had scraped along the hull of the

Baltic. The second found its mark in the center of the Tuscania. Most of the men were rescued by the

H.M.S. Mosquito, the H.M.S. Grasshopper and various fishing boats and trawlers. About 205 men and members of the

crew were, however, lost. From the stern of the Baltic the signal lights and rockets of the dying ship could be seen.

Pursuant to orders, the Baltic steamed on.

The next day, the Baltic arrived in Liverpool. A month before, units from th North Dakota National Guard had arrived at Liverpool and were

unimpressed. From Liverpool, the 148th was taken by tain to Winchester and the

Amrican rest camp Winnall Down, three muddy miles from the train station. For the first time in a month, the men were able to

bathe. After two cays at Winnall Down and seeing the sights in Winchester, the boys proceeded to

Southhampton for transport to Le Havre on the H.M.S. Prince George, an obsolete dreadnaught on maintenance and sickbay status.

H.M.S. Prince George.

Although, the Channel Coast is the "Mediterranean of

England" complete with palm trees, once past Spithead, the Channel in the winter can be a bit rough cutting off France. The trip across the Channel again visited

seasickness upon many of the troops. As expressed by Paul M. Davis and Hubert K. Clay in their 1919 History of Battery C,

"The sea is running high and the ship is tossed about like a cork. The men are packed like sardines, without sleeping quarters.

Everybody without exception becomes violently sick."

At LeHavre, the soldiers were greeted by four French boys singing "It's a Long Ways to Tipperary."

The American Rest Camp at LeHavre, 1918.

From LeHavre, the 148th proceeded to Camp de Souge near Bordeaux for training on the giant G.P.F. (Canon de 155 Grande Puissance Filloux) heavy artillery.

The Filloux 155 mm. guns had a 19 foot barrel and were capable of firing a steel shell 16 kilometers. One former officer of the

148th, William R. Wright, in a letter to the editor New York Tribune, September 23, 1921, noted:

The G.P.F 155 mm. gunsthat went through all these battles were manned by volunteer Western

college men and cowpunchers, the majority of them never having seen the sea before embarking for France. They

were horsemen, but in manning the first G.P.F. regiments in France and fighting every day through the major operations and during

seven months in Germany as the sole representatives of this able type of artillery, enjoyed the added

distinction of being the first motorized regiments of artillery in France. After transferring

their affections from the horse to the tractor they tained the C.A.G. units that later came into the line.

Camp de Souge, 1918.

As indicated, the 148th was the first motorized artillery regiments. Thus at Souge, some trained in driving

the monster trucks and tractors used to pull the cannons, while others trained on using the trucks. Nevertheless,

baseball diamonds magically sprang up.

Regimental Championship Baseball team, Headquarters Company, Camp de Souge, 1918.

In early May, the 148th was transferred to Castillon to complete training. On the Fourth of July, the Brigade entrained for the

Chateau-Thierry Front.

Music this page courtesy Horse Creek Cowboy:

It's A Long Way to Tipperary

Up to mighty London came

An Irish lad one day,

All the streets were paved with gold,

So everyone was gay!

Singing songs of Piccadilly,

Strand, and Leicester Square,

'Til Paddy got excited and

He shouted to them there:

It's a long way to Tipperary,

It's a long way to go.

It's a long way to Tipperary

To the sweetest girl I know!

Goodbye Piccadilly,

Farewell Leicester Square!

It's a long long way to Tipperary,

But my heart's right there.

Paddy wrote a letter

To his Irish Molly O',

Saying, "Should you not receive it,

Write and let me know!

If I make mistakes in "spelling",

Molly dear", said he,

"Remember it's the pen, that's bad,

Don't lay the blame on me".

It's a long way to Tipperary,

It's a long way to go.

It's a long way to Tipperary

To the sweetest girl I know!

Goodbye Piccadilly,

Farewell Leicester Square,

It's a long long way to Tipperary,

But my heart's right there.

Molly wrote a neat reply

To Irish Paddy O',

Saying, "Mike Maloney wants

To marry me, and so

Leave the Strand and Piccadilly,

Or you'll be to blame,

For love has fairly drove me silly,

Hoping you're the same!"

It's a long way to Tipperary,

It's a long way to go.

It's a long way to Tipperary

To the sweetest girl I know!

Goodbye Piccadilly,

Farewell Leicester Square,

It's a long long way to Tipperary,

But my heart's right there.

Additional verse as sung by soldiers in France

That's the wrong way to tickle Mary,

That's the wrong way to kiss!

Don't you know that over here, lad,

They like it best like this!

Hooray pour le Francais!

Farewell, Angleterre!

We didn't know the way to tickle Mary,

But we learned how, over there!

Next page: The 148th Field Artillery continued, at the Front and return home.

|