Robert Kletzing Homestead.

Most of the houses on the Flats were modest as was that of promotor Robert Kletzing. As suggested earlier,

promotion was subject to exageration. Pomotors, as observed by Charles A. Dalich in this "Dry Farming Promotion in Eastern Montana (1907-1916)," Theses, Dissertations, Professional

Papers, University of Montana Graduate School (1968), the promotors "performed feats of geographic legerdemain" in describing the weather, "rainfall figures and describtions of soils

were grossly inaccurate." Dry farming required a combination of factors to be successful. Foremost was sufficient land. Homesteads were increased in size from 160 acres to 320.

The Ross Burhans family expanded their acreage from 300 acres to approximatley 2000 by various members of the family taking out

their own homesteads and by cash entry. Larger acreage permitted the crops to rotate allowing conservation of water. Rpbert Kletzing only owned 160 acres.

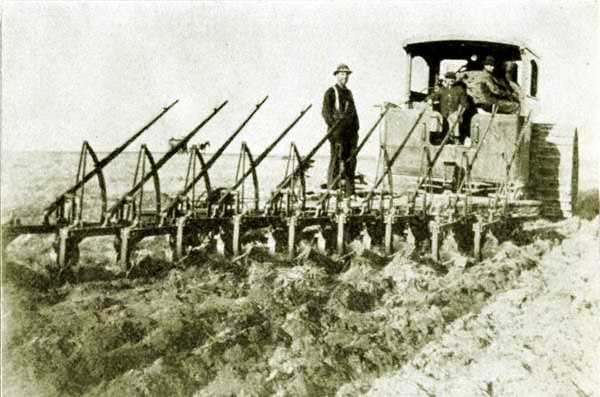

The plowing needed to be "deep plowing" im the fall which permitted roots to reach deeper to moist soil. Deep

plowing required large teams or the use of a tractor. Either required money. Kletzing had neithr. Although he was one of the first

to actively promote Iowa Center, he was also one of the first to leave.

Apparently unknown to Chugwater residents, Kletzing was less than successful in Iola. He had been a teacher and with the advent of deafness wnet into

business for himself. He had to file for bankruptcy. His two sons had to be emancipated from the disabilities of minority. They provided financial support for his venture in

Chugwater. He made no money. He thus traded the Iowa Center lands for timber lands in

Lane County, Oregon which in turn was sold and the proceeds put into yet another business venture which was subject to a

mortgage. One creditor obtained a judgment against him, but it proved to be uncollectable. For details see

Martin v. Thomas, 74 Or 206, 144 Pac 684 (1914)

Archie Blow plowing on his gasoline tractor.

The soil was also important. Soil which was loose could in hot dry winds be subject to wind erosion. It was, however,

a deep plowing was necessary, but it also increased the evaporation.

Steam Plow owned by brothers Grover H. Meeker and Herbert L. Meeker.

The Meeker Brothers came in 1910 from Iowa and each proved up their claim on the same day in 1913, each

witnessing for the other.

Alexander L Macklin, his wife Sarah and his daughter Sadie .

The Macklins also came from Iowa and arrived in 1910. Alexander proved up lhis claim in 1914. He was one of several that actually stayed in the

Chugwater area. With children, schools on the Flats were necessary. The first school on Iowa Flats was established in 1910 in the

front room of the Burhams homestead. The Burhams, father and son, ultimately acquired about

3,000 acres. Soon a one-room school house was constructed. One-room schools were common in rural areas. By 1916, there were 55 school houses in Goshen County with 89 teachers between

them.

Slater School in Platte County, a short distanct north of Chugwater Flats.

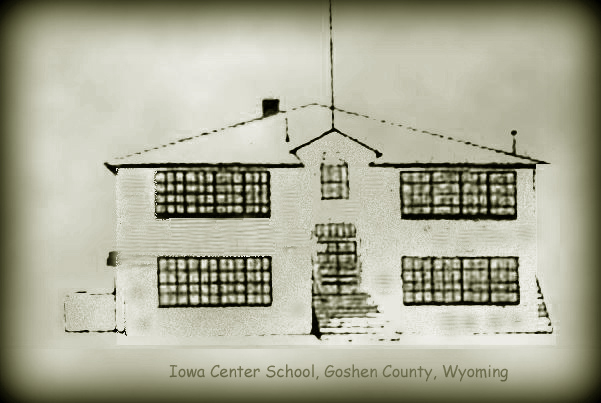

In 1913, the school district was consolidated with several other one-room schools being

brought to the location. In 1928, a two-story wooden school building was constructed. The following year it was burned but was replaced with a similar building but with

an outside fire escape from the second floor.

