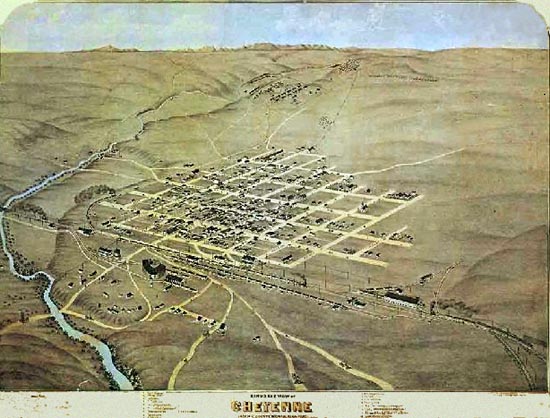

Bird's Eye View of Cheyenne, 1870, looking northwest. In the distance is

Fort D. A. Russell and Camp Carling.

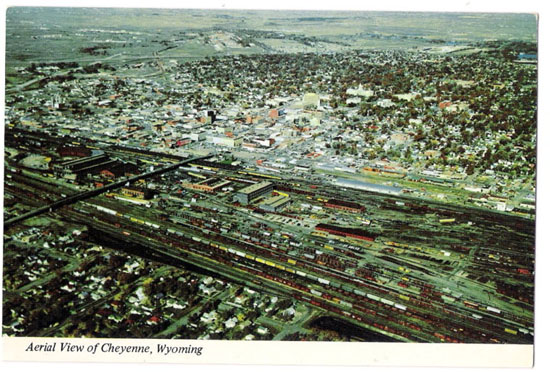

The growth of Cheyenne as a result of its being a transportation hub is indicated by comparing the above

drawing with the following illustrations, all made from approximately the same position..

"Bird's Eye"

view of Cheyenne, 1882, looking northwest.

"Bird's Eye"

view of Cheyenne, approx. 1960, looking northwest.

Freight Train, Cheyenne, undated.

Various writers expressed a very jaded view of Cheyenne in its formative years. A. N.

Ferguson, a surveyor for the Union Pacific, described the city in his diary:

Sunday, April 26, 1868-Our train stopped at a station two hours last night

on account of Indians. Made North Platte a few hours after sunrise where

we had breakfast. This is a very warm morning. Had dinner at Sidney Station.

Arrived at Cheyenne about 6 o'clock p.m. Had supper at Rollins House after

which we walked around town where we witnessed strange sights. The whole

city was the scene of one high carnival-gambling saloon and other places

of an immoral character in full blast-bands of music discoursing from the

fronts of various places-streets crowded with men-and numerous houses

illuminated, and vice and riot having full and unlimited control, making

the Sabbath evening a sad and fearful time instead of being holy and

peaceful. Retired to bed early.

Indeed, Charles Goodnight, himself, viewed the town in a less than favorable light. Years later

he described a town in Texas, Mobeetie, frequented by early buffalo hunters:

"Mobeetie was patronized by outlaws, thieves, cut-throats, and buffalo hunters, with a large per cent

of prostitutes. Taking it all, I think it was the hardest place I ever

saw on the frontier except Cheyenne, Wyoming."

One English novelist, William Black, in his 1877 Green Pastures and Piccadilly expressed

disappointment that the city did not live up to its reputation:

"Certainly, the Cheyenne we saw was far from being an

exciting place; there was not a single corpse lying at

any of the saloon doors, nor any duel being fought in the

street."

Others were struck by the lack of vegetation. Laura Winthrop Johnson noted in 1875

that the principal tree "in Cheyenne was not larger than a lilac-bush, and had to be kept wrapped in wet towels."

But as least there was a tree. Two years before in 1873, Isabell L. Bird described her passage

through Cheyenne:

The surrounding plains were endless and verdureless. The scanty

grasses were long ago turned into sun-cured hay by the fierce

summer heats. There is neither tree nor bush, the sky is grey,

the earth buff, the air blae and windy, and clouds of coarse

granitic dust sweep across the prairie and smother the

settlement. Cheyenne is described as "a God-forsaken,

God-forgotten place." That it forgets God is written on its

face. It owes its existence to the railroad, and has diminished

in population, but is a depot for a large amount of the

necessaries of life which are distributed through the scantily

settled districts within distances of 300 miles by "freight

wagons," each drawn by four or six horses or mules, or double

that number of oxen. At times over 100 wagons, with double that

number of teamsters, are in Cheyenne at once. A short time ago

it was a perfect pandemonium, mainly inhabited by rowdies and

desperadoes, the scum of advancing civilization; and murders,

stabbings, shooting, and pistol affrays were at times events of

almost hourly occurrence in its drinking dens. But in the West,

when things reach their worst, a sharp and sure remedy is

provided. Those settlers who find the state of matters

intolerable, organize themselves into a Vigilance Committee.

