|

Lincoln Way and the

Plains Hotel, Cheyenne, 1929

In the early years of the Lincoln Highway, after leaving Omaha, the first place one was likely to

come across paved streets was Cheyenne. For photos and history of Wyoming's capital city, see

Cheyenne . In Cheyenne the highway proceeded down 16th Street, Lincoln Way.

The red brick building (at the right in the photo) across the street from the Plains Hotel is now the location

of the Grier Furniture Company. At the time of the photo, it housed Hobbs, Huckfeldt and Finkbiner (later Hobbs and Finkbiner)

furniture and funeral directors. The practice of combining furniture sales and undertaking in

Wyoming was not all that unusual. For a discussion of the subject see

Lusk.

The hotel, now known

as the "Historic Plains Hotel", was designed by William R. Dubois. For discussion of Wm. R. Dubois, see

Cheyenne III. The Plains Hotel has served as a meeting place since its construction and served

as the founding location for the Union Pacific Employees Clubs which started in Cheyenne and now has

branches throughout the system. The Hotel is allegedly haunted

by the ghost of an individual pushed from a fourth floor window.

Clustered within within walking distance of the Union Pacifc and Burlington Railroad stations there were a number of hotels. These included

besides the Plains Hotel, the Albany, the Becker, the Normandie, the Wyoming, the Strand and the Metropolitan.

With the coming of the Lincoln Highway and the loss of

railway passenger service all but the Plains have disappeared.

Although in 1911 the Legislature provided for the establishment of a system of public highways and the

Lincoln Highway was officially established in 1913, no real action was taken

to improve the roads until 1919. The Highway Department was created in 1917, but the War delayed any real

action unil after the war. The Lincoln Highway was initially a collection of short ill locally-maintained dirt and gravel roads. The 1916 Complete Official Guide to the Lincoln

Highway noted that by 1912 less than a dozen transcontinental trips by motorcars had actually completed the trip "under the car's own power." p. 13 By the time of the

1916 Guide the intrepid tourist was assured, assuming decent weather, as "one speeds over the Lincoln Highway in his modern automobie" the journey could be

completed from coast to coast in twenty days with nothing but an enjoyment from one end to the other." Guide, p. 10.

The qualifier was the assumption of decent weather. If one met rain, the mud caused much

delay while one waited for the mud to dry out. In 1915, Emily Post drove across the continent.

Outside of Chicago she met the much. She wrote:

Thirty-six miles out of Chicago we met the Lincoln Highway and from the first found it a disappointment. As the most important,

advertised and lauded road in our country, its first appearance was not

engaging. If it were called the cross continent trail you would expect

little, and be philosophical about less, but the very word "highway"

suggests macadam at the least. And with such titles as "Transcontinental"

and "Lincoln" put before it, you dream of a wide straight road like the

Route Nationale of France, or state roads in the East, and you wake

rather unhappily to the actuality of a meandering dirt road that becomes

mud half a foot deep after a day or two of rain!

The highway itself disappeared into a wallow of mud! The center of the

road was slightly turtle-backed; the sides were of thick, black ooze and

ungaugeably deep, and the car was possessed, as though it were alive,

to pivot around and slide backward into it. We had no chains with us,

and had passed no places where we could get any. Apart from the difficulty

of keeping going on chainless tires our only danger, except that of being

bogged, was in getting over the bridges that had no railings to their

approaches. The car chased up every one, swung over toward the embankment,

slewed back on the bridge, went across that steadily, and dove into

the mud again! It certainly was dampening to one's ardor for motoring.

If the Lincoln Highway was like this what would the ordinary road be after

it branched away at Sterling

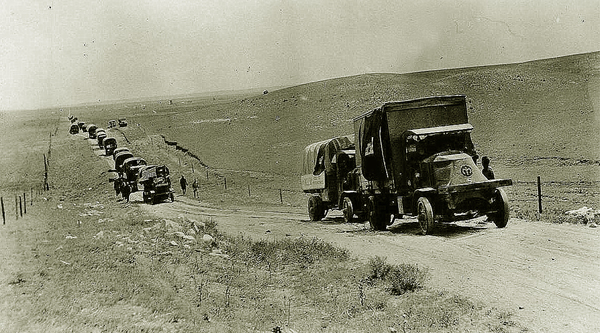

First pause of Military Convoy in Wyoming, August 8, 1919.

Following the War, in 1919 the War Department tested the feasibility of using covoys of trucks to transport

supplies across the continent following the Lincoln Highway. A convoy of 81 military vehicles was to domonstrate the feasibility

of using trucks to carry equipment. Secondary sources as to the numbers of vehicles in the convoy have been found.

It may be speculated that the

different numbers relate to numbers given for motorized vehicles, counting only vehicles that completed

the expedition, or omission of two privately provided vehicles, a Packard truck

provided by Firestone loaded with spare tires, and Lincoln Highway Association Field Secretary H.C. Osterman's

red, white and blue Packard Twin Six.