Iowa Center School.

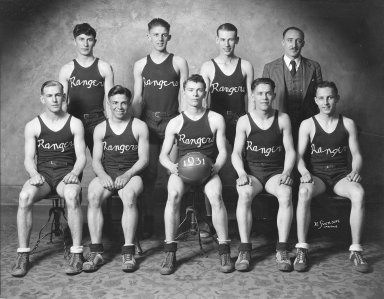

The new building included an inside regulation basketball court. Prior to 1932, the Iowa Center Rangers competed in the annual

high school tournament in Class D. Others competing in Class D included Medicine Bow, Big Piney, Egbert, Carpenter, and Fort Laramie. In 1931, the Rangers made it to the Seventh

Round but were beaten out by Egbert.

Iowa Center Rangers 1931.

By the 1925-26 school year the school attained its maximum student enrollment of 98 students. and was indeed the largest rural school in

Goshen County. The growth was perhaps as a result of consolidation. However, The Flats had begun to lose population before 1920. The post office was established in

1911 and closed in 1916. By 1940, the Flats were described by writers for the WPA Guide to Wyoming: "Now dozens of farms are deserted; windows are boarded up and machinery stands rusting in the

barn yards." With the decline in the population of the area served, high school was discontinued in 1944 with the graduation of two. The school coontinued as an elementary

school until 1960 when the school was closed, torn down and the property sold.

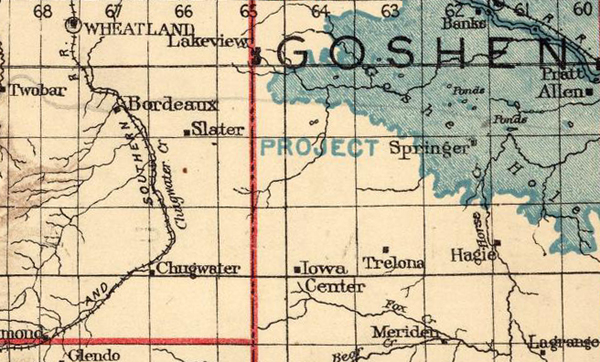

1912 map showing locaton of Iowa Center in relation Chugwater and nighboring towns.

Today, Iowa Flats and Iowa Center no long appear on most maps, seemingly swallowed by Goshen Hole.

Only a

monument and the school front steps mark the school's former location. Heading east from Chugwater along Lone Tree Road (State road 313), one will pass a few ranches and farmsteads. Supposedly,

in a dyslectic manner Lone Tree Road takes its name from Trelona. Trelona had a post office by 1889, but mail service was discontinued in 1912 and the area was served by the Meriden Post Office. By 1940,

Meriden consisted of a gas station, store, and the post office with 30 post office boxes. Meriden remains small.

Distant view of Meriden, Wyoming.

Hagie was named for homesteader and first postmaster Alvin Hagie. By 1922 Hagie had a population of 3. The post office was moved

to Hawk Springs in 1928.

In 2010 a 536 page application was made to construct a windmill farm on the Flats. Winter wheat is still grown on the Flats but to an extent uncultivated areas are

short grass prairie, buffalo grass and sage. Although there are a few homesteads, the area is desolate with a few collapsed

homesteads and a little wildlife. The sites of other homesteads are marked by the remains of windmills,

trees which were once part of a windbreak, foundations, and from satellite images in which

the outlines of house sites can be detected. Although the windmill application was granted, it was allowed to lapse. In advance of the 2016 election,

a proposal was made to move the Iowa Center Precinct voting station out of the precinct itself and combine it with

Hawk Springs. In the Iowa Center Precinct presidential race, 25 votes were cast, 22 for Donald Trump, two for Hillary Clinton and one for Gary Johnson.