"Judge Lynch," with a few feet of rope, appears on the scene, the

majority crystallizes round the supporters of order, warnings are

issued to obnoxious people, simply bearing a scrawl of a tree

with a man dangling from it, with such words as "Clear out of

this by 6 A.M., or----." A number of the worst desperadoes are

tried by a yet more summary process than a drumhead court

martial, "strung up," and buried ignominiously. I have been told

that 120 ruffians were disposed of in this way here in a single

fortnight. Cheyenne is now as safe as Hilo, and the interval

between the most desperate lawlessness and the time when United

States law, with its corruption and feebleness, comes upon the

scene is one of comparative security and good order. Piety is

not the forte of Cheyenne. The roads resound with atrocious

profanity, and the rowdyism of the saloons and bar-rooms is

repressed, not extirpated.

Beer Wagon in front of

Cheyenne Billiard Hall, undated..

The store to the right was operated by George E. Thompson, a boot and shoe maker Thompson arrived in Cheyenne at the

height of its "Hell-on-Wheels" days.

Interior, billard hall, Cheyenne, undated. Note

spittoons on the floor.

Mrs. Bird continued in her description:

The population, once 6,000, is now about 4,000. It is an

ill-arranged set of frame houses and shanties and rubbish

heaps, and offal of deer and antelope, produce the foulest smells

I have smelt for a long time. Some of the houses are painted a

blinding white; others are unpainted; there is not a bush, or

garden, or green thing; it just straggles out promiscuously on

the boundless brown plains, on the extreme verge of which three

toothy peaks are seen. It is utterly slovenly-looking, and

unornamental, abounds in slouching bar-room-looking characters,

and looks a place of low, mean lives. Below the hotel window

freight cars are being perpetually shunted, but beyond the

railroad tracks are nothing but the brown plains, with their

lonely sights--now a solitary horseman at a traveling amble, then

a party of Indians in paint and feathers, but civilized up to the

point of carrying firearms, mounted on sorry ponies, the

bundled-up squaws riding astride on the baggage ponies; then a

drove of ridgy-spined, long-horned cattle, which have been

several months eating their way from Texas, with their escort of

four or five much-spurred horsemen, in peaked hats, blue-hooded

coats, and high boots, heavily armed with revolvers and repeating

rifles, and riding small wiry horses. A solitary wagon, with a

white tilt, drawn by eight oxen, is probably bearing an emigrant

and his fortunes to Colorado. On one of the dreary spaces of the

settlement six white-tilted wagons, each with twelve oxen, are

standing on their way to a distant part. Everything suggests a

beyond.

Others commented on the abounding bar-room characters, but noted that they were in fact

gentlemanly. In April, 1877, Miriam F. (Mrs. Frank) Leslie crossed

the continent with several members of the staff of her husband's newspaper. Mrs. Leslie

noted:

Cheyenne proved itself a fresh and vigorous experience of a true frontier town--streets dark

and suggestive of all sorts of fierce experiences connected with the swarms of swarthy,

rough-clad men, who lounged at every corner and filled every shop, yet never offered to

molest the visitors by word, act or look, although evidently "taking stock" and remarking

upon their unfamiliar appearance.

Mrs. Leslie also noted the ready availability of firearms:

Our first visit was to an ammunition shop to lay

in supplies for a pistol presented to "our" artist upon his journey, that first pistol

which is to every young man now-a-days what the toga virilis was to the Roman youth.

In this establishment we had an opportunity of examining the outfit deemed requisite for a

visit to the Black Hills, in the shape of horribly keen and deadly knives, and firearms

of every size and variety. In fact, it was decided by the experts of the party that in

this one shop was condensed a larger assortment, and more complete arsenal, of deadly

weapons than is to be found in any New York establishment.