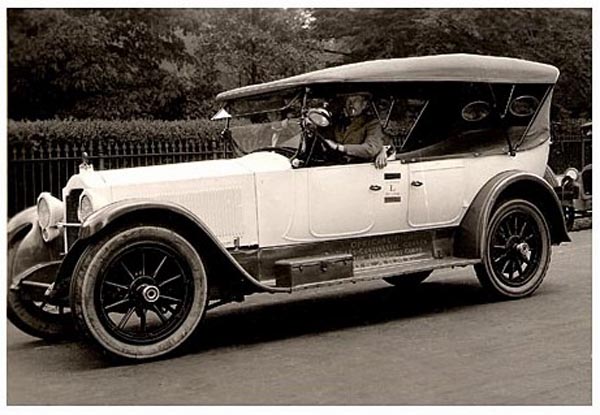

Advance Car furnished by Lincoln Highway Association,Washington, D.C.

A complete list of military vehicles is included in a report by 1st Lt. E. R. Jackson of the

Army Ordinance Department is on file in the Eisenhower Museum in Abilene, Kan. The trip demonstrated that the

highway was not yet ready for prime time. The trip was a nightmare. In Wyoming alone, fourteen bridges could not support

the weight of the heavy trucks. But then many of the bridges were somewhat weak in appearance.

Packard Truck furnished by Firestone crossing bridge somewhere west of Laramie.

On August 8, 1919, the convoy

crossed into Wyoming from Nebraska.It was met by Governor Robert Carey at Hillsdale. It took

only 11 hours to go the 66 miles to Cheyenne. When the convoy reached Archer, word was conveyed to Cheyenne.

There, whistles from various steam laundries were blown and firebells rung to signal

the convoy's approach. East of town it was met by the 15th Cavalry Band.

The convoy proceeded up Capitol Ave. The convoy was normally led by

Expedition commander Lt. Col. Chas. W. McClure. At Frontier Park a rodeo, organized by C. B. Irwin, Chas Hirsig, Wm. Dubois, and R. B. Davidson, was presented to the

members of the convoy. A thunder storm had just ended as they arrived at the Park and a double rainbow greeted

the convoy as it pulled up to the arena.

World Champion cowboys Eddie McCarty and Floyd Irwin participated. C. B. Irwin acted as master of ceremonies.

A rumor had circulated amongst the troops that Col. McClure's seven-passenger Cadilac and gone off the road several days before and had

gotten stuck. When Irwin announced a demonstration of bronco busting, he told the audience to laughter that Col. McClure himself would give a

demonstration on a bronc named "Cadilac."

Military Convoy eastern Wyoming, August 8, 1919.

On August 9 the convoy left Ft. D.A. Russell at 7:45 a.m. Lunched on Sherman Hill and crossed the Continental Divide at 2:00 p.m. Four miles east of

the divide one of the Mack trucks broke through a small bridge. The convoy proceeded to

Laramie by way of Telephone Canyon. Originally the Lincoln Highway went by way of Tie Siding but in 1916 the route was relocated.In 1930 a plaque was placed indicated the naming of the canyon.

The repairs to the bridge delayed the convoy by twenty-seven minutes.

In Laramie the convoy proceeded straight to the Fair Grounds. A dance was given at the Woodmen of the World hall for members of the

convoy. The sixty-seven miles from Cheyenne took

11 1/2 hours. The next day was a Sunday and an official "day of rest." the day was spent servicing

the vehicles. In the afternoon there was a

rain and wind storm.

Military Convoy Rock River, Wyoming, August 11, 1919.

Military Convoy Rock River, Wyoming, August 11, 1919.

On August 11, the convoy departed Laramie for Medicine Bow at 6:30 a.m. Twelve bridges had to be reinforced with lumber provided by the

State Highway Department. Dust caused some carburetor troubles. In Medicine Bow the citizens served barbecue at the

Virginian Hotel followed by a street dance. The 59 miles from Laramie took 11 1/2 hours.

August 12. departed Medicine Bow at 6:45 a.m.. West of Medicine Bow it became necessary to lay down

a "portable corduroy road." The road was located on a abandoned railroad right of way. As a result, the road was only a single lane.

Where the railroad ties had been removed leaving indentations in the roadbed. This would

cause vehicles to skew sideways toward the ditch on the side.

A "B" truck whose right rear wheel skewed into an adjacent ditch.

They stopped at Fort Steele.

They ran into a 40 m.p.h gale. Twelve bridges had to be

reinforced and two entirely rebuilt. It took 12 1/2 hours to go the 62 miles.

August 13. The next day the convoy set out for Tipton Station at 6:30 a.m. If anything conditions

cited in the convoy's log appeared worse.

Numerous mechanical problems were noted. Bridges had to be reinforced. The tanker

slipped off the road and rolled over 270 degrees. It was righted by two other trucks and was on its way in 20 minutes.

