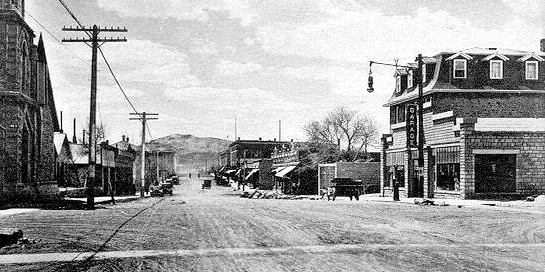

Lincoln Highway, Rawlins

To the

west of Sinclair, the early intrepid travelers came to Rawlins and the only decent

accomodations between Evanston and Laramie.

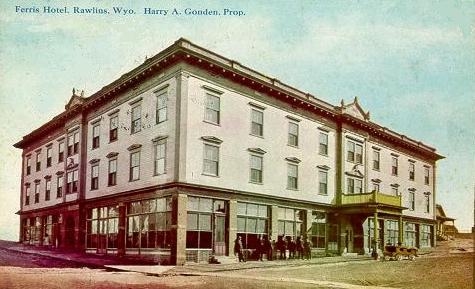

Ferris Hotel, Rawlins, 1910

Note crosswalks. Similar crosswalks will be observed in

early photos of other towns with dirt streets. The

Ferris Hotel was constructed by George Ferris. For further discussion of

Ferris and more photos of the Hotel, see Rawlins.

Oregon Trail, Sweetwater County, 1905.

As is observed with regards to the discussion of Laramie, the Lincoln

Highway did not come into real existence until after World War I. Indeed, until the 1930's, the highway was

an "improved" road only in a broad sense of the word. The highway was finally gravelled

in 1924 with the assistance of a grant from Willys-Overland.

An early visitor to

Rawlins was Harriet White Fisher, the first woman motorist to circle the globe.

She described in her memoir A Woman's World-Tour in a Motor her 1909 passage

through Carbon County in her forty horsepower Locomobile roadster:

We passed on through Point of Rocks, and near Bitter Creek had a very disagreeable time,

having to fill in washouts in the road with sagebrush, every few miles.

We crept carefully along through the soft mud, with not a vestige of life

in sight---only miles of desert meeting our view. This place, I believe,

is known as "The Red Desert."

From Bitter Creek we went on to Rawlins. Here we got off the road, and went

around the country about twenty miles to get to Hanna. The road was sandy,

with high centres, and the ground squirrels had burrowed into the ground,

making it dangerous travelling for motorists. Every now and then we would

find ourselves taking a sudden jump as the rear wheels would be buried in

these holes.

From Hanna, after a great deal of hard pulling, we managed to reach Medicine

Bow. All this time we were obliged to keep our chains on.

Writer's note: The chains were not for snow. It was July. In Medicine Bow the

intrepid travelers found no room at the hotel and were required to stay in a

boarding house where the proprietor was drunk and the travelers were awakened

in the middle of the night by the

sounds of the owner attempting to murder his wife. In

contrast, however, as indicated in the photo below, Rawlins had decent accommodations

in the form of the Hotel Ferris, photo above.

Wamsutter, 1920's.

Thirty-eight miles to the west of Rawlins is Wamsutter and the beginnings of the Red

Desert. On the Lincoln Highway, the stretch west of Wamsutter was bad. Road conditions were bad, the

scenery was bad, and services were few and far between. The area was replete with gullies and washes.

In 1907, the Routt County Development Company in its promotion of Carey Act lands in Northern

Colorado opened an automobile stage line southward from Baggs. The road was improved by cutting the sage

brush and putting wooden stringers down the sides of the worst gullys, but of a width that they would

not be used by freight wagons. On the early route of the proposed Lincoln Highway, the worst of the

washes was Marston Wash some thirty feet deep and fifty-five feet wide. Although it was said it couldn't be done,

early tourist Hugo Alois Taussig's chauffeur-driven sixty-horsepower Thomas was able to negotiate

the gully. Tassig in his privately published 1910 Retracing the Pioneers From West to East in

an Automobile, attributed the feat to the superior power of the Thomas. Allegedly, some wealthier tourists in the early years would sometimes

load their automobiles on railroad cars at Wamsutter and ship them to Rock Springs so as to avoid

the highway.

Gypsy Rose Lee in her

1957 Gypsy: A Memoir noted that she and her mother travelling to Seattle went off

the road and landed in a ditch near Wamsutter. It was winter and in the night-time. In the cold and snow as they

attempted to extricate the vehicle from the sand and snow, the sound of the coyotes howling in the

distance and coming closer and closer added to the scene. A steering knuckle on the vehicle was broken.

