|

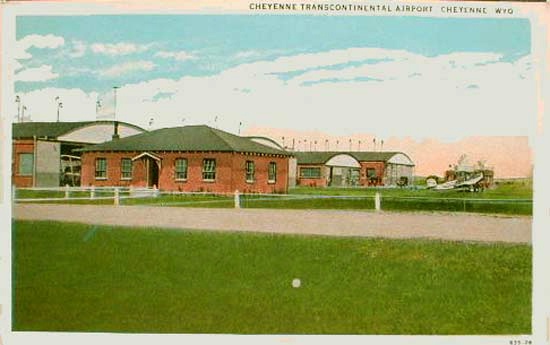

Cheyenne Transcontinental Airport, 1930's

In the 1930's, the Cheyenne Transcontinental Airport was the busiest airport in

the country. Some of the buildings in the view were designed by Cheyenne architect, Frederic Porter, Sr., designer of the

Boyd Building. The art deco terra cotta fountain in front of the terminal building was constructed by

United Airlines in 1934 in memory of early aviation pioneers.

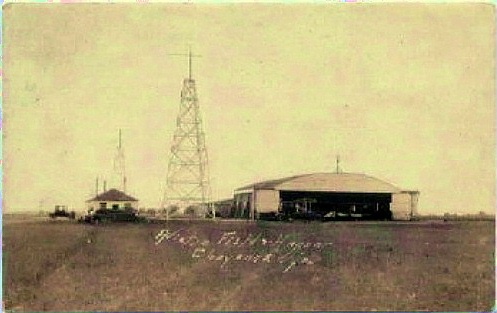

Radio Beacons and Hanger, Cheyenne Transcontinental Airport, 1920's

In 1920, the post office department commenced the long distance carriage of mail by air. Because airplanes of the era were generally limited to achieving an altitude of 9,000 to 10,000 feet, airplanes

going to and from California were fairly well limited to following the same routes as those followed by the

Overland Trail and the Union Pacific Railroad. The limited range of aircraft also required division stations to be established in the

same manner as that followed earlier by the Overland Stage and the railroad. At the division points, the planes could be

refueled and serviced. With establishment of the first airmail routes, Cheyenne was established as the division point between Salt Lake City and

Omaha on the Chicago to San Francisco run. Air service commenced in 1920.

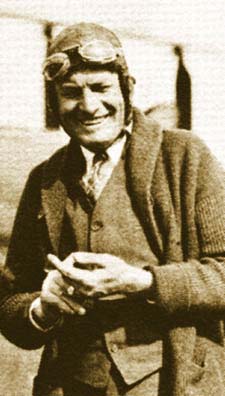

Slim Lewis

Early pilots were guided by visual landmarks observed by leaning out of the cockpit. This gave rise to an

early nickname for a pilot, "Breezo." An early pilot assigned to the Cheyenne Station, Harold T. "Slim" Lewis, commented,

"An instrument panel is just something to clutter up the cockpit and distract your attention from the railroad or riverbed you're following."

In Cheyenne, the principal landmarks for finding the airport were the golden dome of the State House and the

barracks at Ft. D. A. Russell. In 1921, the Post Office published its

PILOTS' DIRECTIONS NEW YORK-SAN FRANCISCO ROUTE.

DISTANCES, LANDMARKS, COMPASS COURSE, EMERGENCY AND REGULAR LANDING FIELDS, WITH SERVICE AND

COMMUNICATION FACILITIES AT PRINCIPAL POINTS ON ROUTE by which the pilots followed the established aerial

route across Wyoming. From Cheyenne two routes were established, a shorter simpler route and one described in the

Directions as Slim Lewis

Early pilots were guided by visual landmarks observed by leaning out of the cockpit. This gave rise to an

early nickname for a pilot, "Breezo." An early pilot assigned to the Cheyenne Station, Harold T. "Slim" Lewis, commented,

"An instrument panel is just something to clutter up the cockpit and distract your attention from the railroad or riverbed you're following."

In Cheyenne, the principal landmarks for finding the airport were the golden dome of the State House and the

barracks at Ft. D. A. Russell. In 1921, the Post Office published its

PILOTS' DIRECTIONS NEW YORK-SAN FRANCISCO ROUTE.

DISTANCES, LANDMARKS, COMPASS COURSE, EMERGENCY AND REGULAR LANDING FIELDS, WITH SERVICE AND

COMMUNICATION FACILITIES AT PRINCIPAL POINTS ON ROUTE by which the pilots followed the established aerial

route across Wyoming. From Cheyenne two routes were established, a shorter simpler route and one described in the

Directions as "about 10 miles farther than the route described previously.

The country over this course is better suited for forced landings, and in case of a forced

landing the pilot is nearer human habitation."

