|

The TA Ranch

Following the killing of Nick Ray and Nate Champion, the regulators rested at a friendly ranch and the following day headed out in the direction of

Buffalo. The Regulators had stationed Phil DuFran, formerly Horace Plunkett's foreman, in Buffalo to spy on the town. Outriders were warned

by DuFran of the approach of a posse of 150 armed men under the command of Andrew S. "Arapahoe" Brown, a former captain in the

Confederate Army. Sam Clover, a reporter for

the Chicago Herald covering the expedition, decided that he did not need to stick around and took off

for Buffalo. Fortunately, he had a friend in the military stationed in Buffalo who vouched for him. Richard M.

Allen, the assistant manager for the Standard Cattle Company, determined that discretion and

good sense was the better part of valor and also left for Buffalo. Allen was less fortunate. He left his horse at the livery stable and attempted to depart on the

next stage. Both he and the brand on his horse were recognized. He was removed from the stage and taken into

custody. The stage left without him.

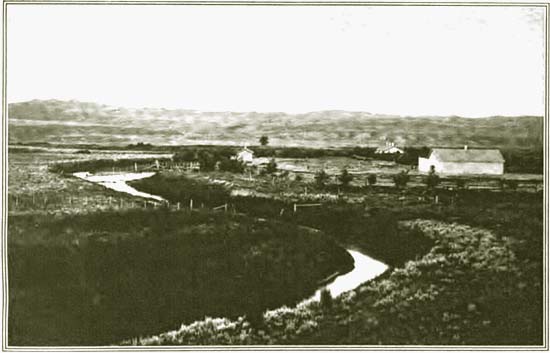

The TA Ranch, 1890's, looking east.

Back south of town, Major Wolcott, resuming commnand,

ordered, over the objection of Smith and Canton, a retreat to the TA Ranch about 12 miles from Buffalo. The TA Ranch was ideally

suited for defense. The house already had a 7 ft. fence around it and was situated in a bend in Crazy Woman

Creek. Behind the house was an ice house which would provide a defensive outpost.

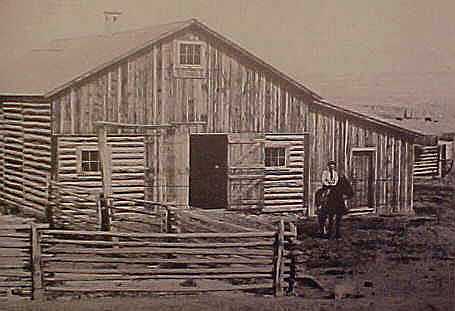

The Stable at the T A

To the

west of the house was the stable. In the loft, the regulators drilled holes to provide gun ports, visible below the loft window in

the photo above. To the west of the stable was a knoll on which the regulators undertook the construction

of a fort. A defense breastwork was also constructed to the rear and east of the house.

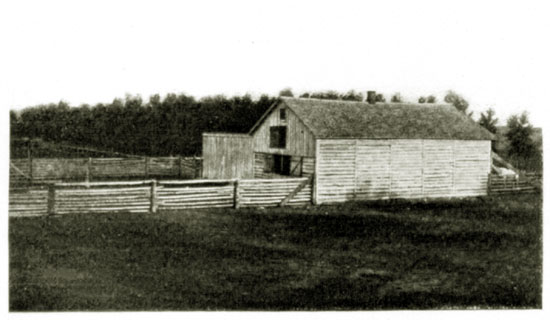

The Stable at the T A.

Soon the posse arrived. The settlers began the construction of rifle pits. Considering the defensive position of the T A, Araphaho Brown realized that a direct frontal assualt on the

ranch would be too costly. The men would not tdubt be simply mowed down by the fire power of the

regulators. It would probably require

a cannon to blow the regulators out of their position. Brown, who was a blacksmith by trade, started to build a homemade cannon. At the

same time, some cowbys headed toward Fourt McKinney fifteen miles away with the thought of borrowing or stealing a cannon from

the military. Brown's homemade cannon unfortunately blew up.

The Corral at the T A.

Ultimately, the Sheriff's posse had approximately 200 men.