Gypsy and her mother spent the night at the garage since they could not afford the hotel. In the morning

with the vehicle repaired, Gypsy's mother stiffed the mechanic giving him a six dollar used watch for his efforts,

telling him it was a family heirloom which she would send for when she reached Seattle.

Writers for the Works Progress Administration had to find

something about Wamsutter. Thus, they wrote about the sky and the sheep:

* * * WAMSUTTER * * * (6,700 alt., 50 pop.),

one of the oldest wool-shipping centers in the State. Derricks top

wooden buildings over the wells, from which the

town obtains its water. On summer nights, this

lonely place is merely a small group of lights set in blackness and silence.

Over the immense darkness, stars shine brilliantly, neither dimmed by others lights nor

hidden by smoke and dust in the air. A meteor flames against

the winking stars; an aeroplane, winging toward

Cheyenne or

Salt Lake city, seems trying to imitate it. Wamsutter is on the

end of the RED DESERT, where

colors change hourly, according to the brilliance and direction of the

sunlight. Although the region seems barren,

hundreds of thousands of sheep winter there. Wyoming: A Guide to its History and

People, Works Progress Administration, 1941.

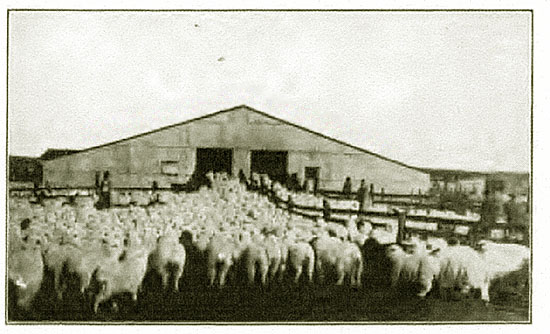

The area between Wamsutter and Bitter Creek was, indeed, a center for the sheep industry.

Sheep Shed, Bitter Creek, Wyoming, 1916.

(Writer's note: for some unknown reason, the scene reminds me of an airport security area.)

Wamsutter was originally named

Washakie but was renamed to preclude confusion with Fort Washakie. Near Wamsutter

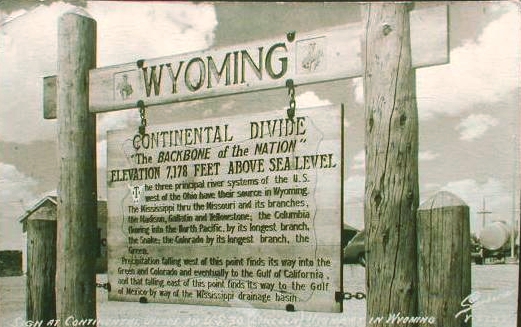

travelers cross the Continental Divide on one side of which all water flows to

the Pacific and on the other to the Atlantic.

Continental Divide near Wamsutter

In actuality, it takes almost sixty miles to cross the Continental Divide. Just to

the west of Rawlins one enters the Great Divide Basin from which no water (what there is of it) flows. One

does not leave the Basin until just before Table Rock. Near Wamsutter there was erected a monument

to Henry Joy, promotor of the Lincoln Highway.

Henry Joy Monument at Continental Divide near Wamsutter

The Monument has now been moved to Sherman Hill hear the bust of Abraham Lincoln.

Ms. Fisher was not the only one to complain of the condition of the roads through the

Red Desert. Over thirty years before John H. Beadle (1840-1897) passed through the area. In his

1873 book, The Undeveloped West; or Five Years in the Territories,

he described the Bitter Creek area:

At daybreak we rose, stiff with cold, to catch the only temperate hour

there was for driving; but by nine A.M. the heat was most exhausting.

The road was worked up into a bed of blinding white dust by the laborers

on the railroad grade, and a gray mist of ash and earthy powder hung over

the valley, which obscured the sun but did not lessen its heat. At

intervals the 'Twenty-mile Desert,' the 'Red-sand Desert' and the

'White Desert' crossed our way, presenting beds of sand and soda, through

which the half-choked men and animals toiled and struggled, in a dry air

and under a scorching sun. In vain the yells and curses of the teamsters doubled and redoubled,

blasphemies that one might expect to inspire a mule with diabolical

strength; in vain the fearful 'blacksnake' curled and popped over the

animals' backs, sometimes gashing the skin, and sometimes raising welts

the size of one's finger. For a few rods they would struggle on, dragging

the heavy load through the clogging banks, and then stop, exhausted,

sinking to their knees in the hot and ashy heaps. Then two of us would

unite our teams and, with the help of all the rest, drag through to the next

solid piece of ground, where for a few hundred yards the wind had removed

the loose sand and soda and left bare the flinty and gravelly subsoil.

