Ivinson Ave. (formerly Thornburg.) looking west from Second Street toward Union Pacific tracks on

First Street, 2005. Photo by Geoff Dobson.

Originally, the east-west streets in Laramie were lettered, i.e. "A" street, "B" street, "C" street, etc. Subsequently, they were named after

military heroes, i. e. Fremont, Garfield, Thornburg (after T. T. Thornburgh), etc. Thornburg was renamed after

Edward Ivinson.

Buckhorn Bar, Ivinson Ave., 2005. Photo by Geoff Dobson.

The Buckhorn is downstairs. The Parlor is upstairs. The Buckhorn is the type of

place where students after a victory over Colorado State or Brigham Young will dutifully bring the

goal posts. The Buck, frequented by multiple generations of Cowboys from the University of Wyoming, is famous both in fact,

fiction, and speculation. The saloon is "tastefully" decorated with dead animals on the walls including both frontal and

in one instance, a rear end view. Hanging from the ceiling is a hangman's noose. The mirror over the backbar is famous for its bullet hole. Indeed, a replica of the mirror, complete with

bullet hole, has been featured in an art show.

Bullet hole in Backbar Mirror, Buckhorn Bar, Laramie. Photo by Geoff Dobson.

The bullet hole was placed in the mirror by one Charlie Phillips in August 1971. Charlie had become smitten with Nelda, one of the

bartenderesses. Nelda, however, rejected Charlie's attentions. Having had perhaps one too many, Charlie, possibly to get

attention, whipped out his revolver and fired a shot into the ceiling. He then went out to the alley and

fired off another shot. He then went around to Ivinson Avenue and plugged a neat shot right through the "C" in the

Coors sign. Inside, the customers were all ducking for cover. The Coors shot went through the front window and hit the

backbar mirror. The mirror had been replaced only a few weeks before. Mirrors are expensive. Thus, it was not replaced.

Charlie was taken into custody. Firing a shot through a Coors sign is obviously the sign of a mental

aberration. He was, accordingly, sent off to the State Hospital in Evanston. There he again became besmitten with a young lady.

The two escaped and made their way to Albuquerque where he found employment. His employer dutifully wrote to

authorities in Laramie advising as to how well Charlie was doing. He even received a promotion in his work.

Since Charlie was now New Mexico's problem, Wyoming authorities did not send for Charlie. Nevertheless,

Charlie ultimately voluntarily returned to Laramie and did a short term in the county hooseqow.

The dents in the pay phone, allegedly bullet dents, were woven into fiction. See Jen Billman, "Inkneck," Ploughshares, the

Literary Journal at Emerson College, Fall 2005:

But the licking of a novelist at billiards wasn’t something I needed—who

but Bob and his blogger pals would it impress? The act seemed akin to

saying you beat Mark Arn, the local weatherman on Channel 5 out of Cheyenne,

or even the Governor of Wyoming, what’s-his-name?—who would care? But then,

because it’s in the darkest pockets of our already-black souls, what we did

not want to do was to get beat by a novelist, not even a ham-fisted one

like Cormac McCarthy.

So we practiced. Upstairs at the Buckhorn Bar down by the Union

Pacific switchyard in old Laramie. The Buckhorn is the closest you can get

in Wyoming to the image in our minds of El Paso, Texas; the rest of Laramie,

Wyoming, in general, are the Horse Latitudes of Culture. But in the Buck

there are bullet dents in the pay phone—not holes, but dents, where a .38

Special’s slugs tried and failed to pierce the old and reliable

communication device. No one still here knows the story of whether or not

someone was on the phone and between lead and miracle material at the time

of the denting.

The writer, himself, must confess that he has been tempted at times to shoot a pay phone

and put it out of its misery.

Allegedly also, a stale glass of beer sits on a shelf in the Buck awaiting the return of a customer

who went to the restroom some twenty-two years ago, but unfortunately had the temerity to

die in the john and, thus, has not yet reclaimed his beer. The Buckhorn has even found its way

into the annals of the Wyoming Supreme Court involving another incident with gunplay arising out of the

Buck. Thus, in Sturgis v. State, 1997 WY 10, 932 P. 2d 199, the

Court wrote of the adventures of two customers and a 70-year old bartender from the Buck:

By October 14, 1994, Sturgis was well known at the Buckhorn Bar in

Laramie. On the evening of October 11, Sturgis caused some consternation

when she produced a pistol hastening the departure of a paying customer.

