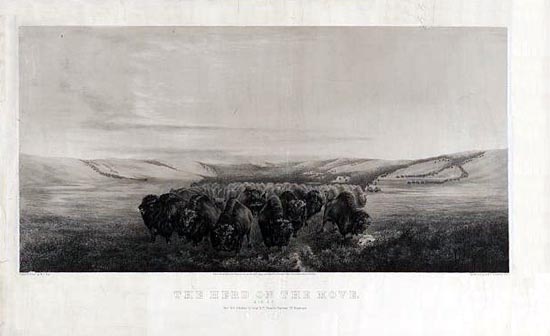

Herd on the Move, W. J. Hays, 1862

At the time of the mountain men, the Indians upon the great plains were dependent upon the

bison and the horse. But scarely a hundred years before, when the first white men

ventured into the northern Rocky Mountain West, not all tribes had horses. Thus, in 1731, when

Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye (1685-1749), began his expeditions in search of

a route across the continent to the Pacific, the Indians had no horses. Thirteen years later, when his two sons,

François and Louis-Joseph de la Verendrye, continued their father's quest, horses amongst the

Indians they encountered appeared to be common. The two sons were the first

white men to venture into present day Wyoming, reaching an area near present-day Sheridan in

January 1743. The expedition, however, could not proceed when it lost its Indian guides.

François explained:

We continued our march until the 8th of January. On the 9th we left the village, and I left my brother behind to guard our

baggage which was in the lodge of the Bow chief. Most of the people were on horseback marching in good order.

Finally on the twelfth day we arrived at the mountains. For the most part

they are well wooded with timber of every kind and appear very high.

Being near the main village of the Gens du Serpent our scouts came to inform us that they had all made their

escape with great precipitation, and that they had abadoned their lodges and a large part of their

effects. this report caused terror among all our people, for they feared that the

enemy, having discovered them, had made for their villages and would get there before they could.

The chief of the Gens de l'Arc did what he could to get that idea out of their

heads and persuade them to go forward, but no one would listen to him. "It is

very annoying," he said to me, "that I have brought you so far and that we

cannot go any farther."

I was greatly mortified not to be able to climb the mountains as I had wished. We then decided to return.

Journal of the Expedition of the Chevalier de La Vérendrye and One of His

Brothers to Reach the Western Sea, Addressed to M. the Marquis de Beauharnois, 1742-43

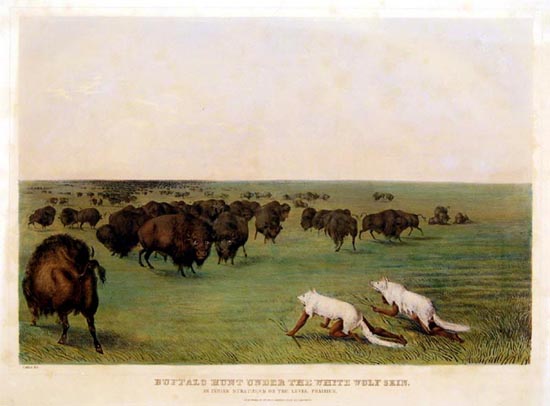

Buffalo Hunt Under the White Wolf Skin, George Catlin, 1844.

In the above painting, the Indians, disquised as white wolves, are creeping up on the bison.

Catlin (1796-1872) toured the American West five times beginning in 1830. His purpose was to document scenes that

he believed would be shortly gone.

Prior to the coming of the horse, the Indians'

only beast of burden was the domestic dog. Thus, travel was limited, tipis were small and

the transportation of provisions was only that which could be carried by hand or on small travois pulled

by dogs. The Indians were, thus, confined mainly to the periphery of the Great Plains.

Game and bison were only those caught by braves on foot. Bison could be killed by sneaking up on the

animals in disquise, by surrounding a small number of the beasts, or by stampeding a herd from a precipice, a method later

to be referred as a "buffalo jump." Edward S. Curtis described the method used:

The earliest method of killing buffalo was by making camp around the herd,

with the tipis pitched close together, side by side; then two young men

with waka bows and arrows ran around the entrapped animals, singing

medicine-songs to bring them under a spell, so that the people could close

in and kill large numbers. Following this primitive method, they slaughtered

numberless bison by driving them into a compound -- a stockade-like

enclosure, usually of logs, at the foot of some abrupt or sheer depression,

its plan of construction depending on the nature of the ground. In a

mountainous region, where the buffalo plains might end at a high cliff, no

enclosure was needed. The long line of stampeded animals would flow over

the precipice like a stream of water, to be crushed to death in their fall.