The need for a place to set the plane down upon a forced landing was real. Slim Lewis on one flight from Scotts Bluff to

Cheyenne was forced down four times due to an icing carburetor. After the fourth landing, the last leg of the journey was completed with a

borrowed horse and wagon. The need for emergency fields was recognized. Thus, the Directions noted of

Laramie, "Laramie.-Is the largest town in the valley. Landing fields abound throughout the valley." The absence of sage brush was

an advantage in Wamsutter. The Directions noted: "On the Union Pacific. Fairly good fields

are found between Rawlins and a point 60 miles west. Fields safe to land in show up on

account of the absence of sage brush. The course leaves the railroad where the Union

Pacific tracks loop to the southeast."

At first, there were no night flights. In 1923, the government began construction of illuminated beacons every

twenty miles. Thus, in 1924 Slim Lewis brought in the first night airmail into Cheyenne.

Beginning in 1925, contracts were let, much in the same manner as previously done with stage lines, to private contractors

for the carriage of the mail. In 1927, the San Francisco - Chicago route was awarded to Boeing Air Transport, Inc., a predecessor of today's

United Airlines. At first, the fledgling airline used Boeing Model 40 aircraft which, in addition to the mail, had

room for two passengers. [Writer's comment: Things have not necessarily changed. Some fifty years later, the writer was a passenger

in a mail plane. The plane had room for two paying passengers in the tail. Between the passenger seats and

the pilot and co-pilot was a large pile of mail sacks.]

Early airmail pilot Ham Lee Early airmail pilot Ham Lee

Not withstanding that the two passengers of the Boeing Model 40 were in an enclosed cabin with leather seating, the pilot was still in

an open air flight deck above and to the aft of the two passengers. The enclosed cabin had windows which provided a clear view of

the countryside overwhich the machine flew. The wife of Waldo C. Johnson about 1927 flew from

New York to California changing planes in Chicago and Omaha. She therefore became one of the first women to cross the continent in an

aerolane. On the Chicago to Omaha leg of the journey, the pilot was E. Hamilton "Ham" Lee (1892-1994). Mrs. Johnson later wrote that she

was concerned about the pilot:

"The poor pilot had no protection at all and in bad weather it must be realy frightfully cold. It is a

very unsociable way to travel, for you can have no communication at all with your pilot except when you land, but I would

certainly have been frozen in an open plane, for with my windows closed I was almost cold in spite of a seater, a leather coat Ms. Houghton's sheepskin coat, and the

lumbermen's felt boots which I pulled on over my own high ones. * * * I asked Mr. Lee if he wasn't very cold, but he said he had been warned

of a cold wave and had on his furlined flying suit."

From Cheyenne to Salt Lake City, the plane piloted by Halson A. "Colly" Collison encountered severe headwinds. Collison had previously set the

record from Cheyenne to Salt Lake City of two hours twenty-five minutes.

Mrs. Johnson's flight took seven hours. Mrs. Johnson

noted that with bad wind they could not land at Rock Springs and they

had to refuel at emergency stations, one this side, one the other side of Rock Springs. The gasoline was stored in

barrels. "They fil five gallon cans from these," she wrote, "and then haul them up on the ship. It takes half

an hour this way. In the real landing fields, they have overhead hose and they refuel the ship in a

few minutes.' Collison continued to fly for Boeing and later its successor United Airlines. In the early morning hours of

October 7, 1935, United Airlines Flight 4 piloted by Collison was expected in Cheyenne. A routine signal was received from the

the aircraft indicating that the plane was over Silver Crown. Everything was normal. The Cheyenne

radio room responded by giving wind directions and indicated that in landing the plane was to use caution as there was a west-bound plane in Cheyenne.

Flight 4 did not acknowledge. The wreckage was found three miles east of Silver Crown about 10 miles west of Cheyenne on the John Bell

Ranch. There were no survivors.

Nevertheless by the late 1920's, it soon became apparent that there was a demand for passenger service. Boeing then

developed for the run the 12 passenger Wright powered Model 80. This was soon followed by the more powerful and larger

Model 80A on the transcontinental run. The Model 80A constructed of metal spars with an

exterior skin of fabric, was, for the time, humongous with a wing span of 80 feet and a length of over 56 feet.

The plane could carry its 18 passengers in luxurious comfort cruising at 125 miles per hour.

The principal overhaul center for the Model 80A was established in Cheyenne. Thus, Cheyenne became

one of the main centers for air travel in the United States serving passengers flying across the continent, but also serving passengers and

mail running from Montana south to Denver and Pueblo.