With territorial status Cheyenne was made the capital. With the railroad the

city became the jumping off location for freighters and miners heading north to the

Black Hills. In 1876 the Black Hills stage line was established. See discussion of the

Deadwood Stage. Thus, as illustrated in the next view

and the views on the next page, Cheyenne in its early days

was a tad "wild and woolly," but had become more civilized.

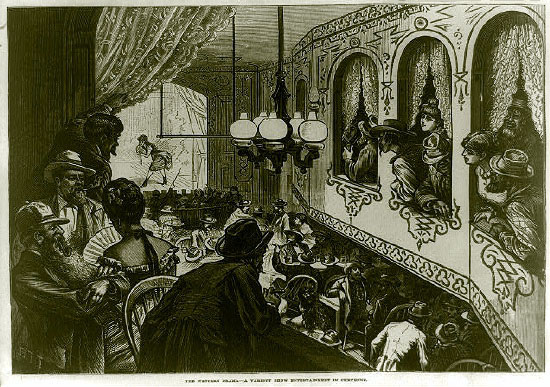

Cheyenne, 1877, woodcut, Leslie's Illustrated News

The above is a portion of a woodcut appearing in 1877 in Leslie's Illustrated News.

The balance of the picture appears on the next page. In the foreground is a freight

wagon and behind it the Cheyenne and Black Hills Express Stage, the famous

"Deadwood Stage," which ran from Cheyenne to Horse Creek, Fort Laramie, Rawhide Buttes,

Custer City and on into Deadwood.

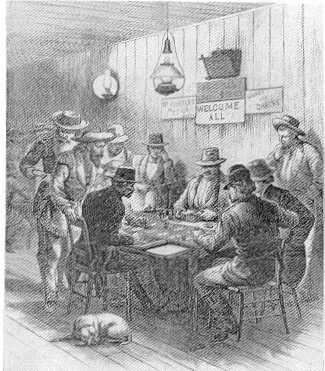

"Bucking the Tiger" in a Cheyenne Gambling Saloon, woodcut, Leslie's Illustrated News, 1877

"Bucking the Tiger" in a Cheyenne Gambling Saloon, woodcut, Leslie's Illustrated News, 1877

The characters are playing lansquenet, sometimes referred to as "lambskinnet,"

a variation of faro. The signs behind

the dealer read, "No Markers Put Up," "Faro Game Limit $12.50," and "Money for Checks."

At the very top is the gambling license. The expression "Bucking the Tiger" comes

from the images of tigers frequently printed on the backs of the

faro cards. Efforts were made to curb gambling. In 1888, the

legislature debated the subject. One legislator, Tom Hooper, argued,

"Show me the man who will not gamble in some way and I will show you an imbecile."

Although referring to Cheyenne as "peripatetic and Hadean," Mrs. Leslie described

the calming influence of churches on Cheyenne:

We arrived at Cheyenne in Wyoming Territory on April 21, 1877. Although

originating as a railroad "Hell on Wheels" town, Cheyenne had lost most

of its wild character. In 1867 it was a village of tents, that were

gradually replaced by wooden structures. Although 20 gambling saloons

remain, the influence of the five churches can be felt as all of the

saloons close between 10:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. on Sundays.

Indeed, however, the Legislature, itself, adopted the same closing laws in

1882, but only for towns having a population 500 or more.

[Writer's notes: It is difficult to determine the sense in which Mrs. Leslie intended the term "paripatetic."

Originally, paripatetic meant moving about on foot, i.e. pedestrian. It has since taken on

several secondary meanings, including moving, changing, and Aristotelian from the

practice of Aristotle teaching whilst walking to the Lyceum. Mrs. Leslie's quoted material come from

both her articles appearing in her husband's newspaper and her later book,

Pleasure Trip from Gotham to the Golden Gate in 1877.]

One of the gambling saloons, James McDaniel's theatre and gambling saloon on

Eddy Street (now Pioneer Ave.), impressed Mrs.

