|

Town Square looking southwest towards intersection of Broadway and Cache, approx. 1940

Closeups of the hardware store, Lumley's, the Bluebird and the

telephone company visible in the above photo are on a previous page.

All, including the gas station at the

corner of Broadway and Cache, are now gone. Indeed, as indicated in the next photo, the

scene, due to the growth of the trees, is totally different.

Town square looking southwest, 2003, photo by Geoff Dobson

There are three features besides the scenery which disinquish Jackson from other western towns: The Square, officially known as

George Washington Memorial Park; the Arches in the Park; and the Million Dollar Cowboy Bar. The first of the Arches was constructed in 1953 by the Rotary Club. The remainder

were constructed in 1966, 1967, and 1969. The northeast corner pictured above is now the scene of the Shootout discussed on the previous page.

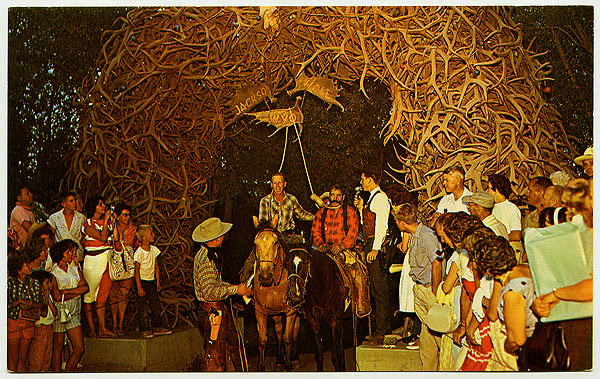

Hanging of Clover the Killer, northeast corner of Square.

Over the years the script for the shootout has considerably changed. The hanging of Clover was discontinued in the mid-1970's. Up until about

1978 it ws the practice not to solicit for funds. Now the had is based. The bad guys are now shot, not hanged. A town drunk wanders through the scene. The music is now a medley

of Western movie themes such as from the "Magnificent Seven." In order to fund the increasing budget, the hat is passed and before the drama ensues there are pitches for the sponsors.

Safety warnings and disclaimers are now given.

owever, it still attracts an afternoon crowd.

The most distinctive feature of the Square are the four elkhorn arches on each of the four corners of the park. The first of the arches was constructed by the local Rotary Club in 1953 on the Southwest corner.

The remaining arches were constructed in 1966, 67, and 68. As of 2013, the Rotary Club has raised funds and is planning the reconstruction of the arches.

The antlers are gathered by boy scouts in the spring after the antlers have been naturally shed. A change in th arches over the years has been the facing of

the bases with stone. The Square is also marked by two other monuments, a monumennt dedicated to the memory of John Colter and the war memorial dedicated to those from

Teton County who died in various wars from the Spanish American our recent wars.

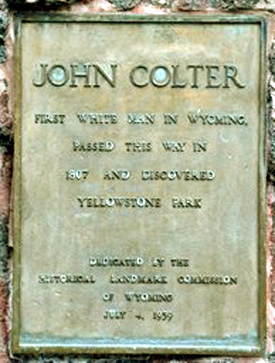

Colter Monument at foot of flag pole, Town Square, 1913, Photo by Geoff Dobson.

The Colter monument was originally constructed in 1939. The flagpole was originally in the center of the square but was moved about 1976 when the War Memorial monument was constructed.

Flagpole in Square, approx. 1939, prior to being moved.

At the time of the construction of the War Memorial, it was noticed that although the Square was denoted as the

George Washington Memorial Park in 1932, no markers had been installed indicating that the park was in honor of the Nation's first

president. Accordingly, in 1937 a small tablet with Washington's name was installed on the back of the Colter Memorial. The nation's first

president therefore takes a hind seat to John Colter. Even less honored in the park is David Jackson after whom the town is named.

Plaque on Colter Monument Plaque on Colter Monument

John Colter was a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The expedition itself never entered Wyoming. On the way back from

Oregon, Colter received permission to leave the expedition. After some brief exploration he headed back to Missouri on his own and came across to the Upper

Missouri led by Manuel Lisa. He was employed by Lisa to explore areas. It is generally believed that he found his way up the Stinking Water to the area of present-day Cody and then proceeded

south to the area of present day Dubis. From there he found his was into Jackson's Hole by way of either

Union Pass or over Togwotee Pass. From there his route is somewhat uncertain but, based on the discovery of a stone bearing his name and the date

1808 in Idaho, he may have crossed over Teton Pass and then up along the western edge of the Tetons and then back into present day Yellowstone Pass. He then apparently followed the

Yellowstone back to Manuel's Fort where he rejoined Lisa's party. It was on this trip or a subsequent trip into the Yellowstone that Colter made what has since been forever known as

Colter's run. John Bradbury in his 1819 "Travels in the Inerior of America" Described the run.

Colter's was traveling by canoe with his partner Potts but encountered unfriendly Blackfeet. Colter was taken prisoner. Potts was killed:

[Potts} was instantly pierced with arrows so numerous that, to use the language of Colter, "he was made a riddle of."

They now seized Colter, stripped him entirely naked, and began to consult on the manner

in which he should be put to death. They were first inclined to set him up as a mark to shoot

at; but the chief interfered, and seizing him by the shoulder, asked him if he could run fast.