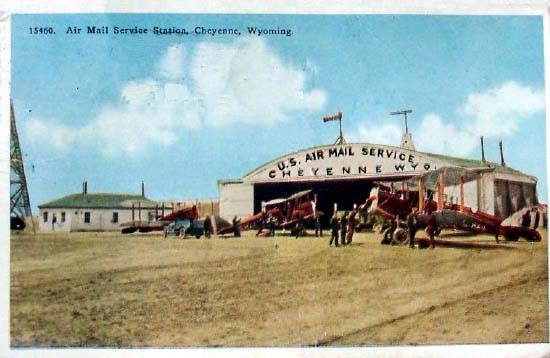

Airmail Planes, Cheyenne Transcontinental Airport, 1927

The Model 80A aircraft, was the height of modern design. A tri-motored biplane, it had an enclosed cabin for the passengers. The cabin, equipped

with leather covered reclining seats and a watercloset with hot and cold running water, was five feet wide. The rows of seats were divided with one seat

on the port side of the craft and two on the starboard side. Each seat had a seperate reading lamp and air vent. The

roar of the three 525-horsepower Pratt & Whitney Hornet radial engines was muffled by sound proofing in the exterior fabric covered cabin walls, permitting passengers

to speak to one another in almost conversational tones. A radio aerial above the cabin assured passengers that the craft was

in touch with a line of radio beacons crossing Wyoming. Other beacons were

established across the state to guide the planes to emergency airmail fields along the way.

Arriving in Cheyenne for Frontier Days, 1930

The aircraf is a Boeing Model 80A. The use of an enclosed cabin for passengers was not an innovation. As early as 1920, the British-operated Imperial

Airways was using tri-motored DeHavilands with an enclosed cabin to connect the European continent to

Britain and in the late 1920's used such craft to carry the Royal Mail and passengers from

Britain to India. The flight to India took a week but was a savings over the three week passage by ship. The major

innovation, however, of the Model 80's was the introduction of two new features, an enclosed flight deck for

the captain and co-pilot and an onboard registered nurse to attend to the needs of the passengers. On previous aircraft such as the

DeHavilands, the flight deck from which the captain and co-pilot guided the aircraft was outside above the cabin and open to the

elements. Prior to the employment of the registered nurses, it was the duty of the co-pilot to attend to the

needs of the passengers.

Collier Trophy.

The Robert J. Collier Trophy was established in 1911 and is awarded for significant advances in aviation. The United States

Air Mail Service won the award in 1922 for safety and 1923 for the introduction of night service. The Air Mail Service carried the

trophy to cities along the transcontinental route and put it on display.

Airmail

stamp, 1927 Airmail

stamp, 1927

The transcontinental flights represented a major savings of time. The Model 80A was, in essence, the Concorde SST of the day. The flight from Chicago to San Francisco took only 20 hours with

stops in Omaha, North Platte, Cheyenne, Rock Springs, Salt Lake City, Elko, Reno, and Sacramento. By train, the same trip

took 3 1/2 days. From San Francisco to New York was only a day and a half by air as compared to 5 days by train.

Nevertheless, flights remained subject to the vagracies of the weather. The daughter of soprano Alma Gluck, freelance magazine writer Marcia

Davenport (1903-1996), wrote in an article "Covered Wagon -- 1932," Good Housekeeping, Ocotober 1932, of her flight from

California to New York. Because of a storm, the plane made an unscheduled landing in Parco (present-day Sinclair). She described the

terminal building in which the passenger waited out the storm as a "little wooley-western shack

on the edge of the field." Because of fog, the plane made another

unscheduled landing in Laramie. When the fog finally lifted, the plane made its ascent over

Sherman Hill and descended into Cheyenne 10 hours late. At Omaha, due to the lateness of the plane, the airline's

caterer forgot to service the plane. Thus, from Omaha to Chicago the only refreshments for

the passengers were tomato juice and sweet buns. Miss Davenport noted that on the

airplane the food was furnished as a part of the fare, while on the train food had to be purchased. She continued,

"To be sure, you get your food regularly, and of luxurious variety, on the railroad; in the air -- you wait and see?"

Cheyenne Transcontinental Airport, approx. 1930's.

Following World War II, equipment improved. The DC 4 was capable of flying non-stop from Chicago to California at 18,000 feet.

Thus, Cheyenne was by-passed. United pulled out. Western Airlines discontinued service on the north-south route. Thus,

today what was once the nation's busiest airport is but a way station for commuter airlines, leading to the rumor

that if one dies and goes to Heaven, one will have to change flights in Denver.

Music this page, courtsy Horse Creek Cowboy:

"Come Josephine In My Flying Machine"

Lyrics by Alfred Bryan

Music by Fred Fisher, 1910

Oh, say! Let us fly, dear

Where, kid?

To the sky dear

Oh, you flying machine!

Jump in Miss Josephine

Ship Ahoy!

Oh, joy! What a feeling

Feels cold, thru the ceiling. Ho, high!

Hoopla, we fly! To the sky so high

(Chorus)

Come Josephine, in my flying machine

Going up, she goes! Up she goes!

Balance yourself like a bird on a beam

In the air she goes; there she goes!

Up, up, a little bit higher.

Oh, my! The moon is on fire.

Come, Josephine in my flying machine

Going up, all on, "Goodbye"

(Repeat Chorus)

One, two, now we're off, dear.

Oh, you, pretty soft, dear.

Whoa! Say! Don't hit the moon.

Oh, no, not yet but soon. You for me,

Oh, gee! You're a fly kid.

Not me, I'm a sky kid.

Gee! I'm up in the air about you for fair

(Repeat Chorus)

Next page, Frontier Days.

|