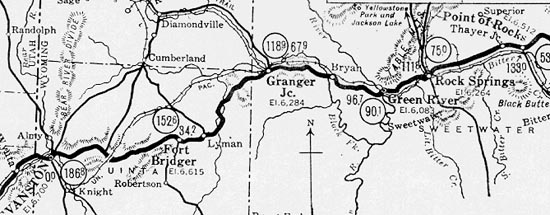

Lincoln Highway Map, Point of Rocks to Evanston

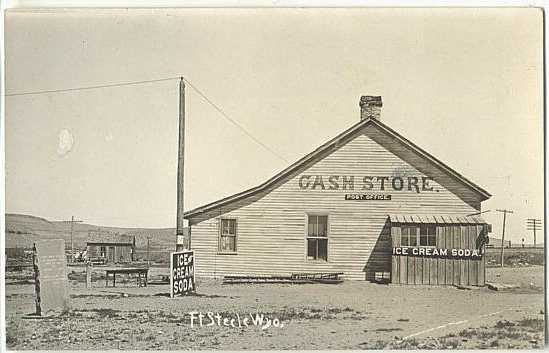

Fort Steele Post Office, approx. 1920.

Some 43 miles west of Medicine Bow on the Lincoln Highway, bypassing Hanna and Elk Mountain,

is the abandoned military post of Fort Fred Steele. The monument in the left of the above photo

recites:

FORT FRED STEELE

U.S. MILITARY POST

JUNE 30, 1868

TO

AUGUST 7, 1886

MARKED BY THE

STATE OF WYOMING

1914

Sager's Servce Station, Fort Steele, 1920's

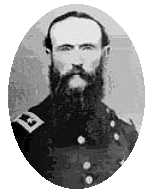

Frederick Steele

The Fort, named after Civil War Brevet

Major General Frederick Steele by Richard Dodge, was one of the three

great forts established to protect the Union Pacific and its workers from marauding Indians. The

other two forts were Forts D. A. Russell and Sanders. OUtside of those forts cities arose. D. A. Russell gave rise to

Cheyenne and Fort Sanders to Laramie.

Frederick Steele

The Fort, named after Civil War Brevet

Major General Frederick Steele by Richard Dodge, was one of the three

great forts established to protect the Union Pacific and its workers from marauding Indians. The

other two forts were Forts D. A. Russell and Sanders. OUtside of those forts cities arose. D. A. Russell gave rise to

Cheyenne and Fort Sanders to Laramie.

General Steele had served in the Mexican War. During the Civil War, Steele

fought without much distinction against CSA Gen. Edmund Kirby-Smith in Arkansas and Texas.

Notwithstanding a personal appeal delivered by his

brother, a Democratic congressman from New York, to President Lincoln,

Steele was ultimately removed from Command. Lincoln did not even respond to the

entreaty by Congressman Steele.

Following the war Gen. Steele was reduced to his permanent rank of Colonel and in 1868 died in

San Mateo, California.

Fort Fred Steel was isolated and desolate. No nearby city arose. At first speculators started to set up a town on

the east bank of the North Platte opposite the Fort. The new town to be known as "Brownsville" was quickly squelched by vigilantes known as the

"Gunny Sack Brigade," and by the

Fort's Commanding Officer, Richard I Dodge, who forbade any settlements within three miles of the fort. In Cheyenne, the

Gunny Sack Gang conducted within one six-month period some twenty extra-legal hangings. Thus, as one post

surgeon noted in his 1870 report, "There are no inhabitants in the vicinity unconnected with

the railroad or post." Indeed, he continued, there were very few Indians. The fort's location was dictated by the necessity of

protecting the railroad bridge where it crossed the North Platte. The fort was constructed on a bluff overlooking a bend in the

river with the aptly named Rattlesnake Hills and Rattlesnake Butte serving as a backdrop. The soil and climate was such

that the usual vegetabe gardens for most forts could not be grown. To supplement the menu, the men had to purchase vegetables from the

post trader. The area was swept by continual winds. The post surgeon noted in his report,

"Artificial policing of camp is rendered almost superfluous, as the violent west winds,

which frequently prevail, sweep almost everything loose off the bluff.

From the nature of the climate, putrefaction is almost impossible."