Turning her attentions to a part-time bar employee in his seventies,

Sturgis suggested an assignation, threatening to kill him if he refused.

Unaware of the events which took place a few days beforehand, Bill

Broderick (Broderick) felt flattered when Sturgis asked him to join her in

a drink on October 14. Learning she was a stranger to Laramie, Broderick

offered his couch for Sturgis to sleep on, also inviting the bartender over

for a nightcap.

The bartender arrived at Broderick's home to witness Sturgis sitting

astride Broderick's lap as he reached around her to play the piano. After

the couple adjourned to the bedroom, however, the bartender observed

Sturgis making a dramatic exit, stumbling out the front door before

tumbling across the front lawn, spilling the contents of her purse.

Feeling out of place, the bartender sought to make his own quick exit

only to be stymied by a car that refused to start. Seeking reconciliation,

Broderick emerged to help gather the contents of Sturgis' purse while she

ran back into the house to retrieve her pistol. When Sturgis returned,

armed with her pistol, Broderick continued efforts to defuse the situation

until she leveled her pistol at him. Desperately trying to start his car,

the bartender shrewdly advised Broderick that the time had arrived to effect

an orderly retreat.

As Broderick wisely withdrew, however, Sturgis opened fire from about

fifteen feet behind, fracturing "the main bone of the left leg" and

blowing part of that bone out through the exit wound. Convinced his

assailant meant to finish the job, Broderick dragged himself into the house,

bolted the door, then pulled himself out the back door toward an all-night

convenience store. True to her victim's expectations, Sturgis kicked down

the front door, fired into the house, pursuing Broderick through the house

and down the alley until confronted and apprehended by officers of the

Laramie Police Department.

Undoubtedly, the Buckhorn had an impact on the writer's oldest son's grades, a fact confirmed

years later, long after the son finally graduated. Recently, the writer and son were in Laramie together.

As we made a nostalgic trip by the Buck, the son's old fraternity house, and out to

Vedauwoo, Son recalled his adventures at the Buck and

the parties at Vedauwoo. But although the writer at the time of the son's

poor grades was perhaps unhappy, there was an unexpressed understanding. The

writer recalled from years before when the writer, himself, was in school,

holding the phone in the fraternity house away from his ear as the writer's father

expressed over the phone in a rather

loud fashion parental concern over the writer's own grades.

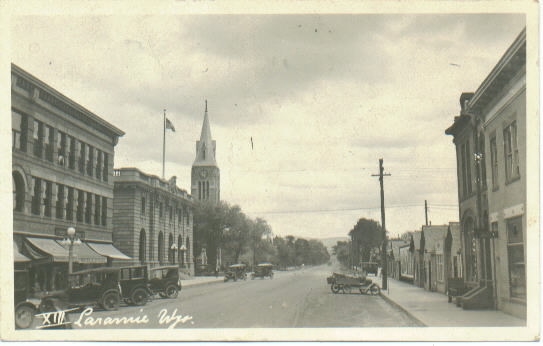

Thornburg looking east, approx. 1920, photo by Henning Svenson

The first building on the left is the Converse Building constructed by Nelson Jesse Converse (1862-1938) in 1906.

Converse had taken over management of his step-father's jewelry store by age 18. Later he was active in

the Royal Arch Masons. The post office in the above-photo,

on the corner of Ivinson and

Third Street, is now the site of the First Interstate Bank. Further down the

street is St. Matthew's Episcopal Cathedral constructed in 1896.

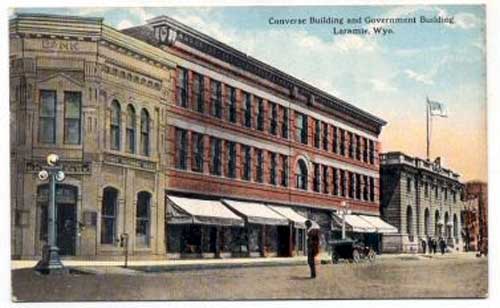

North side of Thornburg Ave. from 2nd Street. In order:

the First National Bank, the Converse Building, and the Post Office.

Since the early 1900's, there has been speculation and rumor as to the activities carried on within the second

floor of some of the buildings in the downtown area.