Colter, who had been some time amongst the kee-kat-sa, or Crow Indians, had in a considerable

degree acquired the Blackfoot language, and was also well acquainted with Indian customs. He knew

that had now to run for his life, with the dreadful odds of five or six hundred against him, and those armed Indians; therefo he cunningly replied that he was a very bad runner, although he was considered by the hunters as remarkably swift. The chief now commanded the party to remain stationary, and led Colter out on the prairie three or four hundred yards, and released him, bidding him to save himself if be could . At that instant the horrid war whoop sounded in the ears of poor Colter, who, urged with the hope of preserving life, ran with a speed at which he was himself surprised. He proceeded towards the Jefferson Fork, having to traverse a plain six miles in breadth, abounding with prickly pear, on which he was every instant treading with his naked feet. He ran nearly halfway across the plain before he ventured to look over his shoulder, when he perceived that the Indians were very much scattered, and that he had gained ground to a considerable distance from the main body; but one Indian, who carried a

spear, was much before all the rest, and not more than a hundred yards from him. A faint gleam

of hope now cheered the heart of Colter; he derived confidence from the belief that escape was

within the bounds of possibility; but that confidence was nearly fatal to him, for he exerted

himself to such a degree that the blood gushed from his nostrils, and soon almost covered the

forepart of his body.

He had now arrived within a mile of the river, when he distinctly heard the appalling

sound of footsteps behind him, and every instant expected to feel the spear of his pursuer.

Again he turned his head, and saw the savage not twenty yards from him. Determined if possible

to avoid the expected blow, he suddenly stopped, turned round, and spread out his arms. The

Indian, surprised by the suddenness of the action and perhaps of the bloody appearance of

Colter, also attempted to stop; but exhausted with running, he fell whilst endeavoring to

throw his spear, which stuck in the ground and broke in his hand. Colter instantly snatched

up the pointed part, with which he pinned him to the earth, and then continued his flight.

The foremost of the Indians, on arriving at the place, stopped till others came up to join

them, when they set up a hideous yell. Every moment of this time was improved by Colter, who,

although fainting and exhausted, succeeded in gaining the skirting of the cottonwood trees,

on the borders of the fork, through which he ran and plunged into the river. Fortunately for

him, a little below this place there was an island, against the upper point of which a raft of

drift timber, had lodged. He dived under the raft, and after several efforts, got his head

above the water amongst the trunks of trees, covered over with smaller wood to the depth of

several feet. Scarcely had he secured himself when the Indians arrived on the river, screeching

and yelling, as Colter expressed it, "like so many devils." They were frequently on the raft

during the day, and were seen through the chinks by Colter, who was congratulating himself on

his escape, until the idea arose that they might set the raft on fire.

In horrible suspense he remained until night, when hearing no more of the Indians, he

dived under the raft, and swam silently down the river to a considerable distance, when he

landed and traveled all night. Although happy in having escaped from the Indians, his situation

was still dreadful; he was completely naked, under a burning sun; the soles of his feet were

entirely filled with the thorns of the prickly pear; he was hungry, and had no means of killing

game, although he saw abundance around him, and was at least seven days journey from Lisa's Fort,

on the Bighorn branch of the Roche Jaune [yellowstone] River.

Another version, has Colter rather than hiding under a raft of trees, has him taking refuge in a beaver house until the

Indians departed. Chittenden concluded that the Indians were in actuality Gros Ventres.

Colter retired from the mountain man business and died sometime in 1812 or 1813. The exact date of death or the cause is

uncertain. Hiram Chittenden notes that his death was apparently prior to December, 1813. But Chittenden concluded,

"We only know that in running away from his savage foes he soon fell victim of that dread enemy from whom no one escapes."

Statue of Albert J. "Stub" Farlow topping War Memorial,

George Washington Memorial Park, Jackson, 2013. Photo by Geoff Dobson

The War Memorial is unique. Most war memorials have a statue of a doughboy, Civil War soldier or other soldier. A memorial on the Capitol grounds in Cheyenne

depicts a Wyoming soldier from the Spanish-American War taking the oath.

The Memorial in the square is topped by a statue by Bud Bollen, Jr. depicting Albert Jerome "Stub" Farlow (1886-1953), a Lander Rancher, rodeo

cowboy, rodeo producer, and Fremont County deputy sheriff. But the reader asks, "Who is Farlow?" If Landerites are to be believed,

Farlow is the most famous cowboy of them all, far more famous than John Wayne, Roy Rogers, or the Lone Ranger. Other than the images of Mount Rushmore depicted on the

South Dakota license plates, he is the only person

depicted on a license plate and the only cowboy on American coinage. Indeed, he is also depicted on a large sign on a

prominent Cache Street business. Farlow is discussed with regard to Cheyenne Frontier Days,

Casper, and Thermopolis. Stub is regarded by some (primarily from Lander) as the cowboy depicted on the Wyoming license plate and quarter dollar. As far as the writer can tell,

Stub had absolutely no connection with Jackson. The horse did, however, have a connection.

If Landerites are correct and Stub is on the license plate, then

Stub is riding a bronc named "Deadman." Deadman at one time belonged to the Jackson Hole Frontier Association who sponsored

the Jackson Rodeo prior to World War I and provided the bucking bronc for the initial War Bonnet Roundup Rodeo in Idaho Falls where Stub is alleged to have

ridden Deadman. Other candidates for the bucking horse and rider are Gary Holt on Steamboat, Eddie McCarty on

Silver City. See Steamboat.

Next Page: Jackson continued, West Broadway.

|