There was no possibility of drawing back at the brink; the solid mass was

irresitibly forced on by its own momentum, and the slaughter ended only

with the passing of the last animal that had been decoyed or driven into

the stampede. At other times the embankment over which the buffalo ran was

only high enough to form one side of the enclosure. In rare instances pens

were built on the open prairie, and at one side of the stockade was thrown

up an inclined approach along with the buffalo were driven to fall at its

end into the corral.

The most famous of Wyoming's buffalo jumps is the Vore Buffalo Jump located near Beulah. From the layers of

bones, scientists have estimated that some 20,000 bison were killed at the site and that it was

in use as late as 1800 A.D. Other buffalo jumps have been located near Sheridan, the Big Goose Jump,

used about 1500 A.D.; the Glenrock Jump and one on Steamboat Mountain in the Red Desert.

Buffalo Jump

Curtis continues:

The manner of driving and decoying the bison was a varied as the form of

the slaughter-pen; but whatever the method, the purpose and results were

the same -- the object was to stampede the herd, or a part of it, and to

direct the rapidly moving animals to a given point, the Indians knowing

that, once well in motion, they would run into their own destruction. The

Sioux built out in rapidly diverging lines from the pen a light brush

construction, not in truth a fence, as it was only substantial enough to

form a line. Men concealed themselves behind this brush, and when the herd

was well inside the lines the hunters rose up and by shouting and waving

their blankets frightened the animals on. Sometimes a man skilful in the

ways of the bison would disguise himself in one of their skins and act as

leader of the drove to the extent of starting them in their mad rush. By

this method the Indians simply took advantage of a characteristic habit of

the buffalo -- to follow their leader blindly. The movement grew into a

stampede, and forced the leading animals before it. If the advance was

toward a sharp gully, it was soon filled with carcasses over which the

stream of animals passed; if toward swampy land or a river with quicksand

bed, numbers were swalllowed in the treacherous depths. If it happened that

the route took the herd across a frozen lake or stream, the ice might

collapse with their combined weight and drown hundreds; and the Indians

relate many instances in which during winter the herd failed to see the

edge of an arroyo or a small cañon filled with drifted snow and were

buried one after another in its depths, the buffalo seemingly not having

sufficient instinct of self-preservation to stop or turn aside.

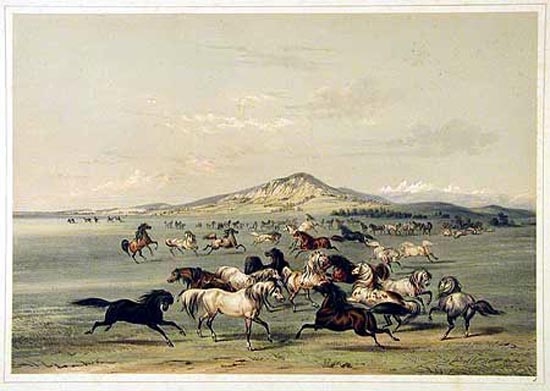

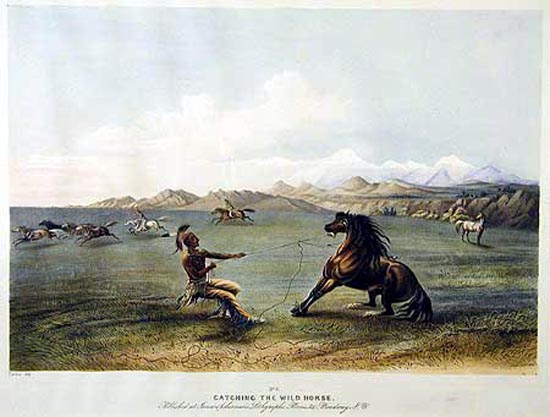

Wild Horses, George Catlin

The coming of the horse to the Great Plains was as a result of the Indians driving

the Spanish out of New Mexico at the time of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. The Revolt was

one of only three times, that the Indians successfully drove (albeit temporarily) white men

out of an area. See Note below.