Leslie mightily:

Obtaining permission and escort, we first turned our steps to McDaniel's

Theatre, conspicuously advertised as offering a "Great Moral Show," but

whether permanently or for that evening only was not mentioned. Passing

through a bar gorgeous with frescoed views of Vesuvius and the Bay of

Naples, and remarkable for its cleanliness, we found ourselves in the

parquette, so to speak, of the theatre--a large room fitted up with chairs

and tables, for the use of convivial parties, and served by pretty waiter

girls. The stage was narrow, the drop-curtain exceedingly gorgeous, and

statues of the Venus de Medici, and another undressed lady of colossal

proportions, posed strikingly at either wing. At each side of the hall

are tiers of boxes, so called, reached by long narrow flights of stairs

from the parquette; these boxes are closed in, and have each a window,

through which the inmates must project head and shoulders if curious to

witness the performance on the stage; but, as they contain tables and

chairs, it is possible that a glass of wine or lager and social intercourse

may be more the object than spectacular entertainment.

At the head of the stairs is a small bar bearing the notice: "No drinks

retailed here"; and above, there is printed in large letters: "Gents, be

liberal."

Returning through the bar, we passed into the gambling saloon--a large

room, exquisitely clean and orderly, with a bar at the end, and long tables

at each side, arranged for Rouge et Noir, Roulette, Keno, and our national

game of Biblical memory.

McDaniel impressed William Francis Hooker, a bullwhacker, differently. He described

McDaniel as "bald-headed and also smooth of

voice, * * * circulating around among his

top-booted guests like a pastor among his flock, and

you wonder that such a fine-looking, well spoken

man is not in a pulpit instead of a dive." Hooker, The Prairie Schooner, 1918.

Across the street from McDaniel's was Dyer's Hotel. It was reported that when John

Hunton's wagon boss Nathan Williams was in need of additional bullwhackers, he would sit on the

front porch of Dyer's "Tin Restaurant." The restuarant was so-called because when

first founded the dinnerware was made of tin. On the front porch, like a spider for a fly, Williams would wait until cowboys, having been stripped of money by McDaniel, emerged in

need of employment. As a sign-up bonus, Williams would offer a free round of drinks in Dyer's bar.

Interior McDaniel's Theatre

It may be speculated that the reason that the "inmates" of the boxes would engage in social chitchat

or the drinking of the wine was the quality of the performances on the stage. Bill

Nye later observed, "I have seen shows at * * * McDaniel's in Cheyenne, however, where the bar should

have provided an ounce of chloroform with each ticket in order to allay the

suffering." It has been estimated that at the peak of the Deadwood gold rush, McDaniel was

netting over $500.00 a day. McDaniel also opened a theatre in Deadwood and later in Leadville. Regardless, of whether McDaniel

well spoken, he was not always well recieved by his patrons. Twice he was badly injured when customers through him from

the gallery to the floor below. But by the time of Mrs. Leslie's visit, McDaniels had become a model of decorum, not withstanding that the

following year John Irwin was arrested for discharging his revolver in the

theatre.

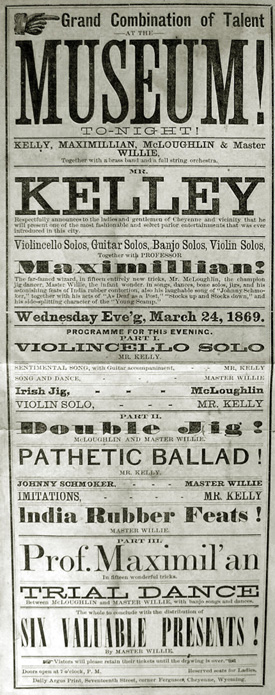

Flyer for McDaniels Museum, 1869 Flyer for McDaniels Museum, 1869

When first started in 1868, McDaniel's attracted customers by letting them view

risque stereographs. John Kelly featured in the flyer was an Irish violinist who first achieved fame playing in the gambling dens of Idaho mining camps.

The nature of Kelly's original act and the saloons in which he performed was later described by

former Idaho Governor W. M. McConnell. Kelly required:

[T]he installation of a swinging stage, or platform, swung by iron rods from the upper joists, several feet above the heads of those who might stand on the main floor below. This platform was reached by a movable ladder, which, after he

had acended, he pulled up out of reach of those below. The object was two-fold: First, when he

located upon his arie, he was removed from the danger of panics which were an almost nightly occurrence, caused from the sportive instincts of some

visitor, who, having imbibed too freely of the regulation vest-pocket whiskey, or having sufferd some real

or imaginary grevances, proceeded to distribute the leaden pellets of a Colt's navy revolver, not only into the anatomy of the offender, but quite

as freqently to the serious if not fatal injury of some innoncent bystander. * * * * His second object was to be above the course of flying missles and thus preserve his violin, which was a valuable one, from the chance of being

perforated by stray bullets.