It took 10 3/4 hours to go the 58 miles to Tipton

Station. The keeper of the Log noted: "Camped on Red Desert, on barren sandy plain, no

inhabitants or buildings other han railroad pesonnel and property. Nearest natueal water supply is 16 miles."

August 14: one of the Dodge Brothers staff cars had to be towed to Rock Springs. A separate log maintained by the

Ordinance Department reflected one or more of the class "B" trucks had to be towed almost daily. It took

13 1/2 hours to go to the 76 miles of the day's trip. Night was spent at Green River.

Off-loading tractor from Mack Class "B" truck whose Right rear wheel had broken through bridge

decking near Granger, Wyoming, August 15, 1919.

On the morning of August 15, about two miles west of Granger Junction the right rear wheel of a Mack truck carrying a tractor broke through a bridge.

After the tractor was off-loaded. It pulled

the Mack out. The rest of the covoy was detoured through the creek bottom. Near Lyman both rear wheels of the same

Mack broke through the planking of the bridge over the Black Fork. That day it took 17 hours to go 63 miles. The White staff car broke an axle and

had to be towed to the next camp. Numerous problems with other bridges.

Examining bridge for structural sufficiency.

Near Lyman,

the convoy had to use other dry creek beds in lieu of the highway.They spent the night at an abandoned

army post at Ft. Bridger.

The next day, August 16, it took 7 1/2 hours to go the 36 miles to Evanston. The Militor towed

the Class B machine shop truck which required a new cylinder block,

piston, connecting rod and bearings.

The next day in Utah was worse. The Militor had to tow four different Class B trucks. The Militar, officially a "Military Artillery Wheeled Tractor,"

was a huge four-wheel drive vehicle especially designed

to tow 155 millimeter howitzers. It was equipped with an 8-ton wench and

shovel. In early tests, the vehicle could match anything done by a

Holt tractor but, in addition unlike the Holts, it could travel at highway speeds. In the convoy, it was the one of the few vehicles except

the Packards that did not have to be towed.

Even the motorcycles used by advance scouts broke down.

At the time, the Army had only six of the Militors. The vehicles

cost $8,000 each (Equal to approximately $120,000 as of 2018). The Army apparently loved the vehicle,

but with the war being over, the Quarter Master General and Congress didn't.

The Army was accused of participating in an "orgy of money spending."

See New York Herald, December 15, 1920, p. 9. A contract for

the purchase of a large number was cancelled. As a result, the Militor Corporation was reorgzanized twice and went into

bankruptcy in 1921.

A Militor, 1918.

The demonstration was significant. Thirty-three years later a young

Brevet lt. colonel accompanying the covoy as an observer, D. D. Eisenhower, was elected President.

He remembered the adventure and pushed for the adoption of the Interstate Highway Sysem. Eisenhower reported at the end of the trip:

The Militor, equipped with power winch and spade in rear, did wonderful work in pulling vehicles out of holes,

sand pits, etc. The 5-ton tractor was also very efficiently used

for this purpose. On one occasion at least, the Militor came into camp at night towing four trucks, showing that its power plant was almost perfect.

In the lighter types, very little difficulty was encountered. The only Packard trucks on the trip were three of the 1 ½ ton type. Mechanical difficulties in these were so few as to be negligible. A burned out wheel

bearing, repaired at Carson City, was caused by an error in placing same when tires had been changed at Salt Lake City. These trucks surmounted the stiffest grades with motors running quietly and easily,

and trucks in good condition. One Packard truck was badly overloaded

during the entire trip. Its load was partially distributed in latter part,

but when weighed near end of trip, its gross weight was still 1,500

pounds in excess of that of any other type of 1 ½ ton truck.

The performance of these three trucks is considered remarkable.

The White 1 ½ ton trucks were also very good, and difficulties encountered

with them were trifling. This also applies to G. M. C. type.

Among the touring and observation cars very little difficulty was

encountered. One Cadillac touring car required a timing chain, and in

the mountains carburetters needed adjusting.

One White observation car (truck chassis) had frequent difficulty of a

minor nature, due to stoppages in oil line. The same car burned out a

wheel bearing and lost a rear wheel in Wyoming, necessitating the

replacing of the whole rear end.

Kitchen trailers were of the two and four wheel type.

The only one to finish the trip was one of the two wheel type (Liberty).

The trail-mobiles, four wheel type, were constantly in trouble. Officers

of M.T.C. maintained that these troubles were the result of improper

trailer connections; proper ones not being provided. In my opinion

neither type is suitable for transport work, and a better one must

be devised.

Motorcycles had much trouble after getting in the sandy districts.

Except for scouting purposes, it is believed a small Ford roadster

would be better suited to convoy work than motorcycle and side car.

Lincoln Highway, Wyoming, 1920.

Music this page: Lincoln Highway, a Two Step composed in 1921 by Harry J. Linoln(1878-1937) and arranged for

Horse Creek Cowboy Band. It was a popular dance hall number in the 1920's.

Next page, Lincoln Highway through Cheyenne.

|