In Buffalo, the hardware store was opened with its owner furnishing

amunition and weapons to anyone who would join the posse. The ladies of the town set up a kitchen, dispatching

food by wagon to the men. For two days there was a standoff. John J. Baker, a waddy in the posse, later recalled in

an oral account given as a part of the Federal Writers' Project, that the regulators had better weapons than

the posse. The posse had only ordinary guns and six-guns, but the regulators had high-powered rifles. Thus,

the sheriff's men could not get within range. There was one exception. In

the posse was one old "rawhide" with an old muzzle loading single shot gun. Baker recounted:

"That rawhide was as cool as a steer's nose and all he did was load that

buffalo rifle and shoot. While loading the gun he would chew steadily on a

cut of 'baccy. He would pack the powder and ball keeping his jaw working in time

with the up and down movement of the ramrod. When he got her all set and a cap

on the firing pit, he would turn his head and let out a squirt of 'baccy juice and

raise the gun and BOOM it would go and a ball would hit a door or window every time

he shot. * * * * The old fellow kept his work up for two and a half days. He sent

a waddy to his home with orders to his wife for ammunition and for her

to get to making bullets and a steady supply kept coming. She was on the job

doing her part too.

Although the

Wyoming Inland Telegraph Company was making every effort to get the line to

Cheyenne open, messages were unable to get through to Cheyenne. On Tuesday, a message finally reached

Acting Governor Amos W. Barber, yet no reply came from Cheyenne.

Map of the Seige of the T A Ranch.

From within the beseiged T A, Mike Shonsey rode out under a white flag. The sheriff's men though he wanted to

parley, but then Shonsey made a break for it. He was able to get

through the surrounding lines and rode 100 miles further to the south where a telegraph

line was open. With a message concerning the dire straits the regulators found themselves, action was

taken by Acting Governor Barber. Certainly, among those beseiged were some who were not without

political influence. W. C. Irvine and Hubert E. Teschemacher had been members of the

1889 Constitutional Convention. Acting Governor Barber promptly telegraphed Senators J. M. Carey and F. E. Warren in

Washington, who in turn rushed to the White House and aroused President Harrison from his bed.

Presidential Orders went to Fort McKinney to relieve the seige and take the regulators into

custody.

Movable breastwords

On Wednesday morning like the scene from MacBeth when Birnam Wood to Dunsinane came, the beleaguered

regulators looked out and saw one of the breastworks moving toward them. Baker, explained:

"The second night we held a talk feast on ways and means. The old rawhide offered

a plan. If my mind is working correct I would say the old fellow's name was Boon.

"Fellows in them thar wagons are some dynamite. I reckon them skunks calculated on blowing up some ranch with it.

This outfit it as good as any to do the blowing and the time is fitting. All you waddies that can put a hand on an ax get

hold of one and go down to the creek bed and start cutting. Cut logs about 15 feet long and six inches thick.

The rest of you all that are not busy mount your critters and drag the

timber up here. What we are aiming to do is put them timbers tied to the hind

end of them wagons and make a moving breastworks. We'll push the wagons

backwards towards the buildings until we are in throwing distance and

then throw the dynamite into the pits. That will clean them skunks out of thar.'

"I started at once for axes at the various ranches. By mid-night there

were cutters working and it was not long until timber began to be placed on

the ground. We tied the logs with our ropes to the rear end of the wagons

and by daylight had our breastworks ready. At daylight we started to push

the wagons ahead of us moving slowly towards the ranch buildings a short

distance at a time. There was only 60 of us that could get shelter besides

the pushers and we kept up a steady fire. Among us was the old Buffalo gunner.

The defenders observed the wheels and realized that the freight wagons used by the

regulators, had been coverted into a movable breastwork and from which the dynamite

brought in by the regulators would soon be lobbed. Baker estimated that the men on

the movable breastworks were within a half hour of being within throwing range.

In the distance, however, a bugle was heard, signaling the arrival of the

6th Cavalry led by Col. James Judson Van Horn. Beneath a white flag, Major

Wolcott, gave a bow to Col. Van Horn, and offered his surrender to the

6th Cavalry, but refused to surrender to Sheriff Angus. Angus, however, secured the agreement

that the expedition would be turned over to Civil Authority for trial. The prisoners were

sent to Fort McKinney. Authorities fearing the wrath of the local citizenry, transferred the

prisoners to Fort D. A. Russell for safe keeping. Their fears may have been

justified, for a few days later the barracks at McKinney were bombed by three cowboys who

were allegedly members of the "Red Sash Gang." T. Joe Cahill, who later knew many of the Cheyenne cattlemen

involved in the invasion, expressed the opinion in a 1955 interview, that had not Col.

Van Horn arrived when he did, the Invaders would have been "exterminated" within an hour.

The Court held that the regulators probably would be unable to receive a fair trial in

Buffalo and, thus, transferred venue to Laramie County. In 1890, Johnson County had but a population of

2,357 and in 1900 only four more. The cost of feeding and housing the inmates was visited upon the

nearly empty County coffers. Thus it was that the County literally could not afford the

cost of the prosecution. By the time the case was called for trial the County owed more than $18,000 and the

case was dropped. That, however, did not end the tale.

Next page, The aftermath.

|