* * * *

He was a big-hearted son of the Emerald Isle and although untoward circumsances had made him the leading attaction of a den of iniquity, he loved best to play

those tender chords that awakened the memories of other days and sent some of the hearers back to

their lonely cabins up the gulch better men for the hour they has pent under the musician's spell, even in that dreadful haunt McConnell, Early History of Idaho, p. 139-140.

Master Willie was Kelly's adoptive son, a full-blooded Shoshone. In 1863, a company of miners under Jeff Standifer seeking reprisal for raids on mining camps by

Piute Indians, attacked a band of Shoshone killing the entire band except one woman and two boys. The younger of the two

boys was found attempting to nurse from his dead mother. The boy was adopted by Kelly who trained the boy first as a contortionist and later in Irish jigs and to play the

violin. Willie ultimately became the equal of his adoptive father. At the time of the flyer, Master Willie would have been about six years old. The New York Tribune, March 24, 1870, quoting

The St. Joseph Herald descibed Master Willie as able to perform "all the dances of the

modern 'minstrel' including 'Shoo Fly' and the 'Big Sun Flower'" John Kelly and Master Willie appeared twice at

McDaniel's Museum first in March 1869 for two days and later in November 1869 for two days for the

Grand Reopening.

The two later appeared in Australia, England, and Ireland. About 1881, when Willie was 18, the two appeared in Ireland. There, Willie developed a

"congestive chill" and died.

Later, McDaniels' establishment featured a

forty-horsepower Brussels organ which

would blast out Listen to the Mocking Bird. McDaniel later added a zoo and the

"world renowned Circassian girl." The editor of the Star noted:

The Museum still floats on the winds of public favor. Mc's Yankee enery and perserverance excels even Barnum, the Great of New York. Passing last evening we

dropped in to hear the band and found great improvements going on. The Hall is being refitted and

furnished and will be opened with greater effect than ever. We are glad to see this evidence of Mc's thrift and prosperity.

But all good things come to an end. Ultimately, McDaniel's operations went belly-up and he ended up destitute and died

in a park in El Paso. His 1902 obituary from the wire services was short:

James McDaniels.

EL PASO, Tex. April 18-- James McDaniels, an old-time theatrical manager and actor, died to-day at the age of 63 years. McDaniels was

at one time manager of John McCullough's theater in San Franscisco and later owned the McDaniels block at

Cheyenne, Wyo. which was burned, leaving him penniless. His only support in recent years was an

allowance from the Actors' Association. He at one time played with Clare Morris and Frohman.

[Writer's notes: Clara Morris was a well-known 1860's and 1870's actress who appeared on stage with, among

others, John Wilkes Booth. The Frohman Brothers, Charles, Daniel, and Gustave were theatrical producers who organized a system of

road shows and later became motion picture producers.]

The ability of places such as McDaniel's to relieve cowboys of their money was legendary. One cowboy,

Bill Walker, who at one time rode for Arizona's Erie Cattle Company and was later a freighter out of Casper, recalled an

incident in Cheyenne. He noted that at the time,

"Cheyenne had only one real street

then, about three blocks long, but

it was sure a great street of its size. It had

a clothing store with a plate-glass front, and

that store front was the only mirror that a lot of those

cowboys had ever looked into. That burg had plenty of ladies, too,

as well as saloons and poker joints, and they

all got plumb fat and

prosperous as soon as our bunch hit town."

After the boys had been relieved of their pay by the "ladies" and the saloons, but whilst they were

still in a good mood, the boys decided to saddle up one of the meanest longhorn steers in the herd and

ride it down the street. One black cowboy named Sam was elected for the ride. Down the street the longhorn

and Sam rode until the steer glimpsed his reflection in the clothing store window. That was all it

took. Seeing a rival, the steer charged. Through the window, down one aisle, back another, and out the now

glassless window the steer charged, Sam hanging on for dear life and the steer's horns bedecked with gentlemen's

attire.

But the incident was not the only time that the citizenry were treated to such activities on a main thoroughfare.

In 1873, 16th Street was used by some cowboys as the location for some bronco busting. The editor of the

Daily Leader deplored the activity because it was

cruel to the animals.

Cheyenne Photos continued on next page.

|