Thus, by most exhausting labor, we accomplished ten or twelve miles a day.

Half an hour or more of temperate coolness then gave us respite till soon

after sundown, when the cold wind came down, as if in heavy volume, from

the Snowy Range, and tropic heat was succeeded by arctic cold with amazing

suddenness. On the 27th of August one of my mules fell twice, exhausted

from the heat; that night ice formed in our buckets as thick as a pane of

glass.

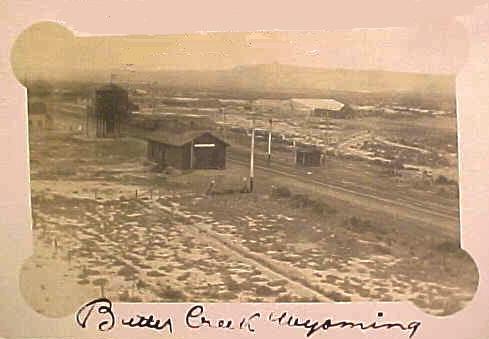

Bitter Creek, 1913

Bitter Creek held memories for George Wyman. He later wrote in

Motorcycle Magazine:

Bitter Creek might well be called Bitter Disappointment. I do not mean the

stream of water that the road follows, but the station of the same name. It

is one of those places which well illustrates what I have said about the

folly of taking the map as a guide in this country. About one-third of the

"places" on the map are mere groups of section houses, while a third of the

remainder are just sidetracking places, with the switch that the train

hands shift themselves, and a signboard. Bitter Creek belongs to the former

class. The "hotel" there is an old boxcar. Yet, if you take a standard

atlas you will find the name of Bitter Creek printed in big letters among

a lot of other "places" in smaller type. The big type, which leads you to

think it must be quite a place, means only that the railroad stops there.

The "places" in smaller type are mere sidetracking points. The boxcar is

fitted-up as a restaurant and reminds one faintly of the all-night hasheries

on wheels that are found in the streets of big cities. The boxcar restaurant

at Bitter Creek, however, has none of the gaudiness of the coffee wagons.

Still, I got a very good meal there. When I cast about for a place to

sleep It was different, but I finally found a bed in a section house.

This experience was one of the inevitable ones of transcontinental touring.

It was 7:15 o'clock when I reached Bitter Creek Station and it is 69 miles

from there to Rawlins, the first place where I could have obtained good

accommodations.

Today, the "town" of Bitter Creek is some 8 miles south of I-80 at exit 142.

Eighteen years later in 1921 two Canadian tourists, Charles and Doretta Beach,

undertook a 10,850 mile odyssey in a brand-new Nash automobile which they picked up

at the factory in Kenosha, Wisc., proceeding across the United States, up to British Columbia,

down to Mexico, onward to Texas, and back to Ontario. In her

diary, Mrs. Beach complained that the stretch from Wamsutter to Rock Springs was the

worst of the whole trip. She noted that it took the better part of a day to go

the 115 miles from Rawlins to Rock Springs, and the first 40 miles of that was on a

fine road.

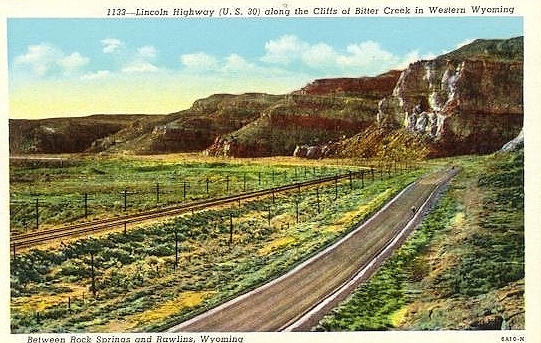

Lincoln Highway, 1930's, along Bitter Creek

The creek, however, provides fine vistas as indicated by the next postcard.

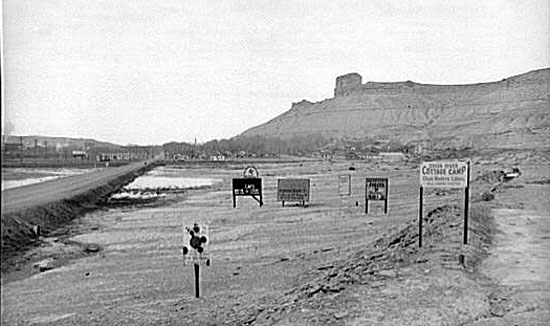

Further on to the west lie Rock Springs and Green River.

Entrance to Green River, U.S. Highway 30, looking west, 1940.

Next page: Lincoln Highway, Green River Palisades.

|