Wind River Mountains, 1860, Albert Bierstadt

Lander Stage, July 1906

Photo is of the last stage from Rawlins before service was discontinued with the advent of railroad passenger service from Casper to Shoshoni. The stage station was constructed in 1895 by George W. Scott who maintained a photgraphy studio next door. The caption on the photo indicates that this is the stage spoken of in The Virginian. Scant mention of stages is made in Wister's novel. The longest mention is of Molly's 30 hour ride from Rock Creek during which the second driver had imbibed too much and managed to overturn the stage whilst fording a creek. Mention is also made of a "kid" stage driver from Point of Rocks and note is made that the Bishop arrived by stage.

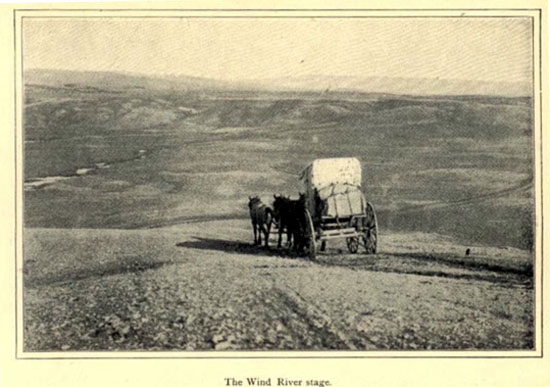

Lander Stage, Scribner's Magazine, 1904

Voss Stage Station Fremont County, 1903. Photo by J. E. Stimson.

At the stage office we were informed that all the places for the night were engaged. Unwilling to lose a day we succeeded in securing a buckboard as an adjunct to the regular stage and started off shortly before midnight on our ride of 160 miles to the wind River. The night was glorious, the stars brilliant and the moon full of splendor. The regular stage preceded us, going ahead with four horses at a sharp gallop. As we drove across the sage-covered prairie the moon went down and the air became pierceing cold. At intervals we stopped to change horses, and at four we halted at a wretched cabin where we breakfasted. From time to time we passed long wagon trains, composed of three wagons fastened together and drawn by mules, carrying freight to the fort or wool to the railroad. Great bales of newly-shorn wool lay in piles by the wayside, and now and again we would hear the tinkle of sheep-bells and pass through large flocks of sheep, the young lambs running by the side of the ewes, while the herder with his dogs kept watch on the ourskirt of the flock.

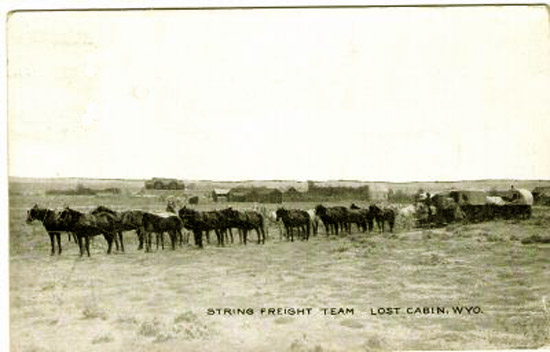

Freight train near Lost Cabin, 1910

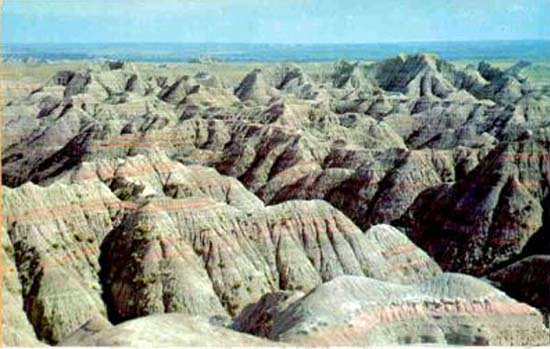

Mr. Culin was actually referring to "Hell's Half Acre" about 36 miles west of Casper.The long twilight seemed to be almost followed by an intimation of the dawn, and we welcomed the sunrise which brought relief from the intense cold. The country became more and more diversified. Ascending a hill just at daybreak we came upon one of the great natural wonders of the region, a vast ravine filled with fantastically carved pinnacles of many-colored clay. This phenonomenon is locally known as the "Devil's Half Acre."

Hell's Half Acre.

