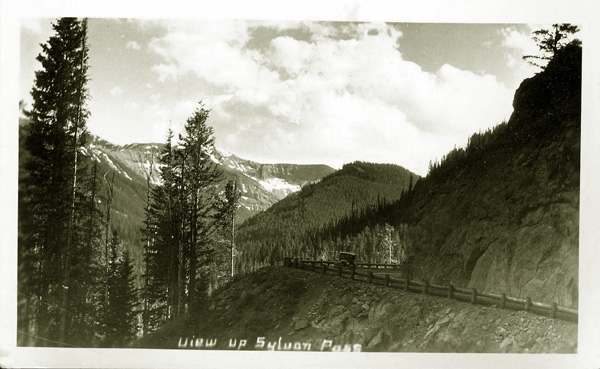

Ascending Sylvan Pass, approx. 1930.

In 1903, Park superintendent Hiram Chittenden described Sylvan Pass:

Sylvan Pass * * * takes its name from the lake, for there is nothing of a sylvan character in the pass itself.

On the contrary it presents a scene entirely unique among mountain passes.

It is like a vast trough, the sides of which are composed of loose rock

that has fallen down from the lofty cliffs above, and now rests on its

natural slope, forming a treacherous foothold even for the wild animals

of the mountains. The great natural obstacles in crossing it have always

prevented it from being much used, either by wild game or the Indians, and

it was not until after extensive exploration that the government engineers

finally selected it for the line of the Eastern Approach across the Absaroka

Divide. Two considerations at length prevailed over the enormous difficulties

of the work—the fact that the pass was nearly 1,000 feet lower than any

other available, and the unique and unusual character of the scenery.

At the very summit of the pass, a rippling waterfall comes down from the

cliffs on the south, and flows into a little pond of great clearness and

depth. Owing to the loose texture of the rock-filled ravine, a large part

of the water that enters this pond flows away by subterranean passages, and

it is full to overflowing only during the spring high water. By the end of

the tourist season it falls nearly ten feet.

The pass is flanked by lofty mountains—Avalanche Peak and Mount Hoyt on the

north, and grizzly and Top Notch Peaks on the south. They rise directly

from the pass to heights of from 1,000 to 2,000 feet.

Descending from the pass by a steep grade, the road arrives, in about a

mile, at a crystal fountain which is probably the largest cold water

spring in the park. It gives egress to the waters which flow out of Sylvan

Pass.

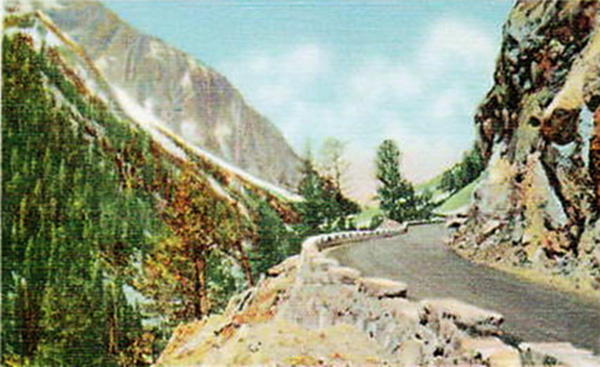

Sylvan Pass, approx. 1920's.

The pass is some 8,524 feet in elevation and provides a first views of Avalanche and Hoyt Peaks to the north,

Top Notch Peak to the South, and Sylvan Lake from which the pass derives its name. One may also

spot the Grand Tetons seventy miles away. In the 1902 Haynes Guide to Yellowstone, it was noted that

on the descent from Sylvan Pass after

pass was reached "one of the finest panorama views of the Park is to be had. Yellowstone Lake occupies the

foreground, and the distant snow-clad peaks of the Tetons, Quadrants,

Electric Peak, Mount Washburn, and the entire Rocky Mountain range within

the Park, outline the horizon." The Guide noted, however that it qas about eighteen miles from the Lake Hotel to Sylvan Pass. Thus, the Guide warned

that although a side trip to this rugged portion of the Park was now

possible " until hotel accommodations are provided, it will be necessary to carry camp equipment,

as it will require nearly two days to visit all the interesting points of this section."

Avalanche and Hoyt Peaks, National Park Service Photo.

Hoyt Peak is named after Governor Hoyt who explored the area, looking for a route to connect Yellowstone to the rest of

Wyoming.

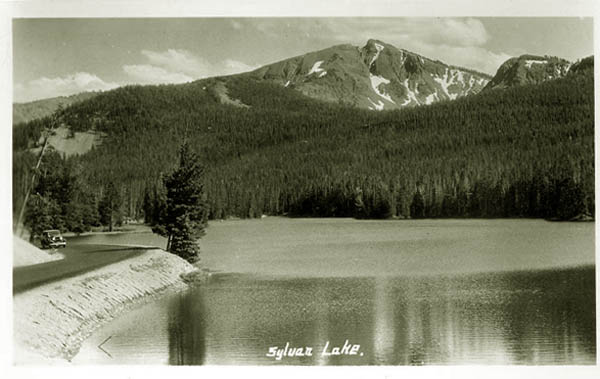

Sylvan Lake, approx. 1927.

Sylvan Lake. Postcard by Haynes, approx. 1930.

Sylvan Lake, approx. 1930.

From the above two photos it is not dificult to see how Top Notch Peak received its name.

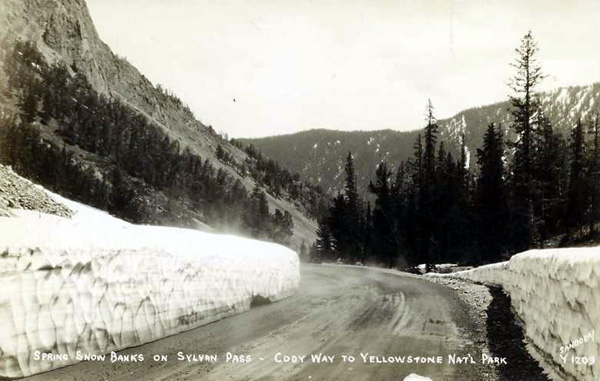

The loose rocks referred to by Superintendent Chittenden in the pass are seen on the two preceding pages.

The loose rocks still

provide problems. The road passes below a sharp precipice of loose rocks or talus.

Sylvan Pass with icy conditions, 1930's. Photo by William Sanborn.

Under wet conditions the mud, talus and

gravel slide down onto the road imperiling motorists.

Vehicles overtaken by gravel side, Sylvan Pass. National Park

Service Photo.

Vehicle overtaken by gravel side, Sylvan Pass.

NOAA photo.

The area can receive as much as 300 inches of snow a year. As a result, in the winter the road is frequently closed as a result of avalanche danger.

Site of avalanches, Sylvan Pass, May, 4, 2017. National Park Service Photo.

The above photo shows the area in which during one 10-hour period in May 2017 some four

avalanches reached the road.

Next Page: Promotion of the Cody Road.

|