The Spanish in the conquest of the Aztec Empire utilized horses, an animal which to the

Indians must have seemed terrifying. In the years following the defeat of the

Aztecs, the Spanish moved northward in their quest for gold and the salvation of the souls of

the Indians. In 1598, Juan de Oñate had established the mission pueblo of San Juan along

the Rio Grande River in present day New Mexico. In New Mexico, ranchos were established on which

the Spanish bred horses. The Indians who worked on the ranchos were, however, forbidden

to own horses. Conflicts arose between the military and the Church in the

administration of the new territory. Under the Spanish bureauacracy, canon law was supreme and military administration

was subordinate. The method of converting the Indians to Chirstianity and the forced abandonment of the

old gods was often at the end of a whip. For eighty-two years, the Indians in

New Mexico endured what was, in essence, slavery. They were forced to toil in the fields for the

benefit of the Spanish, to construct the mission churches, abandon their religion and adopt Christian names. In 1675, the Spanish

governor seized 47 of the Indian medicine men. In Sante Fe, the Indians were publicly whipped, three were

hanged, and one committed suicide. One of the Indian medicine

men who tasted the end of the Spanish lash was Juan de Popé. Under threat of a revolution by the

Inidans, the governor released the remaining 43 medicine men including Popé. Popé returned to the

pueblo of Taos. There, he received a revalation from the god Poheyemo that he was to lead his

people against the Spanish.

Supplies to the Spanish colonies in New Mexico came by wagon from old Mexico but once every three years.

The scheduled supply wagon train was for 1680. Knowing that the Spanish were low on supplies

pending the arrival of the train, Popé quietly spread word amongst the different pueblos for a simultaneous

uprising.

On August 10, the Pueblo Indians arose and took control of all pueblos except Isleta. There, the Lieutenant

Governor Alonso Garcia was beseiged. In Sante Fe, Governor and Captain-General, Don Antonio de Otermin, recieved

word of the uprising and the killing of priests and the alcalde mayors of other towns. And even before

orders could be relayed, the captain-general, on his way to mass, received news of yet more deaths of priests, governmental

officials, ranchers, and messengers and their escorts. Refugees informed of Otermin of the burning of the

convents and churches. Soon the governor found himself

under seige in the governmental houses. The Indians gave Otermin a choice, to go in peace or death. The governor made

no response. The Indians dammed off the stream which provided water to the plaza in front of the governor's

palace. In Isleta, Lt. Governor Garcia, believing the captain-general to be dead, began a retreat to

El Paso del Rio del Norte, present-day Juárez City. With no relief from

the Lt. Governor and thrice wounded, Otermin fought on. But without water or other supplies, the Governor found it necessary to

abandon Sante Fe. The Indians

watched without attacking as he retreated all the way to El Paso del Rio del Norte. The Indians burned the ranchos, the churches, and convents.

The holy objects within the churches were defiled. Christian names were banned. Spanish crops such as

barley and wheat were destroyed, to be replaced by the traditional maize and beans. The bodies of the dead priests

were dumped in garbage pits or in front of the doors of their churches. Yet there one thing the Indians did not destroy,

the herds of Spanish horses. Thus, the Pueblo Indians continued the

breeding of horses, trading them to the Utes and the Commanches. In turn, horses were adopted by the Cheyenne, the

Araphaho, the Crow, the Sioux, and the Shoshoni.

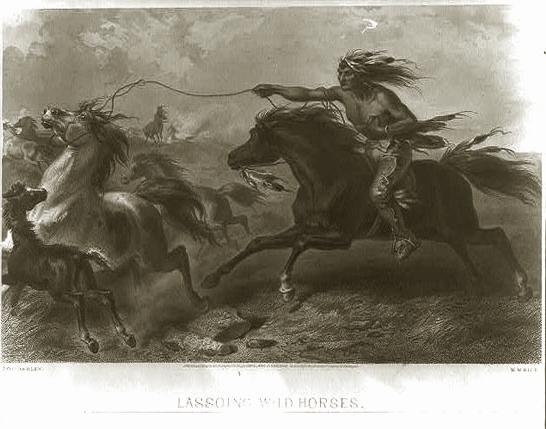

Lassoing Wild Horses, F. O. C. Darley.

By about 1740, horses reached present-day Wyoming. Today, descendents of those horses

wander the Red Desert, the Prior Mountains, and, until recently, between Meeteetse and Cody. DNA testing has confirmed that those

mustangs are almost pure-blooded Spanish horses descended from those captured at the time of the

Pueblo Revolt.

Wild Horses, George Catlin

Next page: The Buffalo Hunters.

|