Chugwater Flats still appears in the DeLorme Wyoming Atlas & Gazetteer. The Meekers are perhaps remembered in the name of

Meeker Road. Remembrances of Chugwater Flats were brought back in Thomas Hornsby Ferril's

"Something Starting Over:"

I know how it smells and feels to sift the ages,

But something is starting over and I say

It's just as beautiful to see the yucca

And cactus blossoms rising out of a Ford

In a sage arroyo on the Chugwater flats,

And pretend you see the carbon dioxide slipping

Into the poverty weed, and pretend you see

The root hairs of the buffalo grass beginning

To suck the vanadium steel of an axle to pieces,

An axle that took somebody somewhere,

To moving picture theaters and banks,

Over the ranges, over the cattle-guards,

Took people to dance-halls and cemeteries —

A couple sitting on trunk of car on the Chugwater Flats. Photo courtesy of Sharon Lawrence.

All across the Great Plains the same loss of population was experienced as a result of the droughts.Typical was

Dallas, South Dakota, which went from a populaton of 1,277 in 1910, to 705 in 1920, and

428 in 1920. As of 2015 it had an estimated population of 122.

As noted with regard to the Tallmadge and

Buntin Land Co. on a preceding page, a drought hit the state in 1910. A worse droght hit beginning about

1920 leading to the Dust Bowl. Dry Farming generally

needs a minimum of 15 inches of rain a year. Thus, the promotions of dry farming

turned to dust with the drought and the state marked a substantial decline in

acreage devoted to dry farming. Additionally, many homesteaders, in what is now the Thunder Basin

National Grasslands, were relocated by the Federal

Government's Relocation Administration in the 1930's. In some instances they were relocated to

areas which were already developed. In others, they were paid $2.05 to $2.21 an acre for

their homesteads. The Relocation Administration was headed by

Rexford G. Tugwell, a former Columbia University professor. Dr. Tugwell was a believer in

centralized planning having, apparently, been inspired by the Soviet model. In the 1920's

Dr. Tugwell, with others, made the pilgramage to Moscow for a personal audience with

Joseph Stalin. Dr. Tugwell justified the actions of the Relocation Administration in government financed films such as

The Plow That Broke the Plains. The film, an artistic success, blamed the 1930's droughts on the

actions of the farmers. It should be noted, however, that dry farming successfully continues even today in some

areas of eastern Wyoming such as Niobrara County.

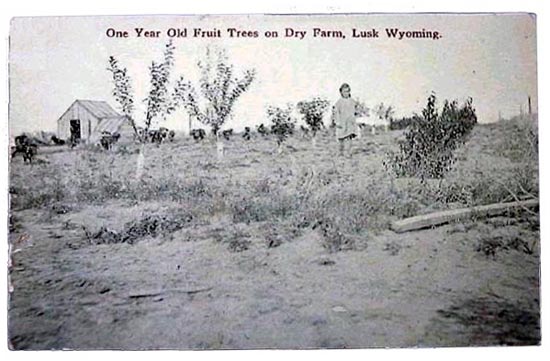

Dry Farming Orchard Near Lusk, approx. 1910.

Thus, for the most part, the State remains dependent on irrigation for its agriculture. Other privately developed

irrigation plans in addition to those of Tallmadge and Buntin, however, have proven not to be profitable for the promoters.

Wm. F. Cody's plans for irrigation in the Bighorn Basin made agriculture possible, but provided him with

nothing but financial losses. By the same token, the Wyoming Development Company provided

irrigation for some 50,000 acres near Wheatland. Wheatland has prospered, but the company was awash

in red ink, losing more than $1,500,000 in 50 years.

But while some talked of the weather, others tried to do something about it. The idea that

the weather in the American West could be changed started at a very early time.

Dr. Ferndinand Hayden in 1868 predicted that the entire climate could be

changed if only each settler would plant 10 to 15 acres of trees for each

160 acre parcel. Others predicted that the disturbance of air by trains would

produce rain or that plowing of the earth itself produced rain. Thus, Gen. G. M. Dodge in an

1888 speech in Toledo, Ohio, claimed that "The building of the Pacific roads

has changed the climate between the Missouri River and the Sierra Nevada." Gen. Dodge explained:

Since the building of these roads, it is calculated that the rain belt

moves westward at the rate of eight miles a year. It has now certainly

reached the plains of Colorado, and for two years that high and dry state

has raised crops without irrigation, right up to the foot of the mountains.

Salt Lake since 1852 has risen nineteen feet, submerging whole farms along its

border and threatening the level desert west of it. It has been a gradual

but permanent rise, and comes from the additional moisture falling during

the year rain and snow. Professor Agassiz, in 1867, after a visit to

Colorado, predicted that this increase of moisture would come by the

disturbance of the electric currents, caused by the building of the Pacific

railroads and settlement of the country.

