Split Rock, William Henry Jackson, 1870.

Along the Sweetwater at the top of the Rattlesnake Range is a cleft known as Split Rock which provided another landmark

for the early traveler. Nearby along the river was established an early Pony Express Station

known as Sweetwater Station. The original station lasted about a year and was replaced by the

Split Rock station. Split Rock station was replaced by a fortified stage and telegraph station also known as Sweetwater Station.

At Split Rock, William Henry Jackson, 1870.

Professor Countant described one such attack on the station and the reason for moving the stage line further south:

Holliday had been busy during the winter and spring, stocking up the line, distributing

additional men, horses and stores at the different stations in Wyoming, and all things were in

readiness for business when in March, like a thunderclap from a clear sky, the Shoshone tribe

which had for so many years been peaceable and friendly to the whites, made a descent

simultaneously on the stage stations from Platte Bridge, just above Caspar, to Bear River

Station, where Evanston now stands, and captured every horse and mule belonging to the company.

The coaches containing passengers were left standing at stations and between stations.

The Indians refrained from killing anyone except at the station of Split Rock, on the

Sweetwater. Holliday had brought to that place a Pennsylvania colored man who spoke only what

is called Pennsylvania Dutch. This man was the cook at the station. The Indians who were

gathering up the stock reached Split Rock and concluded that it was a good opportunity to

get something to eat, and selecting one of their number who could speak English, instructed

him to direct the negro to prepare dinner for them. The order was given in fairly good English,

but the negro failed to understand. The native linguist then tried French and followed it with Spanish, but none of these languages were understood by the trembling cook and things began to look serious. After a brief consultation among the Shoshones, they decided that the negro was bad medicine, so they killed him on the spot. Near the Devil's Gate Station they met the west bound coach, which contained, besides some passengers, Lem Flowers, an agent of the company, also two other employes, Jim Reed and Bill Brown. A demand was made on them for the horses, which they refused to give up, and a fight ensued which resulted in the wounding of the three men mentioned. They finally gave up the horses, and the Indians were content to go away. This attack on the stage line by the Shoshones resulted in the stoppage of all stages in Wyoming. President Lincoln was appealed to, but having no troops who could reach the scene of Indian depredations under two months, made a personal appeal to Brigham Young to send troops for the protection of the mails. In response to this request, Young sent what was known as the

Mormon battalion. It consisted of 300 men under the command of Lot Smith. Headquarters being

established near Devil's Gate, details of twenty men were made to guard different points on the

road. New stock was furnished by the stage company, and by the time the stages were again

ready to move, the Sioux in eastern Wyoming and western Nebraska started out on their regular

spring campaign of murder and plunder.

Sweetwater Station, water color, William Henry Jackson.

In the distance is Split Rock. Closer to the viewer is the stage and pony express station. The foreground is abuzz with activity. A pony express rider doffs his had

to the passing Overland Stage. Behind the stage is an ox-drawn freight wagon. A bullwhacker, walking beside the left wheel ox, guides the team. Heading

in the opposite direction is a mule-drawn Murphy wagon. The muleskinner is riding the left

wheel mule. Indians with travois are carrying their goods. A trapper walks behind his burro followed by his

dog. In the lower right, pack mules carry their loads.

The scene was painted in the 1930's by William Henry Jackson (1843-1942). Jackson came west in

1866 and was employed on the Oregon Trail as a bullwhacker. As discussed on a later page,

Jackson was employed as the photographer for the Hayden Expedition. The painting represents a period

earlier than Jackson's time on the Oregon Trail but was painted from a combination of Jackson's memory and

his early photographs. Beginning in 1930 through 1940, Jackson did a number of water color paintings

illustrating the early Oregon Trail. Sixty-three of those drawings and paintings are on display at the Scott's Bluff National Monument.

Jackson, following

service in the Union Army, received training in photography at the Styles

Studio in Burlington, VT. After breakup of his engagement to be married, he

headed west and was employed for a short time on the Oregon Trail as a bullwhacker before establishing

a photographic studio in Omaha.

Later, Jackson recalled his experience as a bullwhacker by noting that after several months

he wore two pairs of trousers because fortunately the holes were in different places and,

thus, protected his modesty. He also noted that prior to the experience he never used

profanity, but at the end of the job, his vocabulary had changed. Bullwhackers were,

however, noted for their use of language.

Two days past South Pass, a broad valley twenty miles wide, the trail split at a point known as the

Parting of the Ways. The left trail lead

to Fort Bridger and Utah and California. The right-hand trail, known as the Sublette Cutoff, lead to Fort Hall and Oregon.

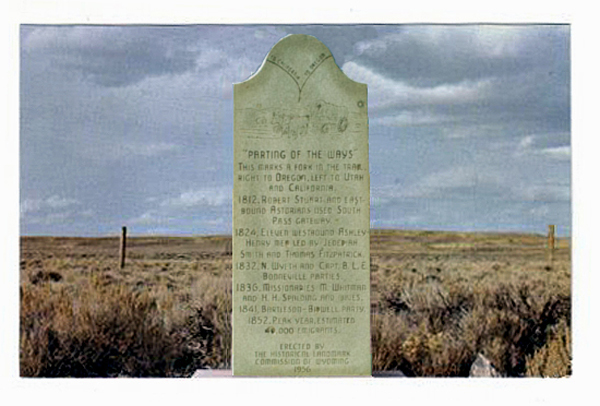

Monument marking the "Parting of the Ways," State Road 28.