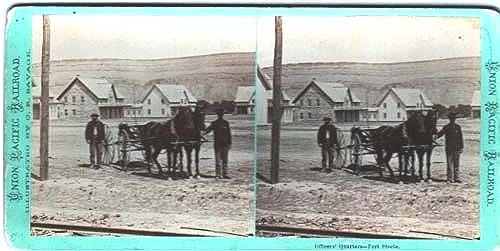

Officers' Quarters, Ft. Fred Steele, approx. 1870, stereograph by C. R. Savage

Originally, it was intended to build the fort's buildings of stone. That quickly changed with only the commanding officer's

quarters being construct of stone. The remaining buildings were constructed to standard army plans of timbers brought in from Elk Mountain and

cut in one of two steam-powered saw mills brought in by the army.

Officers' Quarters, Ft. Fred Steele, approx. 1870.

Enlisted men's barracks consisted on one-story buildings each able to house one hundred men, to conserve heat two men to a bunk. The officers'

quarters had lath and plaster. The enlisted men's barracks were lined with tar paper. The 1870 surgeons'

report noted that there were no special arrangements for bathing. Water from wells was undrinkable due to alkali. Water was collected in cisterns until

the army brought in pumps to get water out of the river. Even though the river was swifty running, in the winter it would freeze almost solid.

With lack of rain, in the summer, the river would take on a milky hue and, according to the surgeons, "bowel affections" became prevalent.

Ft. Fred Steele railroad depot, approx. 1880's.

With no saloons, hog ranches, or Indians to fight, there was little to relieve endless boredom at the fort

except for the nightly excursions by wolves at the edge of the fort and the repeated trips to the

latrine in the summer as a result of drinking the water. The only military engagement of consequence from the

fort was the Battle of Milk Creek 155 miles to the south in Colorado where the fort's commander was ambushed by

Utes. The massacre made Joe Rankin famous with his epic

165 mile ride back to the fort in 28 1/2 hours, changing horses only twice, to deliver word of the

massacre of Thornburgh and his Company.

The fort was abandoned by the military in 1886. Bodies in the cemetery were removed to Fort McPherson, Nebraska. The body of

Major Thornburgh was recovered following the massacre and buried in Omaha and later removed to Arlington National

Cemetery. The bodies of those killed with him buried in unmarked shallow trenches near where they fell, 20 miles north of Meedker Colorado, on what is now

sheep pasturage. Their remains were discovered in 2000 but the owners of the property proved to be uncooperative in allowing

the troopers to be removed for a military burial in a national cemetery.

Enlisted Men's Quarters, Ft. Fred Steele, undated.

Eight years after abandonment, the fort and its buildings were purchased by the

Cosgriff Brothers and became a center of the wool industry. In 1895, the

Cosgriff Brothers shipped out a trainload of 800,000 lbs. of wool. Additionally, a

sawmill was operated, taking advantage of the ability to float logs down the

North Platte from the Medicine Bows.

Sawmill, Fort Steele, undated.

Shortly thereafter, most of the town burned down, with the remainng buildings being

acquired by the Leo Sheep Company.

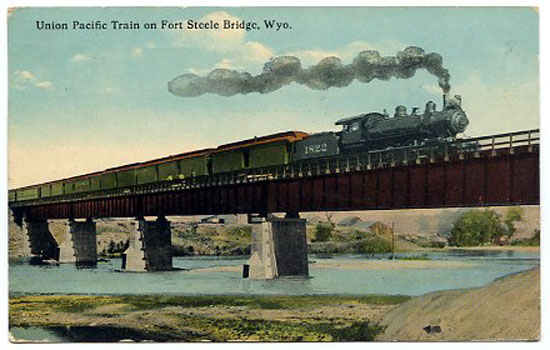

Fort Steele railroad bridge, approx. 1910

.

With the establishment of the Lincoln Highway in the area in 1922, the town had a

brief economic resurgence which ended with the relocation of the highway in 1939. Today the

area has been designated as a state historic site with little more remaining but the

foundations of the buildings.

Ft. Fred Steele, 2003, photo by Geoff Dobson

The dark, box-like objects in the ruins are stoves. Few of the original buildings today survive, most victims of fire. Indeed,

even when the fort was in use, several buildings were lost due to fires started by sparks from the

passing locomotives.

Fort Steele School, 2003, photo by Geoff Dobson

When Alice Ramsey passed through Ft. Steele, the bridge was out and she was obliged

to bump along over the railroad bridge. There was another difficulty with the

roads in the area:

"Across Wyoming the roads threaded through privately owned cattle ranches.

My companions [Hettie Powell, Margaret Atwood, and Hermine Jans] were obliged

to take turns opening and closing the gates

of the fences which surrounded them as we drove through. If we got lost

we'd take to the high ground and search the horizon for the nearest

telephone poles with the most wires. It was a sure way of locating the

transcontinental railroad which we new would lead us back to civilization."

Lincoln Highway continued on next page.

|