[Writer's note: Professor Agassiz, 19th Century naturalist, Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz (1807-1873),

professor of zoolology at Harvard University and an opponent of Darwinism.]

Others, attempted to produce rain. Most rain making efforts were prompted by the 1890 publication of War and

the Weather by Edward Powers, which contended that rain was caused by the concussions of

loud noises, such as produced by cannons or thunder. The theory was that the

noise of the thunder produced the rain. The theoretical explanation for the concussions causing rain was

given by Sir William Moore, K.C.L.E., Q.H.P. in an 1891 paper, "Famine: Its Effects and Relief,"

Transactions of the Pidemiological Society of London New Series, Vol. XI:

Clouds are masses of minute vesicles. The liquefaction of vapours is their passage from the

aeriform to the liquid state. Liquefaction may be due to three causes -- cooling, chemical affinity,

compression. When an explosion occurs, compression results; minute vesicles of moisture coalese and

become larger drops, and then they fall.

Sir William conceded, however, that the amount of rain so produced would never suffice for the

cultivator's purpose and, instead, governments should rely upon irrigation.

Rainmaking by explosions from baloons, 1891. Rainmaking by explosions from baloons, 1891.

In 1891, Frank Melbourne,

an Irishman known variously as the "Rain King," the "Rain Wizard," and later by skeptics as the

"Rain Fakir," undertook to produce rain in

Cheyenne on a contingent fee basis; that is, if he made it rain he would be paid $150.00. He claimed that

for ten years he had successfully produced rain in the Outback of Australia. Among those

contributing to the pot were F.E. Warren and Joseph Carey, who each contributed $10.00.

Setting up in a barn off of 23rd Street, Melbourne confidently predicted he would produce rain on

Sunday (so as not to interfere with work), September 1. As predicted the rains came and

Melbourne was paid (it also snowed in Casper). He then predicted that he could make it rain again by Sept. 6 for another

$100.00, far less than the $1,000, he received the following year in Fort Scott, Kansas. The second

effort was less sucessful and Melbourne departed for Utah. Later unsuccessful efforts were

also made in Holyoke, Colorado, before Melbourne committed suicide in a Denver hotel.

Elsewhere, others attempted to make rain. The Rock Island Railroad employed one of its dispatchers, Clayton B.

Jewell, on a special train to produce rain. The train was available to drought parched

communities for $500.00. In Texas in 1891, some $9,000 in federal funds were expended

by Robert G. Dyrenforth in an unsuccessful effort to produce rain using explosive

balloons and kites. The explosions were thought to create "air-quakes," the compressive nature of

which created the rain. Governor James Hogg took a personal interest in the effort and planned on attending

some of the tests. Dyrenforth left the state before the governor could arrive. Robert J. Kleberg of the King Ranch also employed a

rainmaker. In most of the west, the employment of rainmaking magicians with bottles of

mysterious chemicals or explosives had ended by 1894. Yet, even as late as 1915, public funds were

spent in some areas on an effort to produce precipitation.

In San Diego that year, the

City employed the self-styled "Moisture Accelerator" and sewing machine salesman, Charles M. Hatfield to shower the City's reservoir with rain for a fee

of $10,000, payable when the reservoir was filled. In 1905, Hatfield had been employed by the

government of the Yukon Territory to produce rain for placer miners. There he was

unsuccessful. For San Diego, Hatfield constructed a twenty-foot tower near

the reservoir from which smoke emitted upwards from his "evaporating tanks." Sure enough, the rains came, but with a vengence.

It rained for five days.

The reservoir filled, several dams collapsed, a train was derailed by the force of the

water, and houses were washed off their foundations. Efforts to reach Hatfield to get him to

stop the rains were unsuccessful, the telephone lines had washed away in the

deluge. Then ensued the flood of lawsuits. The City contended that the flood was caused by an

Act of God and, therefore, it was not liable for the damages caused by the floods; nor was it liable to

Hatfield for the $10,000. Hatfield argued that the City should have taken

precautions for his success. In reality, of course, the production of rain and the efforts of

rain fakirs such as Hatfield, Melbourne, and Jewell, was more a matter of

coincidence. In some cases the rains came before the

wizard could start his efforts; if only he started a day earlier he would have gotten credit.

In other instances such as Melbourne in Holyoke, the rains came after the wizard left town; if he had only stayed

around another day he would have been credited.

Next page: Farm Equipment.

|