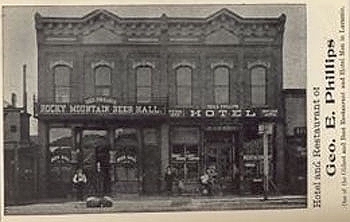

Phillips

Hotel and Restaraunt, 1901

The building was constructed by

J. F. Hesse in 1889. The upstairs was a large open hall used for dances and other similar functions. In the early

1890's, the building was sold to George Phillips who divided the structure into twenty-five separate rooms. It has been

speculated that the twenty-five rooms were used for sporting purposes.

It kind of reminds the writer of a time some thirty years ago when, in another state, the

writer with a partner owned a small office building on the edge of the respectable area of town. On the

side of the building was a street which led to a less desireable area, the kind of section where government puts its less

desirable functions such as sewage treatment plants and soup kitchens. Behind the

office building on the side street was a vacant two-story pink building looking much like Lusk's Yellow Hotel. There

was a danger that someone might establish some business such as a saloon in the pink building which would

depreciate the office building. Therefore, a decision was made to buy the pink structure. The building was

purchased without ever inspecting it. Following the closing, the writer armed with a new key opened a

door which led to a stairway. At the top of the stairs, there was another door. Beyond the door was a

large windowless central room illumniated only by light coming through the doorways of

a series of small cubicles on the sides of the big room. The cubicles had apparently been used as bed chambers.

In the absolute center of the large central room was a claw-footed bathtub, the

purpose of which the writer to this day does not fully understand. The building was razed. The writer's wife still tells

people that at one time the writer owned a pink bawdy house.

A review of the 1880 census for Laramie indicates that there were at least three such facilities on

Front Street, a white facility owned by Lizzie Palmer and two mulatto facilities. Additionally,

the census also reflected that there were three soiled doves on 3rd Street. The census is unusual in that it

clearly shows the professions of the various doves. The entry for Lizzie Palmer shows

occupation as "Keeping House of Ill Fame." Normally, in most towns the census merely reflects the

inmates of such establishments as "keeping house," "actresses," or "boarders." Thus, in the 1870 census for

Cheyenne, the famous madam Ida Hamilton is shown as a "housekeeper" and the remaining residents of

the house (excepting the cook) are shown as "dressmakers." However, the Cheyenne census for 1880

was also an exception. There,

although Ida Hamilton is shown as "keeping house," no doubt is left as to the

profession of the remaining seven female inmates of Hamilton's establishment.

It has been contended that Laramie tolerated

the existence of the facilities as a revenue raising measure by collecting fines of $7.00 and $7.50. There

were repeated arrests and fines for Sophia Riccard a resident of 3rd Street, but any belief that the

City fathers were merely using the situation to raise money is speculation. Just as likely is that

there was a difficulty in obtaining convictions or adequate fines under the territorial laws.

In 1873, Cheyenne's famous madam, Ida Hamilton, as an example, was prosecuted in the District Court for

Laramie County and found guilty of "keeping and maintaining a lewd house,

for the practice of fornication." She was sentenced to four months in the Laramie County Jail by the district judge.

On appeal, the case was reversed on the basis that Hamilton was entitled to have the

sentence determined by the jury. Hamilton continued to operate her house. In 1879, one of the

clients attempted to murder one of the inmates, Ida Snow, by choking her. Snow's screams aroused

others in the house and her assailant Edward Malone was shot to death by Charles Boulton. The death of

Malone was found by the jury to be justifiable homicide. Mrs.

Snow recovered from her injuries and as shown by the 1880 census was soon back at work. Snow is, perhaps, an example of the

difficulties of widowhood in the 19th Century. Snow, an Irish immigrant, was widowed by age 27 and was,

thus, apparently forced, far from home, into a life of degradation and shame, to die "unknelled, uncoffined, and unknown." [Lord Byron,

Childe Harold, Canto iv, stanza 179.]

Certainly other cities elsewhere did use the keeping of bawdy houses as an oppotunity to enhance municipal revenues.

Thus, notwithstanding that a Texas law made illegal the keeping of bawdy houses, San Antonio, the

home of Fannie Porter, hostess to members of the Wild Bunch, actually issued licenses for keeping of

such facilities. Ultimately, the Texas courts held that the ordinance providing for

licensure was itself illegal. One madam after finding out that

the City licensing ordinance was invalid, sued to get back her

$500.00 licensing fee.

Next Page: Laramie Continued.

|