As the day advanced the sun's heat became intense, and the impalpable dust from the alkali plain most oppressive. Before noon we met a large coach coming from Lander. Horses were changed, we joined the occupants of the first coach, the entire company proceeding together. The place-names in this region are most suggestive. I could not fail to be interested in my fellow passengers who were bound for Lost Cabin. the drivers, too, were interesting, bright, alert young fellows, all wearing sixshooters strapped in a belt filled with cartidges. These weapons, one is told, are more for ornament than practical purposes. The stages were utterly dilapidated and creaked and groaned unceasingly as they rattled over the stones and deep ruts in the road. We passed the half-way point oppressed with the heat and utterly worn out with the sleepless night ride. The road now travered long ranges of mesa covered with grease-wood and sage-brush. No animal life was visible save little ground birds and an occasional sage-hen that ran, frightened, into the low brush. At sunset the cold again became intesnse and a piercing, icy wind from the distant snow-covered mountains chilled us through and through. we drew the miserable robes about us and tried to keep warm. Unterly worn out with fatigue we would doze off, to be awakened with a start as a jolt of the stage would thrown us forward, aching in each joint and muscle. Shortly after midnight we passed the Arapaho sub-agency and at four o'clock in the morning arrived in Lander.

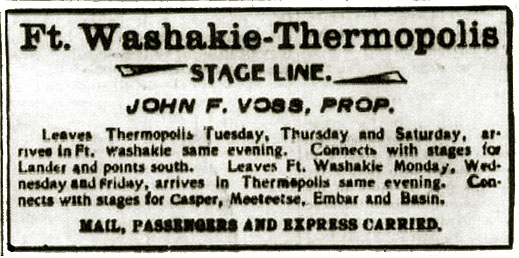

Advertisement for Voss Stage Express, 1905

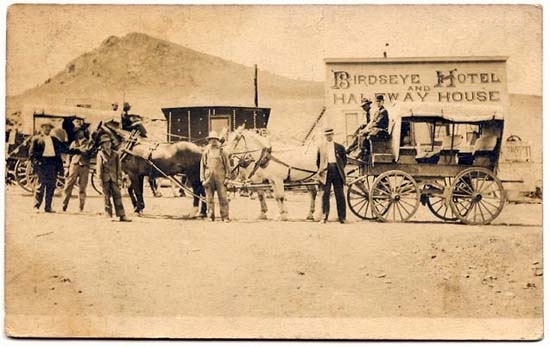

Halfway House Hotel, Birdseye Station, Owl Creek Mountains, approx. 1908

Halfway House Hotel, Birdseye Station, approx. 1908

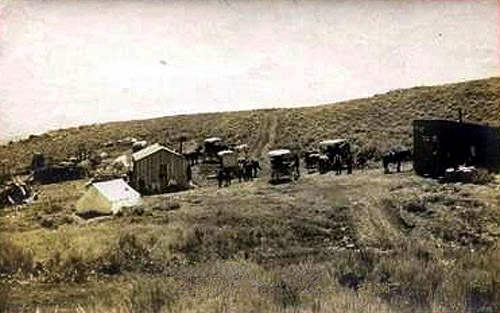

Birdseye Station, undated.

As was noted by Julian Ralph in 1893 (for biographical information see Cheyenne), prior to the coming of the railroads stage transportation was the only means of transportation:

"Excepting Idaho, it is the newest of the States in point of development. It waits upon the railroads to open it up. The Union Pacific Company has done this for the southern part, but until three years ago no other railway entered the State. Even now the other roads merely tap its eastern and northern edges. The Burlington and Missouri Railroad of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy system is pushing its rails into the northeastern part, having come up from Nebraska. It is finished to the Powder River in Sheridan County, and is graded to Sheridan which is a region of rich agricultural promise. This railroad must soon, one would think, push on to the Big Horn country, as we shall see. The Fremont, Elkhorn, and Misouri Valley Railroad, of the Chicago and Northwestern system is also building into the eastern part of the State, and so a beginning is made. But the old-fashioned stage lines are far more numerous than the railroads, and are the sole links between the railways and many interior communities."With the coming of the railroad, the Birdseye Station was abandoned, but it was not until the early 1920's when a road was pushed through the Wind River Canyon that the Birdseye Canyon road itself fell into disuse. Prior to the road's abandonment, it required a degree of intrepedness to attempt the journey in a motor car. In 1920 consideration was being givento the construction of a road which would provide a direct route from Denver to Yellowstone National Park to be known as the the "Yellowstone Highway" To lay out a proposed route two residents of Cody left Cody on May 20 in a new Buick. The pair encountered snow drifts in Birdseye Pass and a truck driver who had been stuck and stranded for two days in the pass. They helped dig him out. He reciprocated by towing the Buick through the roughest parts of the pass. On the way to Casper bridges were almost non-existant and in Natrona County they again became mired down to the top of the rear fenders and had to be rescued by a sheep herder.

Next page: Shoshoni.