| Photos From Wyoming Tales and Trails This page: Moorcroft, Stocks Millar, Bank Failures, Albert Charles Grandbouche. |

|

| Photos From Wyoming Tales and Trails This page: Moorcroft, Stocks Millar, Bank Failures, Albert Charles Grandbouche. |

|

|

|

|

About This Site |

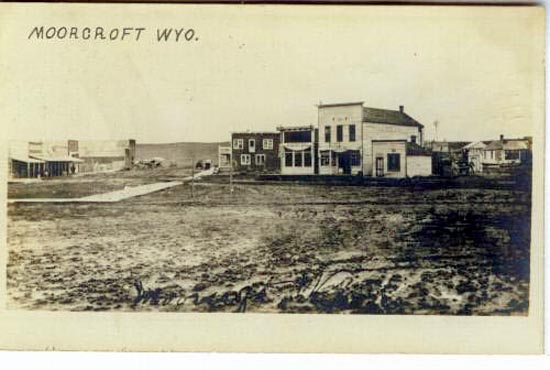

Moorcroft, 1909 Some 31 miles west of Sundance lies the small town of Moorcroft, population 807. In 1876, Alexander Moorcroft, after whom Moorcroft is probably named, became one of the first settlers of the Black Hills area of Wyoming when he settled on Sand Creek near present day Beulah. Local lore has three other versions of the naming of Moorcroft: (a) that the town was named by the first postmaster, Stocks Millar (1858-1890), after a town in Scotland, (b) it was named after an 1890's visitor to the area who liked to hunt, and (c), a variation on the first, it was named by horse ranchers named Miller after their estate in England.

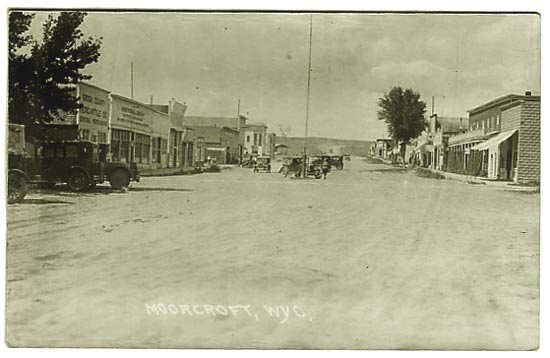

Moorcroft, 1920's With regard to the first and third explanations, an exhaustive search has been made to locate a Moorcroft in the U.K. Only three places (other than roads, streets, schools, and a sports centre), named "Moorcroft" were found, one a lunatic asylum that existed in the 1840's at Uxbridge in Middlesex, a colliery that existed in the late 1800's in Wednesbury in the West Midlands, and a pottery. The colliery is a possiblity in light of the naming of Cambria and Newcastle. Towns along the railroad were most often named by the railroad itself, usually with a pattern. Thus, the naming of the town after a coal mining area would be consistent with the naming of Cambria and Newcastle.

Moorcroft School, 1912. As to the naming of the town after an estate, the search as turned up only one estate named "Moorcroft" -- in South Australia. But, as to Postmaster Millar, like all local lore there is a grain of truth. Stocks Millar was born in in Logie, Fife, Scotland. His mother's maiden name was Sarah Moorhouse Stocks. Thus, it may be speculated that the name was derived from a combination of Moorhouse and Croft (meaning little farm). . Postmaster, Stocks Millar, died of pneumonia, after spending too much time working in the water of an irrigation ditch. As to the visitor in the 1890's, the post office bore the name Moorcroft in 1889. Thus, in the final analysis, there is no definitive answer as to how Moorcroft got its name.

Moorcroft, undated. The railroad reached Moorcroft in 1891 and the town rapidly became the largest shipping point on the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy. The town was on the Texas Trail and at its height in 1894 some 32 herds passed through going from Texas to Montana. Each herd had from 2,000 to 3,000 head. By the early 1900's the town had 3 general stores and 5 saloons.

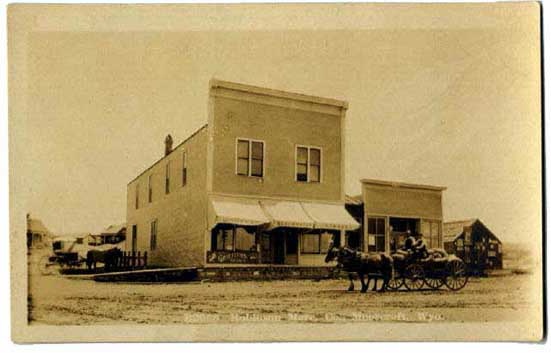

Moorcroft, 1911. The taller building is the Moorcroft Bank established in 1906 by Lucien H. Robinson, (1869-1956), John W. Rogers, and W. J. McCrea. Each were also officers of the Robinson Mercantile Company. By 1920, Moorcroft had two banks, the Moorcroft Bank and the People's Bank of Moorcroft.