The Monument reads:

"PARTING OF THE WAYS"

THIS MARKS A FORK IN THE TRAIL

RIGHT TO OREGON. LEFT TO

UTAH

AND CALIFORNIA

1812, ROBERT STUART AND EAST

BOUND ASTORIANS USED SOUTH

PASS GATEWAY

1824, ELEVEN WESTBOUND ASHLEY-

H

ENRY MEN LED BY JEDEDIAH

SMITH AND THOMAS

FITZPARTICK

1832, N. WYETH AND

CAPT. B. L. E.

BONNEVILLE PARTIES

1841, BARTLESON-BIDWELL PARTY.

1852, PEAK YEAR ESTIMATED

50,000 EMIGRANTS

ERECTED BY

THE HISTORICAL LANDMARK

COMMISSION OF WYOMING

1956 |

The Sublette Cutoff reduced the time on the trail by about eight days, but at a cost.

It crossed a waterless desert and lengthed the distance to the next point of supply. Some question exists as to the true location

of the Parting of the Ways. It has also been contended that its true location is about another

eight miles to the west at a point accessible only on Jeep trails. It has also been observed that one could separate from

the Oregon Trail and continue to California at Fort Hall. Thus, many 49'ers continued on the

Sublette Cutoff because of the savings in time.

The party of emmigrants to use the Sublette Cutoff was the Stephens-Murphy Party captained by Caleb Greenwood and his two half-Indian sons.

Captain Greenwood, it is said, because of his many years living with the Crow had taken on Indian dress and manners and, thus,

at least one female member of the party had expressed the opinion that she was more terrified of

Captain Greenwood that of the Indians. Greenwood had participated in the Astoria expedition. Also acting

as a guide was 64 year old Isaac Hitchcock. Hitchcock had, allegedly, been a part of the

Bonneville expedition to California. In any event, the new cutoff suggested by Hitchcock followed the

same route as previously used by the Bonneville expedition. The Sublette Cutoff remained in general use, however,

only until 1859 and the opening of the Lander Cutoff. Thereafter, it was in use only by those going to Salt Lake City.

The Lander Cutoff was shorter and had wood and water.

"True" Parting of the Ways

Those crossing the desert noted the increasing quanties of dead cattle along the road. David Dinwiddie in another

1853 wagon train from Indiana, observed in his diary:

"Perfect desert, sand and sage. Near Dry Sandy Creek. Fine view of snow in

the mountains. At junction of Great Salt Lake and Fort Hall Roads.

Saw 15 dead cattle today."

Big Sandy Crossing. To the right in the photo, the ruts going up the bank of the

river in a reverse "S" fashion may be seen.

Near present day Farson, the pioneers crossed the Big Sandy.

The area near Big Sandy was described by Joel Palmer in his 1845 Journal:

"July 20. This day we traveled about thirteen miles, to Big Sandy.

The road was over a level sandy plain, covered with wild sage.

At Little Sandy the road forks—one taking to the right and striking Big Sandy

in six miles, and thence forty miles to Green River, striking the latter some

thirty or forty miles above the lower ford, and thence to Big Bear River, striking it

about fifteen miles below the old road. By taking this trail two and a half days' travel

may be saved; but in the forty miles between Big Sandy and Green River there is no water,

and but little grass.

Scene near Big Sandy

Capt. Stansbury in his diaries, noted that in the course of one day's twenty-four mile march he observed the relics of

seventeen wagons and the carcasses of twenty-seven dead oxen.

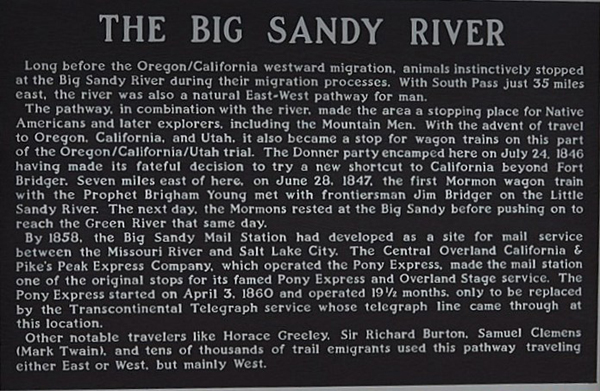

Historical Marker at the Big Sandy.

In 1858, Congress appropriated funds for the construction of a new wagon road leading from the last crossing on the

Sweetwater and proceeding along the southern edge of the Wind Rivers and crossing the

Green River near Big Piney. From there it crosses present-day Lincoln County and leaves Wyoming near Afton. The new road,

constructed in 90 days, shortened the journey by nearly seven days and provided ample supplies of wood, water, and grass.

The Lander Cutoff remained in general use until about 1912.

Next page: The Pony Express, The Pacific Telegraph.

|