Robinson Mercantile Co., c 1910. With the coming of the railroad, Robinson opened the Mercantile in a tent. It finally closed its doors in 1947. During World War I the federal government provided price supports for agricultural producds. Following the war, demand for beef declined with the result the prices dropped from over $12.00 a hundredweight to less than $7.50 per hundredweight in 1921. The price decline was ruinous to stockgrowers. A major borrower from the Moorcroft Bank was William G. Oelkers who owed the Bank some $27,800 secured by mortgages on real estate and a junior lien on cattle. In 1921, the Bank had to take over the cattle and, thus, had the expense of wintering the cattle until they could be marketed. At the same time, the Bank had to take over bands of sheep from Noah Williams and Albert Andrews. Prices continued to decline over the winter of 1921-22. The bank lost not only the loans but the cost of wintering the livestock. The bank failed. Nor were things any better for the People's Bank. It, like the Moorcroft Bank, had difficulties. In August 1921, It became necessary for the shareholders to recapitalize the bank. Not withstanding the infusion of new money, the bank failed to prosper. In September the bank was back in trouble and again in need of capital. In short, the bank required a white knight. Before 1910, there had appeared in Northeast Wyoming an individual named Albert C. Grandbouche (1889-1979). Grandbouche would later prove to be a con man extraordinaire. He had the amazing talent of getting persons to give him money in exchange for illusory but tempting promises. In 1920, he had already separated W. P. Ricketts and J. F. Waisner of the Royal Cattle Company from $20,529.86. All they had to show for the money was a judgment againt Grandbouche. Thirty-Seven years later, their heirs were still attempting to collect the judgment. Grandbouche was a director of the Citizens' Bank of Upton and developed with a plan for resuscitating the People's Bank. Grandbouche must have had a golden tongue. Major shareholders, including the President of the People's Bank, were convinced to surrender their stock with Grandbouche taking over effective control of the Bank. On October 15, 1921, the Bank was reorganized a second time with Grandbouche paying for the bank stock $17,000.00: $5,000.00 by checks drawn on the Citizen's Bank of Upton of which Grandbouche was a director and $12,000.00 in the form of a promisory note. Apparently unknown to the bank's former shareholders, the checks were rubber. Grandbouche was already overdrawn at the Citizens' Bank by $176.25. The Citizens' Bank, itself had within it only $537.18 and was overdrawn at a correspondent bank in Cheyenne. Grandbouche's apparently plan was to lift himself up by his own bootstraps and make the $5,000.00 good by borrowing the money from his newly acquired People's Bank. The State Bank Examiner discovered the scheme and both the Citizens' and People's Banks were closed.

Moorcroft Hotel, approx. 1910 All across the state, the story was the same, banks falling like rows of dominoes. As Professor Larson has noted, Wyoming had 153 banks in January, 1920. By the end of 1924, some sixty-eight banks had failed. By the end of the decade over half of the banks in the state had failed. See Larson, History of Wyoming, 2nd ed. revised p. 413. As observed by Professor Larson, depositors lost their savings and some bankers committed suicide. Grandbouche was convicted of willful misapplication of bank funds and sentenced to the State Penitentiary in Rawlins. Recidivism amongst convicts is high. In 1933, Grandbouche appeared in Denver. There he conducted a Ponzi scheme under which victims were induced to invest funds in several companies, "Collateral Bankers, Inc.," "American Industrial Loan Company," "Ameican Fidelity," and "Bush & Company," under the promise of seven percent guaranteed returns. To stave off investors checks were kited between the different companies. Although in Wyoming, Grandbouche may have cheated the comparatively affluent, in Colorado, he was no respecter of age or modest circumstances. In one instance, he cheated an eighty-year old maiden lady of her life savings which she had earned as a housekeeper and cook. Again, he was convicted of conspiracy to commit false pretenses, confidence games, cheating and swindling and sentenced to six to ten years in the state penitentiary. By the 1940's, Grandbouche had changed his name to "Al Grandbush" and was in Walsenburg, Colorado. There he operated as a stock broker under the name of "Interstate Livestock Company." Among those who ran into a financial debacle dealing with Grandbuouche was a Texas stockman named Eagle who entered into a joint venture with Grandbouche. Eagle borrowed money and entrusted it and cattle to Grandbouche. Grandbouche duly reported to Eagle that the joint venture was making money. The Internal Revenue Service required that taxes be paid on the paper income. To add insult to injury, when Grandbouche failed to pay Eagle for his share of the profits and Grandbouche's share of the expenses, the Tax Court disallowed the deduction for bad debt because: [T]he evidence consisting of testimony of Grandbush that he did not know whether he was bankrupt or insolvent, but that Eagle was unable to collect the debt in 1949 or since then, which Eagle also testified to, is insufficeint to establish the worthlessness of this obligation * * * for the mere statement that one was unable to collect a debt, in the absence of further evidentiary facts establishing this conclusion, is an inadequate basis to substantiate the claim of worthlessness. Eagle v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 242 F. 2d 635 (5th Cir. 1957) In the late 1950's Grandbouche was in Arkansas managing to convince persons to invest in oil leases. Again, he left a trail of unsatisfied judgments.

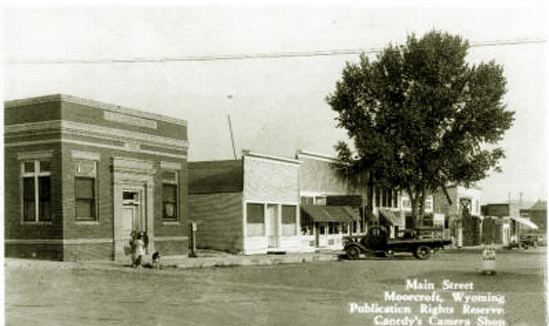

Moorcroft, approx. 1928 For the trail of lawsuits and judgments, see State v. Grandbouche, 32 Wyo. 88 (1924); Stewart v. Allison, 36 Wyo. 202 (1927); Thach v. Durham, 120 Colo. 253 (1949); Hume v. Ricketts, 69 Wyo. 222 (1952); Grandbush v. Womack , 129 Colo. 26 (1954); Eagle v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 25 Tax Court 169 (1955); Womack v. Grandbush, 134 Colo. 1 (1956); Grandbouche v. Waisner, 136 Colo. 374 (1957); Eagle v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 242 F. 2d 635 (5th Cir. 1957); Monsanto v. Grandbush, 162 F. Supp. 797 (W.D. Ark. 1958); McMillan v. Powell, 235 Ark. 934 (1962).

Moorcroft, approx. 1939 Next Page: Upton |